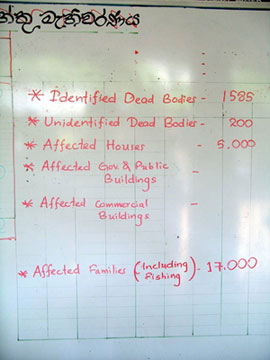

On December 26th 2004, a massive undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, measuring 9.1 on the Richter scale caused a massive tsunami that affected people in fourteen countries. The Indian Ocean Tsunami, as it has become known, was one of the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded causing the deaths of almost 250,000 people, injuring a further 500,000 and displacing almost 2 million. While many parts of the world were celebrating the festive season with family and friends, communities by the Indian Ocean encountered waves with a height of up to 30 metres that left death and destruction in their wake. Local economies were devastated and in many cases communities which hinge on fishing and tourism are still to fully recover. Indonesia suffered the most casualties, followed by Sri Lanka, India and Thailand but the tsunami caused deaths as far away as Kenya and South Africa.

Reports from Sri Lanka at the time indicate that while there was no early warning system there was also an evident lack of knowledge of what a tsunami is. Even after the tsunami had struck there was little awareness in the inland communities of what had happened by the coast. The word tsunami in either Sinhala or Tamil (two native languages) actually meant very little as there had been no prior experience. Most of the 35,000 lives lost in Sri Lanka could have been saved if a simple warning to evacuate coastal areas had been delivered. There was a window of around 90 minutes between the  earthquake and the arrival of the waves on the Lankan East coast – even longer until it hit the Lankan West coast. A warning delivered 90 seconds in advance of the impact would have enabled many people to get to higher ground and make themselves safe.

earthquake and the arrival of the waves on the Lankan East coast – even longer until it hit the Lankan West coast. A warning delivered 90 seconds in advance of the impact would have enabled many people to get to higher ground and make themselves safe.

An English schoolgirl called Tilly Smith holidaying in Thailand with her family became somewhat of an inadvertent media sensation. Tilly noticed the sea change from a flat serene surface to one becoming increasingly foamy and then slowly noticed the rising swell of the sea. Recalling a previous school geography lesson on earthquakes and how they can cause tsunamis, she screamed at her mother to run with the rest of her family. The family acted and fortunately so as minutes later the beach was struck by the wave. The experience of Tilly and her family presents in minute but stark and tangible terms, the importance of both early warning systems and community level involvement. A ten year old school girl raised the alarm in the only way she knew and in doing so saved her community, her family.

For a tsunami warning system to function effectively three things must be in place; rapid evaluation of earthquake magnitude and the corresponding sea level estimations, reliable communication systems and prepared communities. While none of these were in place in 2004, since then massive technical and policy advancements have been made to better enable communities to mitigate against a recurrence. Last month LIRNEAsia – a regional policy and regulation think tank for Asia Pacific – organised a public lecture on Disaster Risk Reduction and regional readiness. This lecture played one part in the Indian Ocean Tenth Annniversary (IOTX) commemorating the 10th year anniversary of the tsunami. Speakers from four different organisations outlined the advancements made and how mobile networks play a crucial role in warning the public – or the last mile of communications as it is known.

Dr. Stuart Weinstein, the assistant director of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre, demonstrated the growth in number and accuracy of real-time data concerning seismic activity and sea-level data collected from monitoring networks in the region. As a result the speed at which scientists can react to such events has increased. Mr. Koichi Katagiri, Director Global ICT Strategy at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan spoke about the use of J Alerts and how the Japanese authorities alert citizens of impending tsunami, earthquakes or volcanoes. While J Alerts uses a loudspeaker system, a complementary system operated by the Japanese Meteorological Agency uses radio, television and mobile phones to alert citizens in a similar fashion. Mr. Michael de Soyza of Dialog spoke of the Disaster and Emergency Warning Network (DEWN) which uses GSM Cell Broadcast technology to transmit alerts through an early warning message. DEWN has been adopted by the Lankan National Disaster Management Centre and remains one of their key tools in alerting the public. DEWN version 2, for smartphones, is being developed at present. Finally, Dr. Vinya Ariyaratne, the General Secretary of Sarvodaya (Sri Lanka’s largest people’s organisation) reported on the growing ability of communities to respond to disaster warnings since educational and awareness programs have been put in place since the tsunami. People are now empowered with knowledge and everyone in the coastal regions of Sri Lanka knows the meaning of the word tsunami.

Using one of the world’s deadliest disasters, this blog post highlights the needs for three things in DRR; data collection, effective message dissemination and prepared communities. Mobile networks can play a role in all three aspects of DRR although the strongest role is in message dissemination as evidenced by the early warning services provided by Dialog Sri Lanka and the Japanese operators.

If a future earthquake causes a similar tsunami in this region, the lessons learned from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, along with the increasing role of mobile networks in disaster preparedness and response, should ensure a much smaller impact on lives and economies.

With thanks to Rohan Samarajiva and Nuwan Waidyanatha from LIRNEAsia for their input and the pictures.