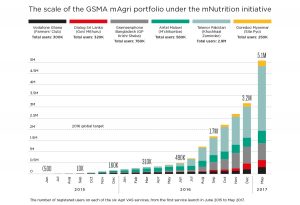

Our most recent publication, “Creating scalable, engaging mobile solutions for agriculture”, is the culmination of three years of work for the mAgri programme. Under the mNutrition Initiative funded by UK aid from the UK government (DFID), we have been working with six mobile network operators (MNOs) to support the launch and scale of agricultural value-added services (Agri VAS). Leveraging findings from user experience (with help from our partners frog design), business intelligence analysis, customer feedback and sharing knowledge with each other, the product teams developed services that cumulatively reached more than five million registered users worldwide.

Those are registered users, but if we dig beneath the vanity metric to see how many users are engaging with the services regularly, we find that 59% of the whole registered user base was active in December 2016, and that two thirds of those were power users – active users who were returning to the service. This represents a ten-fold increase in the number of power users from our last set of projects, the mFarmer initiative. You’ll have to look into the report series to understand what we think contributed to this success in detail, because today I want to focus on the outcomes for end users.

Along with our MNO partners and our monitoring, evaluation and learning partners, ALINe initiative. ALINe, we performed phone surveys and field research to explore the benefits of Agri VAS in all six countries between December 2016 and February 2017. These interim studies, performed between nine and fifteen months after launch, were designed to understand whether and how users were benefitting from services – were they changing the way they farmed? How, and with what effect? We tracked self-reported changes made on users’ farms in areas such as planting, land management, use of chemical inputs, and harvest and storage practices, as well as income and productivity increases.

Users made significantly more changes on their farms than non-users in at least one area for each service, showing the power of mobile services to drive changes in behaviour. Overall, 75% of all power users are estimated to have made on-farm changes – this translates to 1.5 million farmers globally.

In some cases, users are starting to see the benefits of these changes, too – power users in Pakistan are more likely to report increases in income than non-users, and power users in Malawi are more likely to report increases in productivity. One user in Malawi said:

“For the season 2015, I harvested 5 bags of 50 kg each while during the 2016 season I harvested 22 bags. […] The increase was due to the advice I got from the service.”

M’chikumbe user, male, 35, Lilongwe District, Malawi

We’re very excited about the cases where services, which were researched, designed and iterated upon in accordance with human-centred design principles, addressed pressing needs identified by users. For instance, research in Sri Lanka found that farmers there overuse chemical inputs: its consumption of fertiliser in 2014 was 245 kilograms per hectare of arable land, which was 50% higher than in India. The resulting health and environmental hazards, including high incidences of chronic kidney and lung diseases in major rice-growing districts, are recognised by the FAO. Farmers interviewed during design research knew about these hazards, however they had received little instruction on how to reduce the use of such inputs whilst managing their production costs. Power users of Dialog’s Govi Mithuru service in Sri Lanka were more than twice as likely as non-users to report decreasing their dependence on chemical inputs like fertilisers and pesticides.

“Earlier we used lot of fertiliser for the cultivation. I used to apply one bag of fertiliser for my paddy cultivation. But now I apply only half a bag of fertiliser. Listening to those messages, I understood that we are applying excessive amount of fertiliser. We tend to think that the more we use fertiliser, the better it is for the cultivation. But the service helped us to understand the amount of fertiliser required for paddy.”

Govi Mithuru user, male, 52, Pollonnaruwa, Sri Lanka

Want to know more about these successes and how they were achieved? In our report, you’ll find a full account of the processes we advocate during set-up and implementation to create scalable, engaging Agri VAS which impact end-users.”

Access the full report series here

Are you already running an Agri VAS? Then you may be interested in joining our best practices community, the priority learning partners (PLP) initiative. We can help you to use similar metrics to those used in this report to understand the scale and success of your service.

Apply to join the PLP initiative

If you have any other questions, please contact us: [email protected]. To receive the mAgri quarterly newsletter, please sign up here

This project was funded with UK aid from the British people.