Kenya’s agriculture sector is crucial to the country’s economy and its people’s livelihoods. Agriculture accounts for 31.5 per cent of GDP and employs 38 per cent of the population. Over the last few years, the country has seen the emergence of digital tools that aim to deliver efficiencies for agricultural stakeholders, such as smallholder farmers, crop buyers and agribusinesses.

Most of these digital solutions exploit the widespread use of mobile phones and availability of mobile money in Kenya to formalise agricultural value chains and enable financial inclusion by digitising payments to farmers. In a new GSMA AgriTech report, we look at some of these digital agriculture tools, specifically to understand how they might be able to enable financial inclusion for smallholder farmers. We look at three specific use cases:

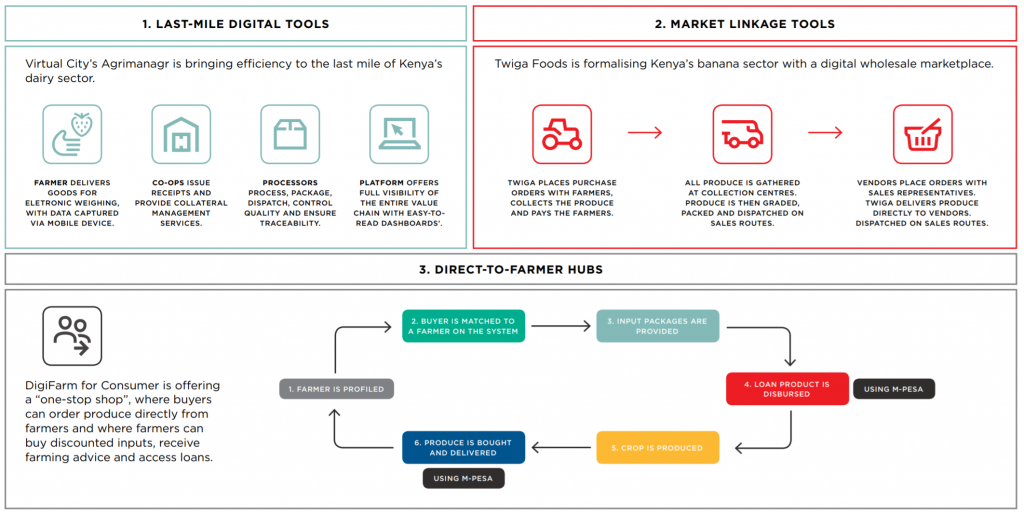

- Last-mile digital tools that replace manual processes with mobile-based solutions that digitise transactions (i.e. procurement payments, digital receipts etc.) and streamline communication between smallholder farmers and agribusinesses. Examples include Virtual City and DigiFarm for Enterprise.

- Market linkage tools that formalise agricultural value chains by allowing crop producers and buyers to connect through a mobile-based online platform. Examples include Twiga and Tulaa.

- Direct-to-farmer hubs as “one-stop shops” through which third-party agricultural service providers offer their services directly to farmers registered on the hub, while farmers can take orders directly from buyers. The most prominent example of this kind of solution is DigiFarm for Consumer.

By addressing pain points for their users (farmers, agribusinesses, crop aggregators and crop buyers), these tools generate a large volume of farm and farmer data that can be used to create economic identities and improve financial inclusion for farmers. The first step towards generating an economic identity involves the registration of farmers and the creation of digital profiles on the system including personal data and data on their farming activities.

Next, transactional histories are established through the use of mobile money, initially when farmers receive payments from agricultural buyers for produce sold. Over time, as mobile money adoption takes up, transactional histories are generated through further mobile money usage for utility payments or input loan repayments. Eventually, sharing farm and farmer data with financial institutions opens to the opportunity to perform credit risk assessment for farmers and enable loan disbursements, which are especially required for long-term asset financing.

In Kenya, despite the volume of farm and farmer data generated by digital agriculture tools, data sharing for farmer financial inclusion generally remains fragmented and limited. During our field research, agribusinesses controlling data cited concerns over entrusting data to third parties, while the lack of a best practice on how to share, such as a centralised data exchange hub, has restricted data exchange to bilateral agreements. For instance, e-commerce platforms such as Twiga Foods and Tulaa, share their data to offer loans and credit inputs respectively. Twiga Foods has collaborated with a loan provider, while Tulaa has collaborated with an input supplier, with both solutions offering tailored additional services to their vendors and farmers respectively. These examples show that agribusinesses are likely to have the strongest incentive to share data in order to provide their farmers with additional services, such as financing for inputs. This enables farmers to improve the quality of their crops and increase their yields, and establish a formal value chain with agribusinesses.

All of the solutions we surveyed were keen to share their data with third parties that can provide additional services to farmers and recognised the importance of obtaining consent from farmers to share their data. However, educating and informing farmers on how their information may be used remains a challenge. Some solutions employ field agents to discuss data sharing consent with farmers, while others provide information via SMS or USSD. Despite these efforts, farmers’ understanding of how their data is used remains uncertain. Our study also yielded contrasting claims to data ownership amongst solution providers. Most solutions we spoke to claimed ownership of the farm and farmer data they collected – with the exception of Tulaa. Tulaa only claimed ownership of any data that they had analysed, with raw data belonging to their farmers.

Further detailed analysis on how to improve smallholder financial inclusion by creating economic identities through digital financial data can be found in our recently published report.

We welcome your feedback and comments on this report.