In developing countries, mobile phones are the most popular way to connect to the internet. The number of unique subscribers using mobile internet in developing countries grew from 728 million in 2010 to 1.8 billion in 2014 . However, women continue to lag behind men in accessing mobile phones and mobile internet.

This week, the GSMA’s Connected Women and Digital Inclusion programmes launched their joint report, “Accelerating Digital Literacy: Empowering women to use the mobile internet”. This report aims to analyse the challenges women face when accessing mobile internet with low mobile literacy and digital skills, understand how women learn these skills, and identify the barriers women run up against in various learning channels. Our findings are based on detailed research conducted through focus group discussions and individual user tests with women in three countries: Kenya, India, and Indonesia.

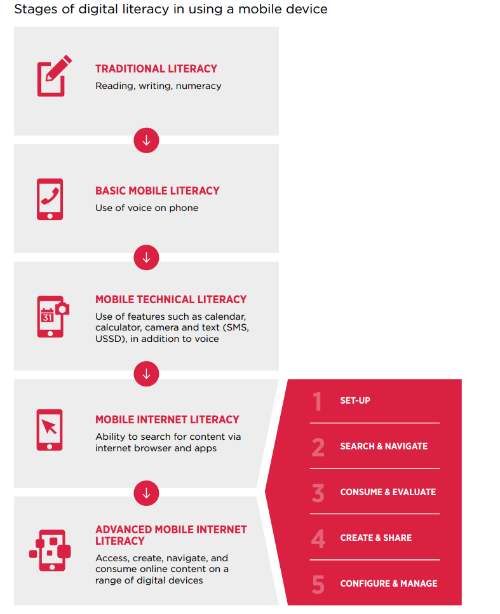

In order to understand mobile literacy and digital skills barriers in the context of mobile internet usage, we first had to examine what is meant by mobile literacy and digital skills. We defined a set of five functional skills to assess participants overall ability to use mobile internet: set-up, search and navigate, consume and evaluate, create and share, and configure and manage. We also evaluated how these five skills relate to the five stages of broader digital literacy for mobile phone usage, as defined in GSMA’s 2014 Digital Inclusion Report (see figure below).

In each country, we tested participants across all five functional skills:

Set Up: Majority of users struggled with setting up internet on their phone and signing up for internet services. Although most users used data plans, they found it difficult to understand traditional volume-based pricing.

Search and navigate: Most of the mobile internet users were able to initiate queries and navigate within the specific applications or services they were familiar with. However, users often struggled to apply these skills to unfamiliar applications, finding themselves stuck on “application islands”.

Consume and evaluate: Most users were able to selectively consume relevant content within familiar applications and services. However, users struggled with finding and evaluating new and relevant content independently.

Create and share: Most users were able to create and share content on popular social media and messaging applications. However, none of the users in the sample understood the concept of creating content for a broader audience beyond their social network.

Configure and manage: Users in all three countries had limited knowledge about managing privacy and content concerns.

Our findings showed that most mobile-only users, as well as the non-users we spoke with, had a limited ‘mental model’ of the internet, lacking an understanding of the depth and breadth of online content – and instead, viewed the internet through the lens of one or two familiar applications or services. It’s important that efforts to promote mobile internet literacy acknowledge these usage differences.

In some countries specific barriers were also identified, such as in Kenya where one smartphone user did not recognise the search icon (magnifying glass) in the Google Play Store, even though she knew how to search for friends on Facebook. Not being able to understand and apply common navigational tools appeared to be more common among users who had only used one or two mobile internet applications or services.

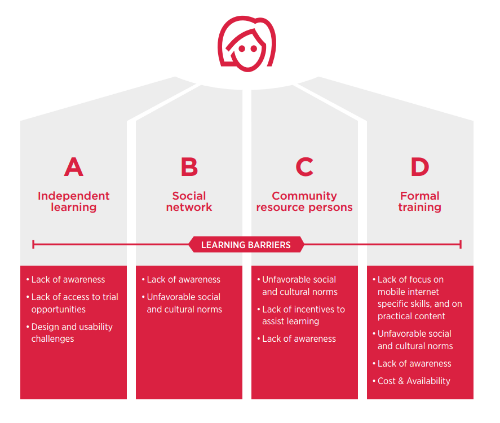

Through the research, we observed four channels or pathways through which women acquired mobile literacy and digital skills: independent learning; their social circle; community resource people, and formal training and education channels. Across all three countries, the women we interviewed appeared to rely heavily on their social circles, especially for set-up, troubleshooting and discovering new applications and services. Women frequently use a combination of the channels, perhaps learning initially from their social circle and then learning other skills on their own. Each of these learning channels can be blocked by a number of barriers, as mapped in the figure below.

We concluded the report with a set of practical recommendations for stakeholders, including mobile network operators, NGOs, governments, handset manufacturers and others, to address these barriers to women’s learning. These recommendations include:

- supporting women to learn skills on their own,

- leveraging women’s social circles as a learning channel,

- expanding learning through community resource people,

- emphasising mobile internet in school curriculum and ICT training,

- improving design and usability in women’s mobile internet experience,

- addressing learning incentives, and

- deepening understanding of women’s mobile internet learning experiences.

The report also includes case studies of organisations which have made headway in improving the mobile literacy and/or digital skills of women in developing countries, including Google; Telecentre Foundation and ITU; the SEWA RUDI Sandesha Vyavhar (RSV); Intel; and the Grameen Foundation, Cashpor and Eko. For example, Google’s Helping Women Get Online programme, which recognises the internet’s role in empowering women in India, has directly trained over 1.5 million women on the basics of the internet since the initiative launched in 2013.