India’s Payments Banks (PBs) regulatory model has garnered a lot of global attention, partly because of its expected potential to tackle financial exclusion. It has also served as an example for countries such as Nigeria, which has developed a similar regulatory model for the licensing of Payment Services Banks (PSBs). In this blog, we try to unbundle the regulatory environment in which Payment Banks operate in India and highlight the challenges and opportunities ahead. For the purpose of this blog, a lot of valuable insights were received from industry stakeholders, opinion leaders, and payments experts who engaged with us and shared their experiences.

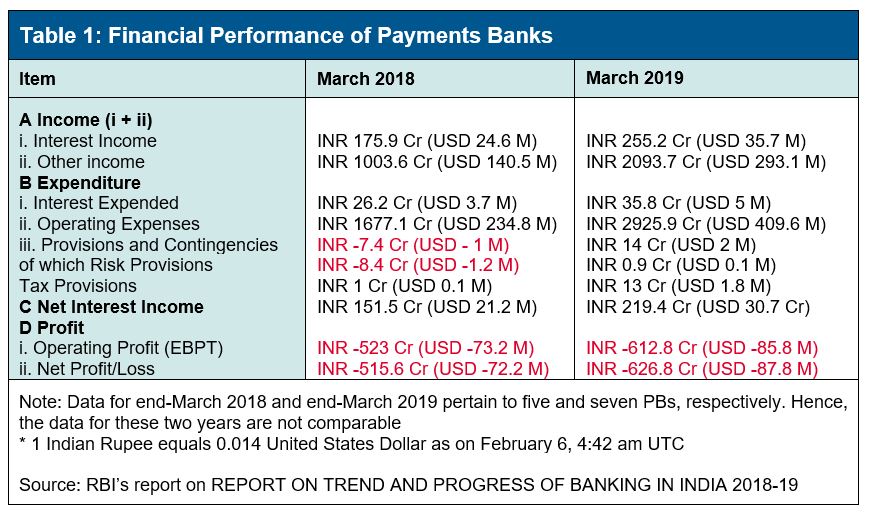

As of today, out of 11 initial licensees, we are left with six active PBs with five of the initial licensees not operational for multiple reasons. Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) recent report on trends and progress of Banking 2018-19 indicated that the operational payments banks showed net losses of INR 626.8 Cr ($87.8 million) for FY19.

PBs were set up based on the recommendations of the RBI Nachiket Mor Committee on Financial Inclusion. The objective was to improve financial inclusion by harnessing technology services via mobile. In November 2014, the RBI issued the Guidelines for Licensing of Small Finance Banks and Payments Banks. Forty-one applications for payments bank licenses were submitted to the RBI, which granted in-principle approval to 11 payments banks in 2015. These new banks were expected to accelerate financial inclusion in India, particularly by offering financial services in unbanked and underbanked regions of the country.

Key licensing requirement for Payments Banks as per RBI’s 2014 guidelines were:

- Minimum capital of INR 100 Cr (USD 14.04 M);

PBs cannot undertake lending activities, and their design is functionally equivalent to that of pre-paid instrument (PPI) providers; - Apart from amounts maintained as Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) with the Reserve Bank on its outside demand and time liabilities, they have to invest minimum 75 per cent of its “demand deposit balances” in Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) eligible government securities/treasury bills with maturity up to one year and hold maximum 25 per cent in current and time/fixed deposits with other scheduled commercial banks for operational purposes and liquidity management;

- PBs cannot accept deposits higher than INR 1 lakh (USD 1403.6) per individual customer;

- Minimum Capital requirement is 15% capital to risk-weighted assets ratio; and

- They cannot issue credit cards.

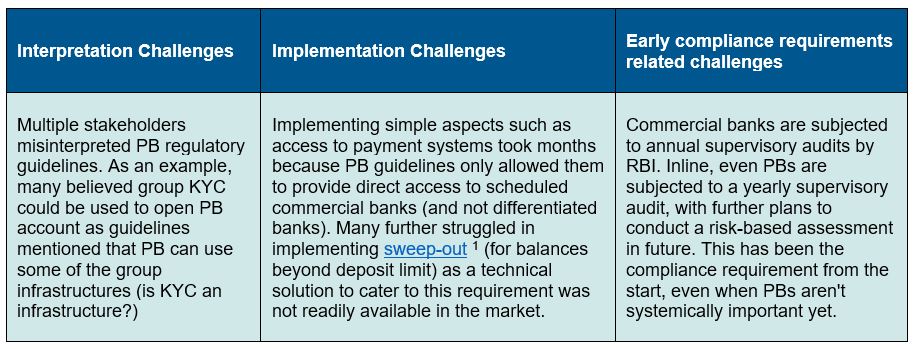

While the requirements mentioned above were laid out from the very start, providers decided to apply for the PB license knowing full-well the potential business implications of these requirements. The applicants looked at the innovative model with optimism (leading to 41 applicants) and tried to build a sustainable PB business with glass half full mindset. Some of the early learnings came in the form of various challenges and opportunities. PBs saw huge potential to serve the 190 million unbanked adults, as envisioned by the RBI. However, initial enthusiasm soon gave way to interpretation, implementation and early compliance-related challenges.

A few interesting macro-policy developments that further stressed the otherwise constrained environment in which PBs operate:

- In 2018, the Supreme Court of India barred private entities from using Aadhaar card for electronic Know Your Customer (eKYC) authentication purposes. This decision adversely impacted PBs with many of them unable to open new accounts because of the lack of process and regulatory clarity. While this changed later and currently PBs are opening accounts using Aadhaar based eKYC, the regulatory void resulted in many months of no new account opening for all PBs.

- In December 2017, the Indian government started a scheme to reimburse Merchant Discount Rates (MDR) on transactions up to INR 2,000 (USD 28) to promote digital payments. This scheme was applicable for two years from January 1, 2018, on all transaction made through debit cards, BHIM UPI or Aadhaar Enabled Payments Systems (AEPS). The Indian central government has further made the MDR on UPI and Rupay debit card transactions zero effective January 1, 2020. MDR being a vital payment flow to banks and other payment service providers, zero MDR leaves them with limited incentive to remain invested and continue upgrading. This will adversely impact the payment providers business.

- Our stakeholder interactions indicate that a later regulatory development clarified that NBFCs could not use PB rails to extend credit or other advances to borrowers with PB accounts. Given the slim margins that PBs operate with, allowing them to lend on behalf of banks and NBFC might provide them with the necessary volumes needed.

However, active PBs are still upbeat about the opportunities ahead. Interactions with active PBs showcased their optimism about the business as they work towards harnessing multiple opportunities in future. Some of the opportunities highlighted during our interactions were:

- Cater to the new to credit customers – The potential to tap into the under-banked and un-banked credit market, by referring customers for credit after PBs have established a healthy payment relationship with these customers.

- Offer insurance and other allied services for bank and other partners as their rails to reach a wider audience.

- Cater to digital-only players to service offline customers – with the rise of e-commerce in the urban markets; many expect e-commerce giants to look at remote/rural markets with PBs as field partners and agents.

- Agent or merchant to act as an ATM for the banking system – India has one ATM for every 5555 citizens, far behind most developed countries. PBs believe that their agent points will be able to act as ATMs (provide cash-in and cash-out services) in markets where customer demand is currently unmet. Some PBs already witness CICO as a healthy use case in some urban and rural pockets

We believe that the factors cited above contributed towards curtailing PBs from realising their true potential of catering to the unbanked in India. PBs seem to have been at a receiving end of a regulatory arbitrage where their offering is no different from a payments aggregator (or the fintechs providing payment solutions) but with comparatively stringent regulatory and compliance requirements. While the current PBs seem upbeat and hopeful about the future sustainability of the model, RBI has also taken some progressive steps such as allowing PBs to apply for Small Finance Bank on-tap licenses to enable them to offer credit.

India’s PB experiment has lots of policy learnings and lessons that regulators globally should consider while planning steps to tackle financial inclusion in their own countries. PBs India story is a live learning ground for regulators and mobile money providers globally who are contemplating aligned narrow banking models in their markets. We will continue monitoring the payments banks landscape in India to effectively support the market and drive meaningful regulatory lessons for our global audience.

Footnotes

[1] PBs are permitted to make arrangements with a scheduled commercial bank / small finance bank (SFB), for amounts in excess of the prescribed limits (INR 100,000), to be swept into an account opened for the customer at that bank.

[2] MDR is the cost that a merchant pays to a bank to accept payment from their customers via digital means. The merchant discount rate is expressed in percentage of the transaction amount.

[3] An ‘on-tap’ facility would mean the RBI will accept applications and grant license for banks throughout the year.

Receive the latest insights on mobile money straight to your inbox by subscribing below.