This blog post is the second of a five-part blog series unpacking the findings from our latest report, ‘The digital lives of refugees: How displaced populations use mobile phones and what gets in the way.’

Mobile money is available in 90 countries across the globe, including three-quarters of low- and lower-middle-income countries, making it the leading payment platform for a digital economy in emerging markets. For refugees, the vast majority of whom reside in the developing world (84 per cent), mobile money offers a lifeline to better financial management. This is particularly true in harder to reach locations, where the prevalence of other financial services is often lower.

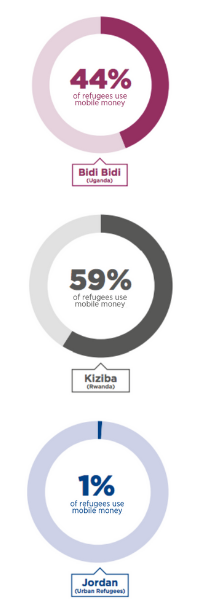

The full report digs deeper into findings and recommendations across five thematic areas – one of which is mobile financial services – in three contexts: urban settings in Jordan, Kiziba camp in Rwanda and Bidi Bidi settlement in Uganda. Due to the low use of mobile money in Jordan – only one per cent of refugees surveyed reported using mobile money – this portion of our research therefore focuses primarily on Kiziba camp and Bidi Bidi settlement.

Mobile money use is high among refugees in Bidi Bidi and Kiziba, offering a secure way to manage finances

Our findings highlight how refugees are using mobile money in their daily lives and what stands in the way of them taking full advantage of the services on offer. Mobile money has the potential to offer refugees a secure way of managing their finances. For instance, Samuel, a refugee in Bidi Bidi, not only earns his living as a mobile money agent and stores his profit from work in his mobile money account, he also serves refugee customers in his area, who no longer have to travel long distances to carry out crucial transactions.

Mobile money use in Bidi Bidi and Kiziba is relatively high and indeed higher among the refugee population in Kiziba than in the host community. Mobile money is also helping refugees improve management of their finances.

“I use mobile money after doing my jobs. I can get some and save it in my mobile money. If you have it in your pocket you may misuse it. And it is more secure.” (Male, Refugee, Rwanda)

Person-to-person (P2P) and airtime top-ups are the most commonly used mobile money services in Bidi Bidi and Kiziba. In Bidi Bidi, where many of the refugees interviewed have family residing in South Sudan, 50% of refugees use international remittance services via their mobile money accounts – a large proportion given remittances makes up a relatively small fraction of total transactions globally.

The use of mobile money is not equal across different segments and a number of barriers exist

Women and refugees with disabilities are significantly less likely to use mobile money in both contexts. Additionally, in Bidi Bidi, older people (over 51) use mobile money significantly less than younger people (aged 18-25) and middle-aged people (aged 26 to 50).

As is the case for forcibly displaced people across the globe and as highlighted in the joint UNHCR and GSMA research ‘Displaced & Disconnected’, the lack of legally recognised identity documentation needed to open a mobile money account is the most significant barrier to using mobile money in Kiziba. In Bidi Bidi, several barriers emerged, including government imposed mobile money taxes (now only applied to cash-outs) and a lack of trust.

“Sometimes, maybe once a week, I don’t have enough float to make transactions for customers. Customers get angry. It happens when I have a lot of customers.” (Male, Refugee, Uganda)

The usual challenges of poor network coverage and liquidity emerged in both contexts, but were more pronounced in Bidi Bidi. Samuel cites these challenges within his work as well. His ability to serve his customers is limited by these frustrations. Additionally, the ambiguity on how taxes are applied to mobile money transactions in Uganda has pushed his customers to think twice about whether to use mobile money in certain situations.

Bolstering the evidence base to support refugee livelihoods through mobile money

In spite of the challenges highlighted, our findings provide an opportunity for mobile network operators and humanitarian organisations to build on this research to increase understanding of how refugees are using mobile money in their daily lives and barriers hampering their ability to take full advantage of services on offer. This research aims to help shape MNOs and humanitarians’ strategies that improve beneficiary experiences with mobile money and unlock even greater potential for mobile money as a tool for improved financial management.