This is part 1 of a guest blog by Chloe Gueguen, former Market Insights Manager, GSMA Connected Women.

Mobile money has shown its potential as a powerful catalyst for financial inclusion, yet, a gender gap persists. Part 1 of this blog looks at a case study from Chad that shows how tapping into traditional group savings behaviours can provide a compelling new use case for digital financial services.

To date, two billion people globally still do not have an account at a formal financial institution, most of whom are women (only 58% of women have an account, compared to 65% of men).[1] Now available in two-thirds of low- and middle-income countries, mobile money has shown its potential as a powerful catalyst for financial inclusion. Yet, a gender gap persists, and women are still 36% less likely to use mobile money than men [2] Previous GSMA Connected Women research such as our recent findings from nearby Mali and Côte d’Ivoire [3] have already highlighted the need to make mobile money products more relevant for women, by ensuring they meet their financial needs. Building on the insights derived from an in-market study commissioned by GSMA Connected Women, this blog looks at how tapping into traditional group savings behaviours can provide a compelling new use case for digital financial services, helping extend women’s financial inclusion in developing countries, such as Chad.

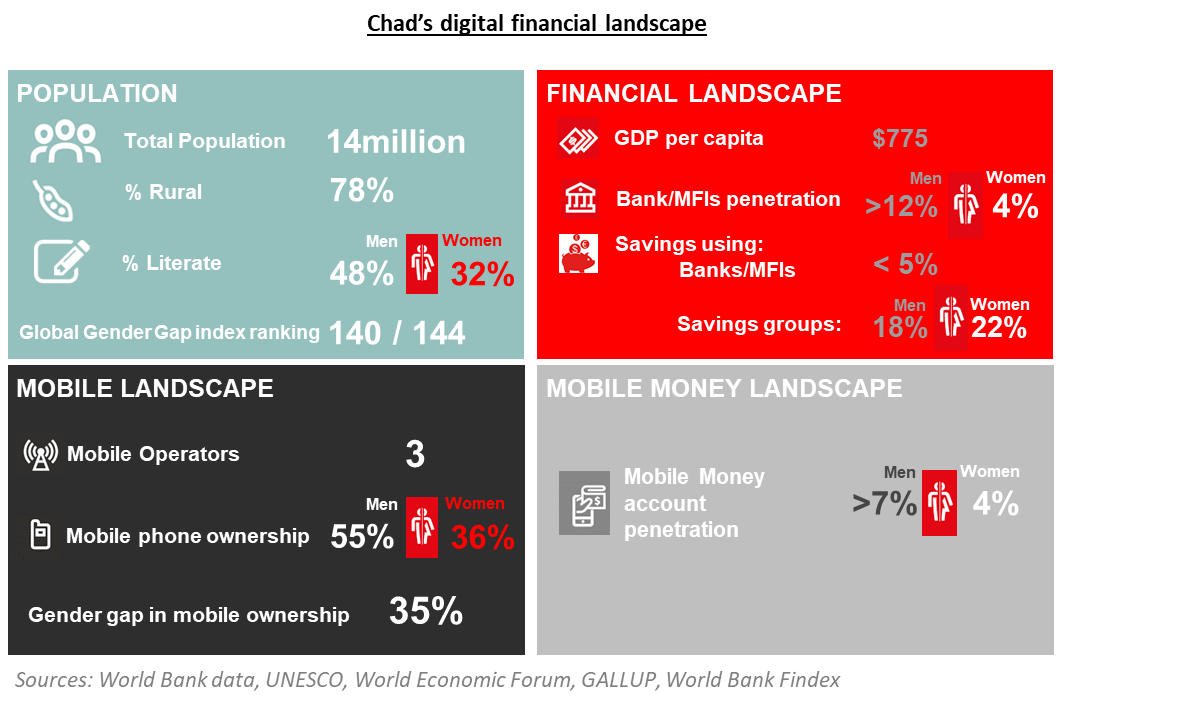

In Chad, only 4% of women (versus 12% of men) have an account at a financial institution and only 4% (versus 7% of men) have a mobile money account, [4] meaning that the vast majority of female Chadians are excluded from financial services that could have life-enhancing benefits not just for themselves but also for their families. Digital financial services can help accelerate financial inclusion for women in Chad, but needs to do so in a relevant way that responds to the needs of the local population.

Savings Groups: an entry point for financial services providers to isolated communities

Savings Groups: an entry point for financial services providers to isolated communities

Savings groups, known as ‘paarés’ in Chad, [5] have been in existence for centuries and remain very popular. There are over 14 million members of savings groups across 75 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, representing a promising platform for financial inclusion in underserved markets. [6] The idea is quite straightforward: in most Chadian paarés, a group of people regularly contribute a fixed or variable amount of money to a collective pot, and members either take their turn to collect the proceeds at the end of a cycle or the savings can be used for a community project (e.g. to build a well). Over one in five Chadian women (22%) [7] claim to have saved using a savings club or person outside of the family (vs. 18% for men), demonstrating that savings groups are particularly important for women. For many, these informal savings mechanisms are their only way to access finance, save money, and realise their dreams and projects. Our research highlights how paarés are more than just ‘savings’ tools: they are also used for informal credit, insurance, and investment. On top of this, paarés are an important part of Chadians’ lives; they are part of the social fabric, offering support and community cohesion.

Source: quotes from GSMA Connected Women consumer research conducted in Chad, in February 2017

Tigo Cash Paaré: A digital innovation to reach women with financial services that really matter to them

In a bid to digitise Chad’s traditional Paares, Tigo Chad launched ‘Tigo Cash Paaré’ in late 2015, a group savings product enabling members to contribute to a group wallet from their mobile phones. This innovative product forms part of Tigo Chad’s strategy to achieve their GSMA Connected Women Commitment [8] to reduce the gender gap in their mobile money customer base, by emulating Chadian women’s existing financial behaviours.

Supporting Tigo Chad in its Commitment toward financial inclusions for women, GSMA Connected Women conducted qualitative research to understand how to optimise Tigo Cash Paaré in order to help accelerate mobile money uptake among women.

The success of Tigo Cash Paaré lies in having identified and overcome the weaknesses of traditional paarés

While traditional informal savings groups provide numerous benefits – including access to finance, flexibility, and supporting community cohesion – they are not without their downsides The cash collected can be stolen or misused, causing safety, trust and transparency issues, as well as additional pressures on the group leader (known as the ‘Kong’ in Chad), who is generally accountable for the group funds’ safety. The cash-based nature of savings groups also means that members are required to physically meet on a regular basis and at an agreed location (often a member’s house) in order to be able to contribute.

Tigo Cash Paaré’s consumer appeal relies on its ability to overcome many weaknesses of traditional paarés. When asked about the strengths of this product, users cited three key elements:

-

- Improved security, given the group’s funds are safely stored on the digital wallet and can no longer be stolen or lost

-

- Increased transparency since it enables members to monitor funds and their contributions at all times

Source: quotes from GSMA Connected Women consumer research conducted in Chad, in February 2017

Source: quotes from GSMA Connected Women consumer research conducted in Chad, in February 2017

Opportunities for Tigo Cash Paaré include building awareness, knowledge and trust in mobile money and reflecting the flexibility of the traditional paarés

Whilst consumer reaction to Tigo Cash Paaré was generally positive, our research identified a number of consumer and business opportunities that could trigger further adoption.

On the consumer-side:

-

- Lack of awareness appeared to be the largest barrier to Tigo Cash Paaré’s uptake and scalability. Above-the-line marketing campaigns (radio and television) had generated limited awareness, and only a handful of respondents had learnt about the product through agents or via word of mouth.

-

- The foundations of Tigo Cash Paaré are Tigo Cash (Tigo’s underlying mobile money platform), and hence, it requires users to have a basic understanding of, and trust in, mobile money. This was not necessarily the case among the target users we spoke to as Chad remains a financially cautious, cash-based society where, for many, mobile money can be hard to grasp, intangible, and less reassuring than physical cash.

-

- Chad is a market with relatively low mobile phone ownership, particularly for women,[9] preventing direct access to Tigo Cash Paaré. Handsets, even the most basic models, can be viewed as unaffordable; and in some communities, women were prohibited to own a mobile phone.

-

- The low levels of literacy [10] and digital literacy, especially among women, meant that some users felt unconfident using Tigo Cash Paaré, which is predominantly SMS-based.

On the business side:

-

- Users regularly referred to distribution challenges, including: network and connectivity issues preventing access to Tigo Cash, issues with agents (availability and their knowledge of the service), and the lack of cash liquidity and e-money float, which was preventing users to cash-into their individual mobile wallet to pay their group contribution.

-

- Product and services issues were mentioned when Tigo Cash Paaré could not replicate the fluidity and flexibility of traditional paarés. Key examples of this include the product’s payment and subscription conditions (which do not allow for late or missed payments, and requests a minimum of 10 users to open a Tigo Cash Paaré wallet)

- User experience was also a barrier for some, namely: the menu was sometimes perceived as complex for first-time mobile money users or the illiterate, and users cited having issues with the responsiveness and knowledge of the Customer Service hotline, as well as needing to memorise a large number of USSD codes.

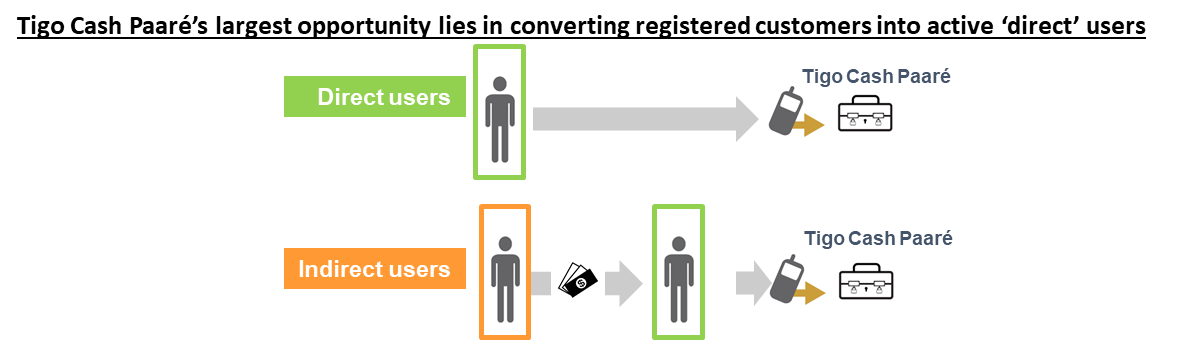

The consequence of these challenges was that, although the product was appealing to most users, the leap from not using mobile money at all to being an active, ‘direct’ Tigo Cash Paaré contributor was too great for many. Once registered to the service, many users appeared to become ‘indirect’ users and relied on the help of another person to contribute on their behalf.

[1] World Bank, Global Findex 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/globalfindex

[2] Using the GSMA definition of the “Mobile money gender gap”, which refers to how less likely a woman is to have a mobile money account: (% of men – % of women)/ % of men. This figures is based on data from World Bank, Global Findex 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/globalfindex

[3]https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development//wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Mapping-the-mobile-money-gender-gap-Insights-from-Cote-d%E2%80%99Ivoire-and-Mali.pdf. Also see the GSMA and the Cherie Blair Foundation for Women report on “Women & Mobile: A Global Opportunity”, 2010 https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development//wp-content/uploads/2013/01/GSMA_Women_and_Mobile-A_Global_Opportunity.pdf and the GSMA report “Unlocking the Potential: Women and Mobile Financial Services in Emerging Markets, 2013 https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/programme/connected-women/unlocking-the-potential

[4] World Bank, Global Findex 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/globalfindex

[5] Also named ‘Chamas’ in East Africa, ‘Tontines’ in West Africa, ‘Gameya’ in the Middle-East, and officially known as ‘Rotating Savings and Credit Associations’(ROSCA).

[6] Delivering Formal Financial Services to Savings Groups: A Handbook for Financial Service Providers, 2017

[7] World Bank, Global Findex 2014, http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/globalfindex

[8] https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/commitment/tigo-chad

[9] According to GALLUP, 36% of the female Chadian population own a mobile phone (vs. 55% for men).

[10] UNESCO (2015), only 32% of the female Chadian population is literate (vs. 48% for men). According to WEF data (2016), Chad is also the country with the highest educational attainment gender gap.

This initiative is currently funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), and supported by the GSMA and its members.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation also supports the GSMA Connected Women programme, funding research to better understand where along the mobile money customer journey women tend to drop off more than men and identify opportunities for addressing key gender gaps in specific markets in Africa.