On Wednesday, 29 May, the Mobile for Development Utilities team was pleased to attend the fifth annual Business & Poverty conference at Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University. The conference brought together a range of innovation scholars and practitioners from India, China, Nigeria and beyond to discuss what businesses can do to help address the challenge of global poverty. Given that our Mobile for Development team leverages innovation in digital technology to help achieve the SDGs, we were excited to learn, engage, and share our experiences.

The promise of market-creating innovations targeting non-consumption

In the opening presentation, Efosa Ojomo set the stage by presenting the “theory of change” underlying his recent bestseller, ‘Prosperity Paradox’ (co-authored with innovation and business experts Clayton Christiansen, Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School, and Karen Dillion, contributing editor to Harvard Business Review).

Ojomo’s presentation centred around four key messages:

1. Some well-intentioned anti-poverty programmes are not sustainable

Before studying at Harvard Business School, Ojomo and his friends set up a non-profit organisation, Poverty Stops Here, which aimed to address the challenge of lack of access to water in his home-country, Nigeria. The organisation raised over $300,000 to build wells across five rural communities. Unfortunately, Poverty Stops Here discovered that without a sustainable commercial and long-term maintenance and repair strategy, wells can easily break down. Today, only one in five wells that his organisations had initially installed are still operational.

Similarly, it is well-documented that some well-intentioned global development interventions fail to pay sufficient attention to the role of incentives, and local context, which ultimately undermines their long-term sustainability and can even result in negative-externalities.

Poverty Stops Here’s failure, but also persistently high poverty levels across some developing economies, particularly in Africa (forecasts indicate that by 2030, nearly nine in 10 extremely poor people will live in Sub-Saharan Africa), led Ojomo and his co-authors to focus on the role of innovation in poverty reduction.

2. In struggle lies opportunity – target non-consumption

When making investment decisions, most businesses narrowly focus on the potential of established consumer market segments. For instance, firms might pay international consultants hefty fees to answer questions such as, “How many people are in the middle class in Kenya?” or “How much do the Senegalese spend in supermarkets on a monthly basis?”.

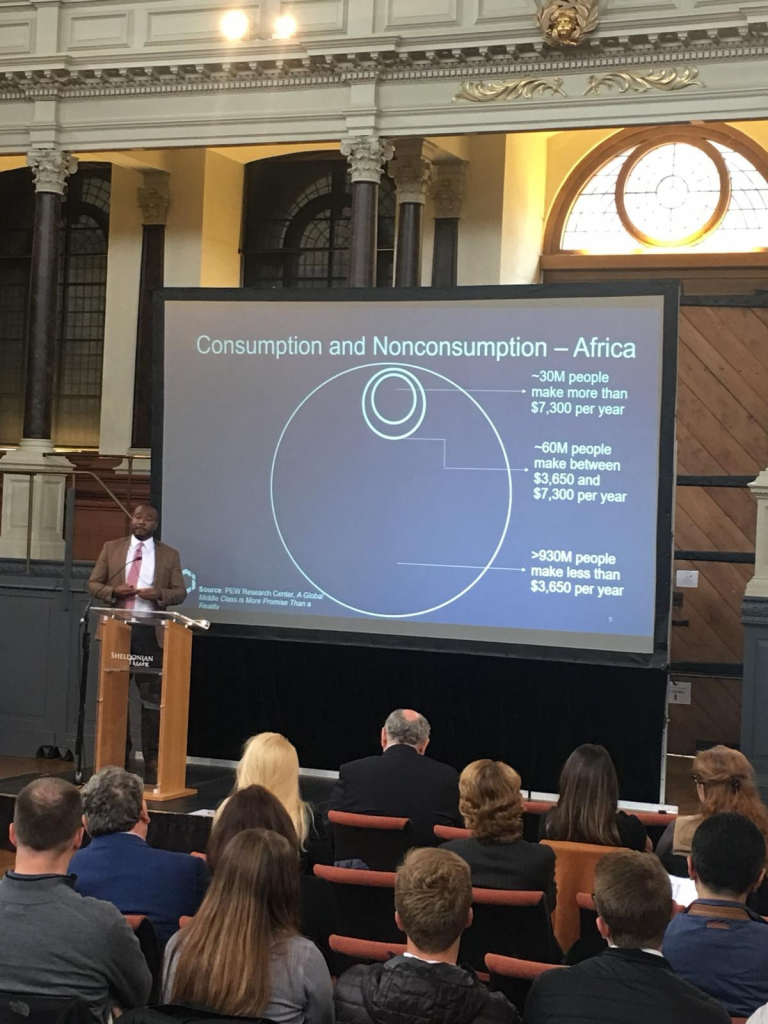

But as Ojomo stressed (see figure below), merely focusing on established upper-tier consumer market segments leaves over 930 million people in Africa out of consideration because they are deemed too poor, too uneducated, or too uninteresting to develop products for. This general disregard by most businesses not only trivialises the struggles of low-income communities, but is also a bad business strategy! (Recommended Read: Cracking Frontier Markets)

Of course, targeting non-consumption differs from targeting established consumer market segments. Fundamentally, it implies an understanding of the daily struggles facing the poor. It also requires the capability to think about innovative ways to overcome the inability of a poor, would-be consumer to purchase (and use) a product or service because it is not affordable or inaccessible to them. This leads to another important observation.

3. Not all innovations are created equal

Ojomo and his co-authors differentiate between different forms of innovations that can have important path dependencies for economy-wide productivity growth:

- Sustaining innovations are improvements to existing solutions on the market and are typically targeted at customers who require better or more differentiated performance from a product or service (Toyota’s ‘Lexus’ series, for instance).

- Efficiency innovations allow companies to do more with fewer resources. They are critical to almost every industry and enable companies to improve profitability and retain customers. While they raise company-wide productivity, many labour-replacing efficiency innovations (such as the automisation of production processes) are not always good for existing employees.

- Market-creating innovations transform complicated and expensive products into ones that are so much more affordable and accessible that many more people are able to buy and use them. For example, Mo Ibrahim’s mobile operator Celtel (now Airtel) made a previously expensive solution – long-distance calls – affordable and accessible to millions of new customers. M-Pesa (mobile money) offers financial services to millions of Africans, who were previously excluded from formal banking. According to the 2018 Mobile Money State of the Industry Report, there are over 395.7 million mobile money accounts collectively accounting for $26.8 billion in transaction value in Sub-Saharan Africa alone. Similarly, our programme’s early support to off-grid solar providers pioneering pay-as-you-go technology (such as M-Kopa, PEG Africa, or Fenix) helped make a previously unaffordable product (Solar-Home-Systems (SHSs)) accessible to low-income communities through an innovative lease-to-own model. Market-creating innovations also have the potential to create good local jobs. For instance, employment across the (off-grid solar) value chain is estimated to rise from 77,000 in 2018 to 350,000 in 2022 in East Africa alone according to a recent report by GOGLA, GIZ, and Vivid Economics. Collectively, market-creating innovations can serve as a foundation for inclusive growth.

Lumos sales agents deliver solar-home-systems in Nigeria

4. Sometimes infrastructures have to be ‘pulled’ by market-creating innovations

Investments into public infrastructures (schools, hospitals, roads, grid connections) are theoretically ‘good’ investments, “but when made without factoring in local context, incentives, and appropriate sequence, they can unintentionally cause more harm than good”, according to Ojomo et al.

As part of the ground-breaking Swachh Bharat Mission, the Indian government committed to eradicating open defecation and offering basic sanitation services to every Indian citizen. The government built more than 10 million toilets in 2014 and 2015 with plans to build an additional 60 million by 2019. Yet as the Indian government quickly realised, successful sanitation interventions have to leverage multiple stakeholders along the entire sanitation value-chain and go beyond the provision of hardware, as we have repeatedly argued.

Though top-down infrastructure provision obviously has an important role to play, it is not always the sufficient or right answer. Market-creating innovations (such as the mobile industry) have the ability to ‘pull-in’ infrastructure and services.

Since the reach of mobile connectivity is greater than the reach of basic utility services, this insight has been key to our programme as well. While, according to GSMA Intelligence, mobile penetration in Sub-Saharan Africa has reached 75 per cent, only 42.8 per cent of SSA’s population has access to electricity, only 24 per cent has access to safely managed water services, and only 28 per cent has access to at least basic sanitation services. By leveraging the reach of mobile services and mobile infrastructure (telecom towers, points of sale, agent networks and so on), our programme has aimed to ‘pull-in’ sustainable and affordable utility service provision for underserved communities with the aim of helping to achieve SDG 6 and 7.

The GSMA Mobile for Development Utilities programme would like to thank the organisers and speakers for this thought-provocative conference.

The GSMA Mobile for Development (M4D) Utilities programme is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), USAID as part of its commitment to Scaling Off-Grid Energy Grand Challenge for Development and supported by the GSMA and its members.