Our recent mFarmer projects have reconfirmed the finding that weather forecasts are in high demand from smallholder farmers. However, this type of information is also one of the most challenging to provide.

The accuracy of weather forecasts is an area of significant concern for service providers, as providing wrong information could mislead the farmer, causing them to take actions that may damage their inputs (such as seeds and fertilizer) and crops.

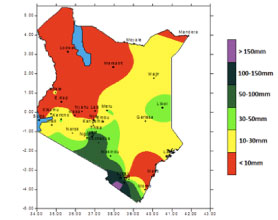

One of the reasons for low accuracy of weather forecasting in developing countries is the lack of metrological stations. Kenya, for example, with a total area of more than 580,00km2, has only 33 met stations operated by the Kenyan Metrological Department (KMD). The KMD records the historical readings of weather conditions at these stations and uses these to develop the official country-wide weather forecast. The geographical spectrum of historical data available is not sufficient to provide relevant and accurate weather predictions for most of Kenya’s rural areas. Still, KMD remains the main source of weather data in the country, partly because it is government sanctioned information.

One of the reasons for low accuracy of weather forecasting in developing countries is the lack of metrological stations. Kenya, for example, with a total area of more than 580,00km2, has only 33 met stations operated by the Kenyan Metrological Department (KMD). The KMD records the historical readings of weather conditions at these stations and uses these to develop the official country-wide weather forecast. The geographical spectrum of historical data available is not sufficient to provide relevant and accurate weather predictions for most of Kenya’s rural areas. Still, KMD remains the main source of weather data in the country, partly because it is government sanctioned information.

At the same time most Sub-Saharan African countries also have privately operated weather stations, as stakeholders reliant on this type of data sometimes find it easier to build their own capacity for collecting and analysing the weather information, than to work with the government.

This approach has been taken by Kilimo Salama, a provider of crop-insurance services via mobile to smallholder farmers in Kenya. Heavily dependent on quality weather data, Kilimo Salama has built 30 metrological stations of their own. Even with the availability of independent weather recordings, the interpretation of the data and actual forecasting is still an issue as it has to be performed by a credible institution.

Another reason for the discrepancies in accuracy of forecasts is the relevancy of a weather forecast to a farmer’s actual location. Where the topographical dimensions of the region are highly diverse, the weather conditions of two locations with a distance as short as 50 km between them could be significantly different.

To provide a relevant forecast to farmers, the service provider should store the information about the exact location of their farm. Although this information is relatively easy to collect by smartphones with GPS functionality, it is difficult to collect on a large scale, as most smallholders own just the most basic mobile phones. In cases where there is an intermediary involved in the service delivery process, geo-tagging could be performed via their handset. For example CKW Uganda uses community knowledge workers who have android devices to geo-locate the users of their service.

The farm location data can also be recorded during the user registration process, easiest to collect if done via a call centre. To find the best possible approximation of a farm’s coordinates, it may be best to use the market centre closest to the farm, or a village that already has recorded GPS coordinates. Offering a choice of weather forecasts for one of the large market centres is another option if other methods of subscription are used such as USSD or paper-form, however this would result in lower relevancy of the forecast provided.

With all the complexities of geo-locating the user, it’s important to note that Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) have the technical capacity to locate each of the network subscribers with a triangulation method, using the information about the location of three base stations closest to the user. The question remains whether MNOs will start using this data to provide relevant information services, agricultural information services in particular, to their subscribers, or continue to keep this information for themselves or maybe using for other location-based services.

With all the complexities of geo-locating the user, it’s important to note that Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) have the technical capacity to locate each of the network subscribers with a triangulation method, using the information about the location of three base stations closest to the user. The question remains whether MNOs will start using this data to provide relevant information services, agricultural information services in particular, to their subscribers, or continue to keep this information for themselves or maybe using for other location-based services.

Given that it is difficult to accurately predict weather beyond a few days at most, it is even more difficult to deliver reliable seasonal weather information to farmers. At the same time, climate change is putting high pressure on the smallholders, as seasons don’t follow the traditional rhythm any longer, making access to weather forecasts even more important for a farmer.

Recent findings show that 5 days is the most reasonable length of a forecast, giving a farmer some opportunity for planning, without compromising the accuracy of the information provided.

There are multiple independent providers of weather forecasts that develop predictions based on comprehensive modeling systems. Among those providing forecasts for Sub-Saharan Africa, there are some that are already working with mobile and radio service providers to deliver forecast information to smallholder farmers, including aWhere, Foreca and IGNITIA.