There are two choices for mid-band mobile. Here are the sums.

Pressure on mid-band spectrum is increasing and governments are looking for answers as to how to satisfy demand for 5G. International agreements on mid-band spectrum have long-since been outstripped by national decisions in 5G markets while demand is growing fast. Excessive assignments to unlicensed technologies or vertical carve outs all put pressure on 5G spectrum, lowering 5G speeds and raising prices. The solutions are still there to deliver the promise of 5G, but governments need to ensure that maths adds up.

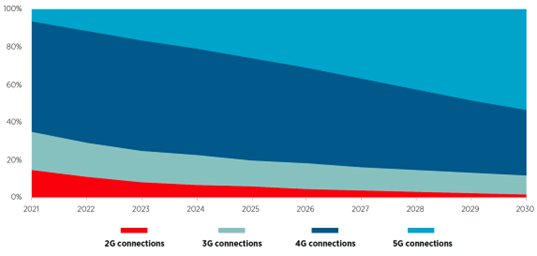

Assignment of mid-band spectrum was the starting point for 5G, in most cases using the 3.5 GHz launch range. About 11% of the world’s mobile connections are already on 5G today, and as networks mature that figure will reach over 50% by 2030. At that point 5G will be at the height of its impact on our businesses, economies and lives. Consequently, the greatest demand will be placed on mid-band spectrum. The mobile industry is as agnostic as possible about how that mid-band demand can be met. In reality, countries are addressing this in only two ways:

- By maxing out the 3.5 GHz range (3.3-4.2 GHz) up to 4.2 GHz and even considering below 3.3 GHz

- By relying on adding more spectrum using 6 GHz

Global Technology Curve – % Mobile Connections 2021-2030

GSMA Intelligence

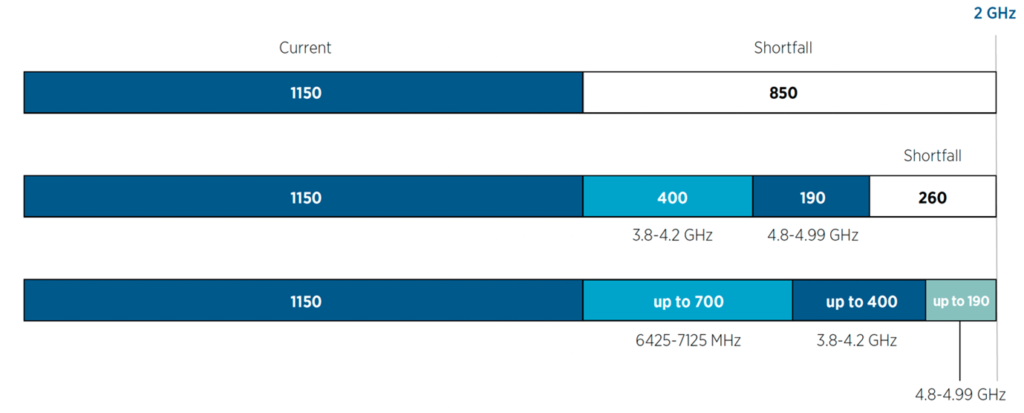

Mid-band will deliver the most economic value of the three spectrum ranges – low, mid- and high bands – that are required for 5G. If mid-bands are constrained to today’s levels, the economic value of 5G – the number of people using it and the productivity enhancement that its quality allows – will reduce by 40%. To flourish, mobile requires 2 GHz of mid-band spectrum to meet demand by 2030. This is a challenging goal to achieve in all countries, but the earliest adopters are starting to move closer through assignments and in their spectrum roadmaps. Importantly, mid-band activity at WRC-23 can help achieve that figure in reality.

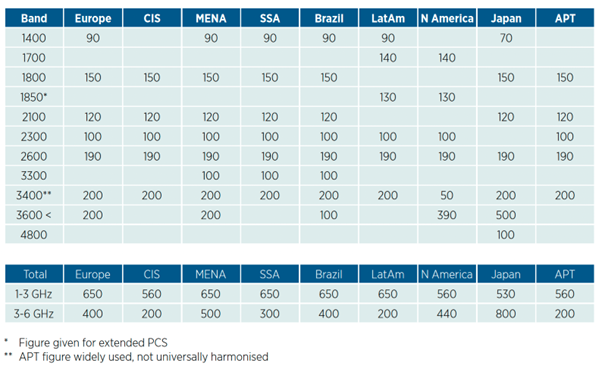

Today, around 650-750 MHz of mobile spectrum is typically available between 1-3 GHz. In the more mature 5G markets 4-500 MHz of 3.5 GHz spectrum usually supports city-wide 5G, meaning a total of around 1150 MHz is typically available to day. While the size of the remaining shortfall varies, there is work to by all governments and regulators to meet long-term demand.

Operator investment in every new frequency layer is vast – both in the acquisition of spectrum and subsequent network upgrades – and finding the right spectrum assets is important. Channel size is paramount and, with the possibility of new mid-band assets delivered in the late 2020s being considered for 6G in some markets, will become even more so in the future. Harmonisation is also vital and increasingly there are two clear harmonised options to look at with their own ecosystems and solutions that will provide the bulk of capacity.

Mid-Band Maths – Solutions Point to 6 GHz

The upper 3.5 GHz range is being developed in some countries. The same is also true for spectrum immediately below 3.3 GHz and in the 4.8-4.99 GHz range. Licensin g this capacity for mobile is an important step. However, do the mid-band maths and you will see that, the 190 MHz of 4.8 GHz spectrum and up to 400 MHz of 3.5 GHz simply will not meet the shortfall.

Despite that, countries which are not looking elsewhere – including Saudi Arabia and the US – have shown leadership in looking at every conceivable MHz both in and near to the 3.3-4.2 GHz range. This will not be an option for everyone.

3GPP Band 104 (6425-7125 MHz) is variously knowns as U6 GHz or the upper 6 GHz band. U6 GHz has 700 MHz of spectrum which is barely used for one of its allocations (fixed satellite) and more heavily used for mobile fixed links. An internal change of use within the mobile industry (from backhaul to access) would not come without cost, but it can be managed. U6GHz gives you a tailored solution for solving the mid-band equation. Read more about the band here.

The mid-band maths are fairly simple: mobile needs an average of 2 GHz by 2030. The balance will be decided in every market and the numbers are that if you take out 6 GHz, you need to max-out 3.5 GHz and then look elsewhere as well.

What form that ‘elsewhere’ may take is not too clear for the mobile industry. So, for countries that want to invest in the future of mobile, deployment of the upper 6 GHz and identification at WRC-23, is the only way to get the sums to add up. Learn more about else is at stake at WRC-23 here.

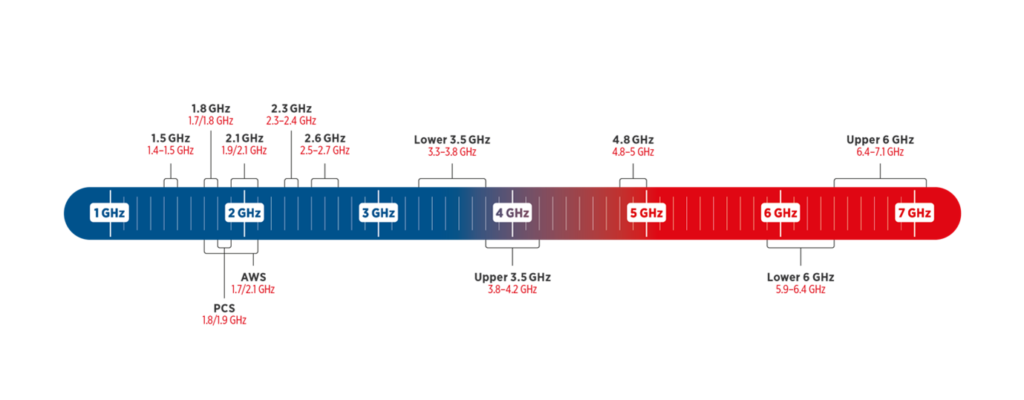

Typical Mid-Band Mobile Spectrum