The ubiquity, affordability and capability of mobile technology can make it a powerful tool in delivering life-changing products and services in many contexts, including during humanitarian crises. GSMA research demonstrates the degree to which people affected by crises are using mobile technology and highlights how it is being leveraged to deliver services as diverse as energy, education and agriculture. However, it is important to acknowledge the inequities that can exist in regards to access to mobile, particularly for vulnerable groups. If actors do not ensure that technology is readily available and usable by all groups then they run the risk of entrenching disenfranchisement when services are digitised.

This case study explores the degree to which mobile technology is available and used by refugees with disabilities in three unique contexts (Bidi Bidi Settlement (Uganda), Kiziba Camp (Rwanda) and amongst refugees in urban settings in Jordan). It highlights the challenges they can face in accessing mobile and the self-perceived benefits it can bring. We believe that if products and services are designed in a way which is inclusive to those with specific needs they will more equitably serve the entire customer base.

Until now the size of the “mobile disability gap”, or how much less likely a person with disabilities is to own or access a mobile phone than a person without, has not been quantified in refugee contexts. The gap is important; persons with disabilities are often disproportionately affected by crises and can “fall through the cracks” in terms of accessing products and services. This can mean this group may be excluded from aid or services to which they are entitled.

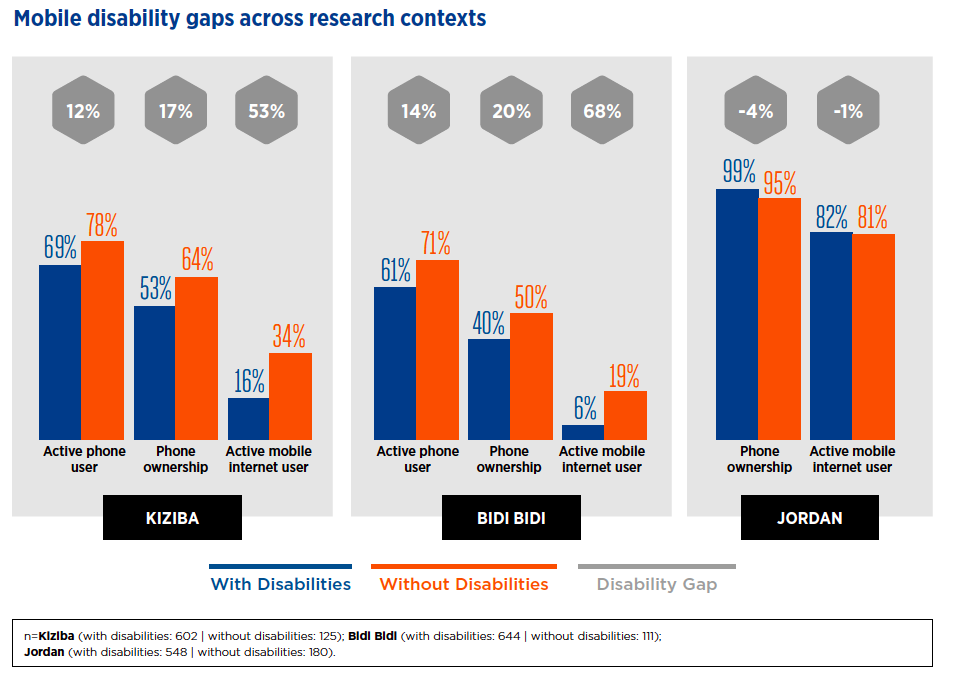

In two of the three contexts, there was a notable mobile disability gap

The GSMA survey found that refugees with disabilities were 17% less likely than those without to own a mobile phone in Kiziba and 20% less likely in Bidi Bidi. The gaps increased to 43% and 68% respectively when looking at the proportion of each group reporting being an active user of mobile internet. This was not the case in Jordan, where regardless of disability status, almost all research participants reported owning a phone and roughly eight in ten were using mobile internet.

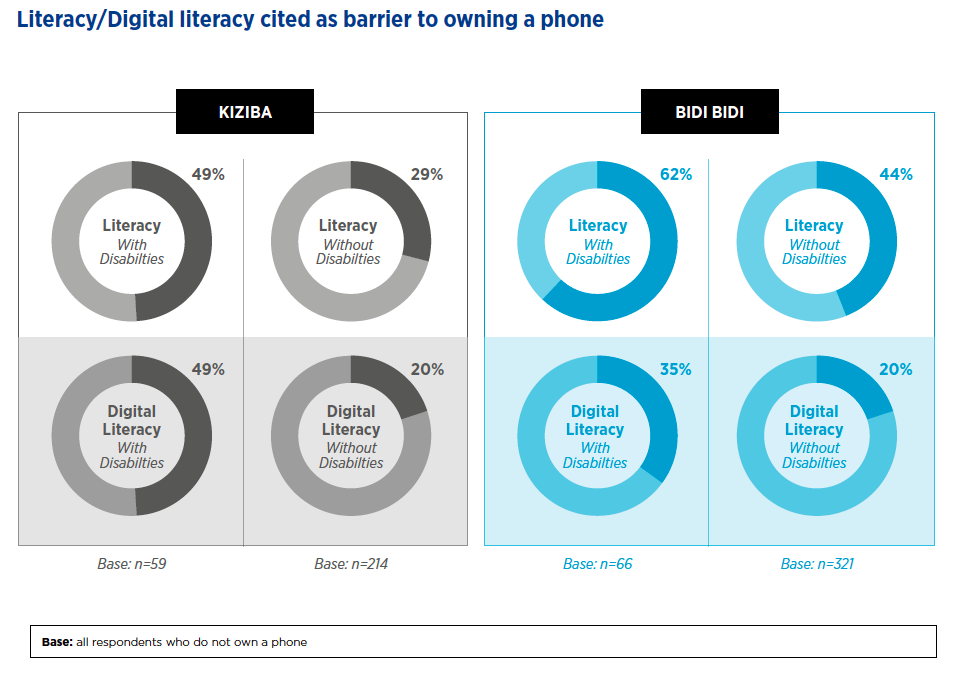

Many people with disabilities reported not having the prerequisite skills to make use of mobile requiring support to develop them

Amongst refugees with disabilities in Kiziba who did not own a phone, 49% reported that a contributing factor was that they had difficulty reading or writing and 49% also said they did not have the skills to use a phone (digital literacy). This was notably higher than those refugees without disabilities. A similar trend was evident in Bidi Bidi. It may be that humanitarians and technology providers need to support these users in upskilling, either formally through trainings, or through other informal means.

Refugees with disabilities report numerous perceived benefits attached to their use of mobile

In focus groups with persons with disabilities, participants mentioned a number of ways in which mobile technology was improving their lives. Examples ranged from gaining immediate access to information and support to providing entertainment. Through these first-hand accounts it is clear that mobile can be used as an effective channel to deliver value-added products and services in humanitarian contexts.

“It makes me forget my problems, when I start thinking of what is happening at home I listen to music [on my mobile phone] to help me forget.”

– Refugee with disabilities, Bidi Bidi settlement

More needs to be done

It is essential that all partners in the ecosystem understand any inequity in the penetration of digital in the contexts that they work. Beyond this, actors should work together to address this inequity and ensure they design services in a way which is inclusive of all their users, taking into account any specific access requirements.