Despite a shortage of urban-rural disaggregated data on national identity coverage, evidence from most countries suggests that access to identity is generally highest in more developed urban areas, and lowest in rural locations. Our own on-the-ground research – which now covers Tanzania, Cote D’Ivoire, Pakistan, Nigeria, Rwanda, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Ghana – also shows that geography (urban versus rural) is a critical driver of end-user’s identity-related attitudes, contexts and needs. In Pakistan, for instance, we found that access to formal proof of identity was valued by urbanites as a critical protectionist measure and an enabler of daily mobility, especially for men who navigate police checkpoints as a matter of routine. In rural locations, where community relationships were stronger and formal services were less utilised, the need for identity documents felt less pressing, especially among women. Similarly, the World Bank has noted that in Zambia ‘the urban population is better covered [by national identity], being more dependent on their identity credentials to function in an environment that is moving toward modernity’.

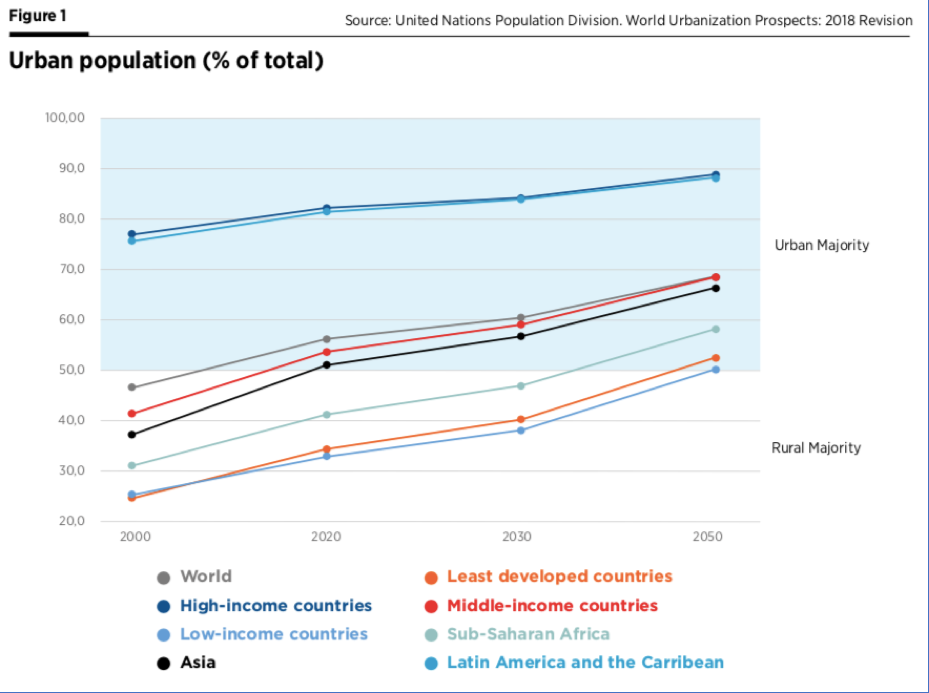

However, for those of us working to provide legal identity for all, including birth registration, by 2030, we ignore the unique identity-related challenges faced by urban dwellers at our own peril. In 2018, more than half (55 per cent) of the global population lived in urban areas, and the United Nations estimates that this will rise to 68 per cent by 2050. While the vast majority of the populations in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa remain rural, rapid urbanisation and population growth in these regions means that they will account for 90 per cent of urban growth over the next 30 years.

The World Bank has highlighted that the urban poor – particularly migrants and unregistered youths – can become digitally, socially and financially excluded in cities where they do not have formal title or registration as a resident, lack official identification documents, or cannot provide a valid proof of address. For this reason, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.9 has set a specific target to provide every person with a legal identity, including birth registration, by 2030. Improving access to identity will also enable the international community to effectively address SDG 11, which aims to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

In our new case study on ‘Identity and the Urban Poor’, we consolidate a wide range of insights on the unique identity challenges faced by three specific types of urban dwellers: children born in urban areas, rural-urban migrants and those who have been forcibly displaced to cities (including internally displaced people and refugees). This high-level case study was developed through a review of external literature, and by looking back at findings from our own end-user research.

While there is no single ‘urban poor’ archetype, we suggest that there are a handful of commonalities shared by those living in urban poverty which will shape the opportunity for mobile-enabled digital identity solutions:

- Lower access to, and usage of, official identity: Official, government-issued identity documents are appreciated by urban residents for their practical value (enabling access to formal services) as well as their symbolic and emotional value (anchoring a person to their identity as a citizen, resident or refugee). MNOs are well-placed to provide national governments and other ecosystem players with the opportunity to leapfrog inefficient, paper- based birth registration systems and offer more inclusive methods of providing unique identities to the underserved.

- Lives marked by instability: The urban poor tend to rely on low-paid, insecure jobs due to skill and educational gaps, or because they lack the identity documents and social networks required to gain access to better employment. They also face particular challenges finding safe and affordable accommodation. Digital identity solutions that enable others to recognise their status as successful business owners and contributors to the local economy would be valuable, as this could facilitate easier access to formal services and improve well-being.

- High access to mobile: Mobile phones play a crucial role in helping migrants and forcibly displaced people (FDPs) establish and maintain important social connections, access vital information, search for jobs, and access services. There is a need to improve how vulnerabilities among urban migrants and FDPs are identified and updated, with the aim of improving how the underserved are targeted and provided with essential services and assistance.

- Importance of social connections: Many migrants leverage social ties in their new urban environments to cope with a multitude of threats and to ensure they are able to access food, accommodation and decent employment. Those who lack these social networks are likely to lack local knowledge and assets, and be less prepared to cope with and avoid the impacts of daily financial, environmental and social hazards. Digital identity solutions that help urban residents establish new forms of connection and support their families ‘back at home’ will be meaningful.

- Impacted by climate change and conflict: Influences such as climate change and prolonged conflict are contributing to global urbanisation trends and disproportionately impacting (rural) youth. Younger and more entrepreneurial individuals are more aware of the growing tension between their local lives and the changes happening around them, and are increasingly looking beyond their local networks for information and advice on where, when and how to migrate. There is an opportunity to leverage a customer’s digital profile to provide more tailored, timely and relevant information and advice, both before and after they migrate to a city.

- Less trusting in government and government services: In many urban areas, poorer residents suffer from overlapping vulnerabilities, such as limited access to government support, discrimination and insecure land tenure – which helps to erode trust in government institutions and reinforce feelings that a legal identity is not needed. To help motivate individuals to access identity or identity-linked services, governments should consider partnering with MNOs, civil society or other ‘known’ institutions that have gained residents’ trust.

The GSMA Digital Identity team is committed to supporting focused research and advocacy efforts, coupled with in-country demonstration projects, to create more enabling environments where the needs of underserved groups are better catered for. This involves advocating for and exploring various unique roles that its mobile network operator members can play in bringing the benefits of digital identity to the poorest and hardest to reach individuals around the world. If you are a GSMA member, policymaker or other organisation seeking to pursue digital identity solutions for the urban poor and other underserved populations, please contact the Digital Identity team at [email protected].