The mobile industry is forecast to contribute $185 billion to GDP in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2023, and through mobile, nearly 250 million more people are expected to access the internet by 2025 (according to the GSMA’s Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa Report). Countries across Africa can sense the opportunities of this digital transformation for economic growth and societal change, lifting people out of poverty, securing better health and education outcomes, banking the unbanked and providing access to information for all. But to realise these opportunities, individuals need to be able to trust and have confidence not only in the new technology but also in the emerging business models. Data privacy laws are a vital part of this trust-building exercise and it is imperative to get them right at a time when countries across the region are adopting data privacy laws for the first time.

“If we don’t want the Fourth Industrial Revolution to pass us by, data protection in Africa is a pre-requisite,” said Hon. Vincent Sowah Odotei, the Deputy Minister of Communications in Ghana, wrapping up the pioneering Africa-wide data privacy conference that took place in Accra recently. “We don’t have a choice in this matter.”

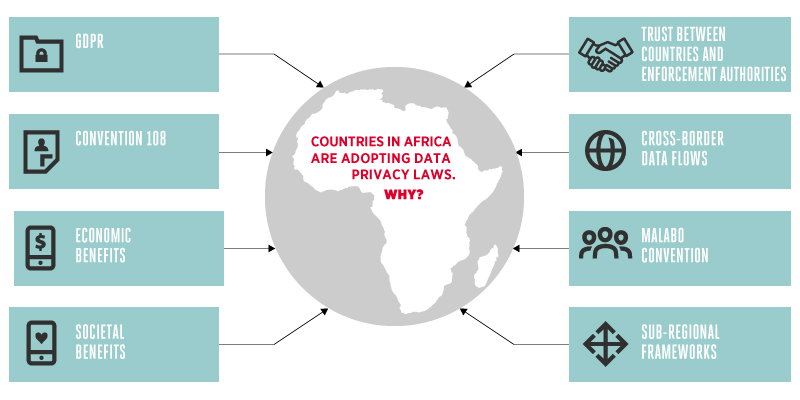

On top of that, countries in Africa face a barrage of external inputs urging them to adopt similar data privacy laws as other countries or regions. GDPR has resonated around the world, but other privacy frameworks have had an influence too. The Council of Europe’s Convention 108 is gaining traction in Africa, the African Union is urging countries to implement its 2014 Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (i.e. the Malabo Convention) and sub-regional initiatives like the ECOWAS Supplementary Act or the SADC Model Law also seek alignment between member states. Although these frameworks head in the same direction, they are inconsistent. For example, in contrast to the SADC Model Law, the Malabo Convention leaves a lot more discretion to signatories to diverge, ignores the concept of accountability altogether and makes only a passing reference to cross-border data flows.

Having laws that align around a common high standard of data protection allows countries to trust each other and enforcement bodies to cooperate. In turn, this can boost the economy by allowing data to flow within the region and it is more attractive for external investors who prefer not to be confined to keeping data in one place.

This is not just relevant in Africa. Regions and economic blocs around the world are doing the same thing. From ASEAN to APEC, from ECLAC to the Ibero-American States, regions are driving an agenda of gradual alignment so that trust and innovation can flourish across their territory.

However, implementing such a law is not easy. There are almost always too many frameworks and examples to draw from and, if drafted poorly, a data privacy law can become over-bearing and prescriptive in a way that stifles innovation and hinders the economy. For example, the use of data from IoT sensors combined with big data analytics and AI capabilities could improve people’s lives around the world. If companies are required to obtain specific consent in each case, such advances become unfeasible, if not impossible. Conversely, the law can enable innovative developments if it provides flexible grounds for processing personal data while insisting on transparency and responsible data governance practices such as privacy impact assessments and privacy-by-design. In such ways, if the law is smart, it can achieve both trust and innovation.

To address this key challenge, the GSMA has published a paper, Smart Data Privacy Laws: Achieving the right outcomes for the digital age, distilling what has been learned from data privacy law implementation to date into guiding principles to consider when passing or implementing a new data privacy law. Essentially, to be smart, a data privacy law must provide effective protection for individuals while also providing organisations with the freedom to operate, innovate and comply in a way that makes sense for their businesses and can secure positive outcomes for society such as Mobile Money or leveraging IoT to increase crop yields. The law should incentivise good data governance through the concept of accountability that puts the responsibility on organisations to identify and mitigate risks. Finally, the law should remain flexible, technology and sector neutral, ensuring a consistent level of protection for individuals and allowing data to move across borders easily.

In Ghana, Deputy Minister Odotei concluded in much the same way: “We need to harmonise our [African] laws so we are part of the world, protect our citizens and can be competitive.” If Africa adopts smart privacy laws, it can not only avoid being left behind, it can leapfrog its way to a brighter future.

To read the GSMA’s report, including its 14 guiding principles, visit https://gsma.at/smart-data-privacy-laws