This blog post was co-written by Arunjay Katakam and Ben Lyon, a board member of Kopo Kopo.

The opportunity of merchant payments in mobile money makes them impossible to ignore. Enabling consumers to pay for goods and services with mobile money increases the utility of a mobile money service, creates an incentive for consumers to store value on their mobile money account, and reduces a mobile money provider’s cash-out commission costs.

But how much should a merchant payment cost, and who should bear that cost? Various pricing models exist, from Safaricom M-PESA’s hybrid model in Kenya to Telesom ZAAD’s free model in Somaliland. With new merchant payment services launching every month, we wanted to start an open conversation around best practices and possible pricing models.

So where should we begin? First, we believe that charging customers is a risky and short-cited play. Here’s why:

- Although mobile money adds convenience, customers are not the primary beneficiaries of a merchant payment – merchants, mobile money providers, and suppliers are, as outlined below.

- Can you remember the last time you paid to make a payment at a merchant? In most markets, any fee over and above the perceived cost of cash (i.e. free) creates a psychological barrier to adoption.

- In the long-term, there is more money to be made by making a mobile money service “top of wallet” and keeping e-money within the ecosystem, than by charging a fee every time a consumer pays a merchant.

Great, but how do I choose the right pricing model?

No single pricing model is right for every market. In fact, no single pricing model is right within a single market.

To choose the best model(s), we recommend running experiments on both sides of the market – with consumers and merchants – and keeping an open mind. In particular, pay attention to short-term and long-term incentives and openly ask: Is there a tension between the two? There may be a short-term incentive to recover deposit commissions (the cost of paying an agent a commission every time a consumer deposits funds into their account), for example, but this may contravene a long-term incentive to expand customer adoption and usage. It is important to identify and confront these tensions upfront.

Here are a few alternative pricing models for mobile money providers to consider for recovering those costs:

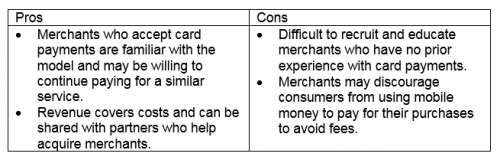

1. Merchant pays

Model & Rationale: Similar to the model employed by the payment card industry, the merchant pays either a percentage, known as merchant discount rate (MDR), a flat fee per transaction, or a monthly subscription in order to accept a mobile money payment from their customer. Given that mobile money providers tend to operate three-party closed-loop ecosystems, the fee should arguably be lower than that charged by the card industry, which uses a four-party model.

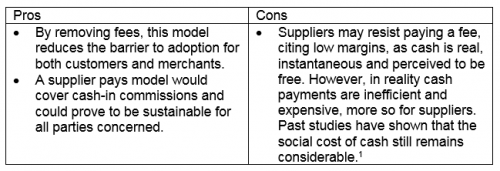

2. Supplier pays

Model & Rationale: Today, when a customer pays a merchant with cash, neither of them pay a tangible fee. Replacing cash with mobile money and without charging either customer or merchant could help drive adoption as it becomes convenient for both, without a financial burden. Further, suppliers arguably have the biggest cash-pain in the entire value chain, simply because they must collect mountains of cash. For these suppliers, costs associated with handling such large amounts of cash are: insurance in transit, salaries for employees to count cash, and theft.

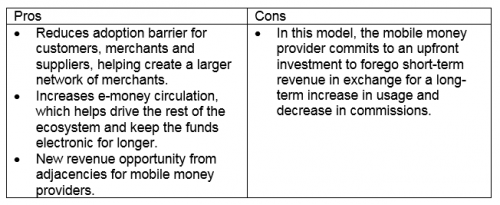

3. Free for All

Model & Rationale: Adoption of merchant payments via mobile money requires a behavior change from everyone in the value chain. Adding a new cost to any actor is likely to have an adverse effect on adoption.

When a customer makes a mobile money payment to a merchant, the e-money stays in the system – rather than being cashed-out. The more this occurs, the better it is for mobile money services looking to build an ecosystem, which allows them to stay relevant in the long-term.

There are two ways in which mobile money service providers could mitigate their costs:

(a) For mobile money services that have integrated with banks, they need to ensure that they have an equal or greater amount of funds coming into their system from bank transfers (as these are deposit commission free funds) than funds paid out to merchants / suppliers in order to mitigate the cost of agent cash-in commissions.

(b) Revenue share from adjacencies, such as interest earned on working capital loans to merchants, could be a sustainable and scalable way to grow merchant payments.

Alternately, a mobile money provider could give merchants a certain number of free transactions every month (e.g. 10-50 free transactions) in order to limit their liability.

This blog post is part of a series on what it takes to scale mobile money merchant payments. In the next post, I’ll discuss the various approaches to customer and merchant user experiences.