This blog has been co-authored by Dario Giuliani (Founder of Briter Bridges) and Sam Ajadi (Senior Insights Manager, Ecosystem Accelerator team).

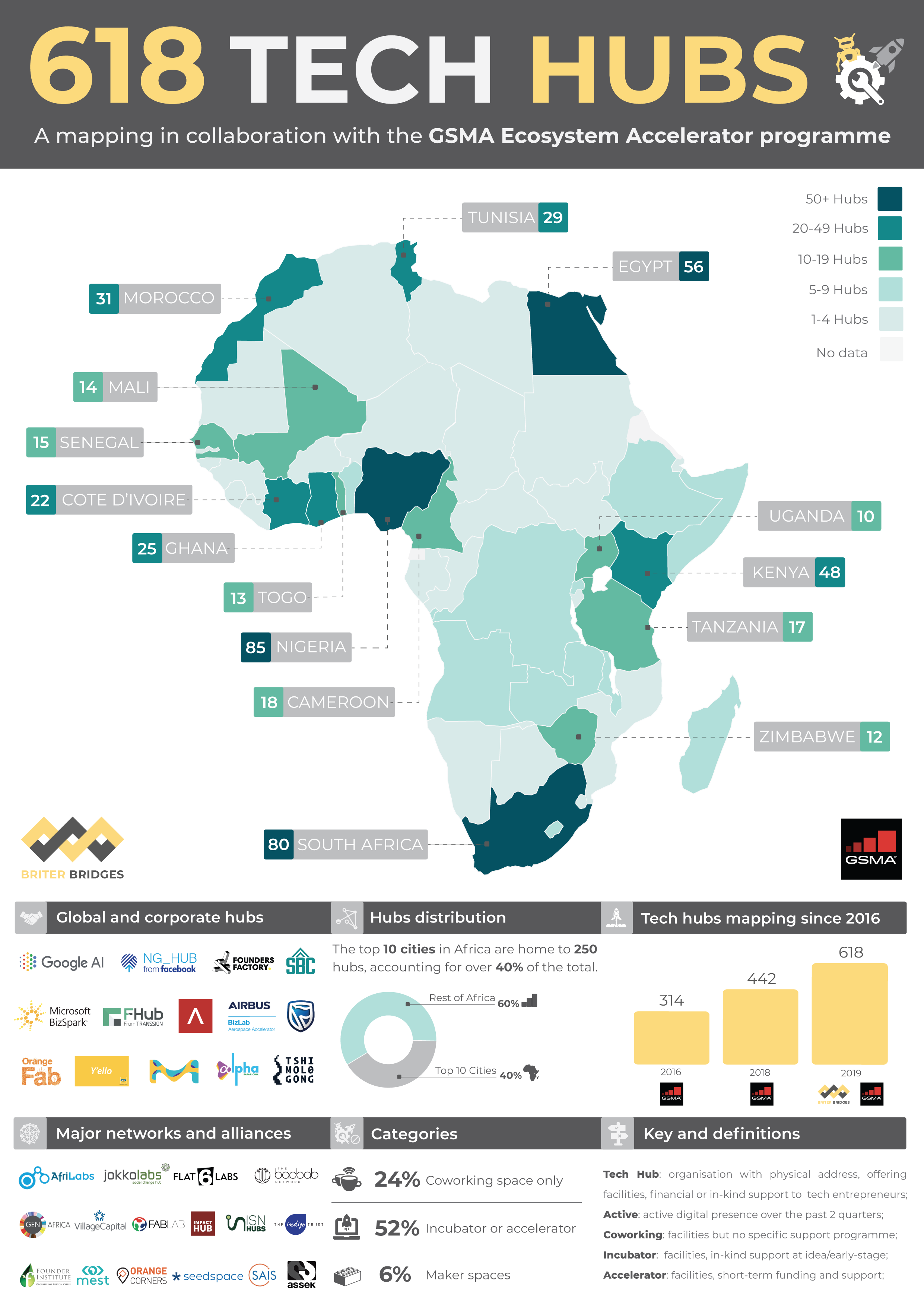

Technology ecosystems across Africa have witnessed incredible growth over the past few years, mainly boosted by a torrent of venture funds, development finance, corporate involvement, as well as ever-growing, innovative communities. The latest collaborative effort by Briter Bridges and the GSMA Ecosystem Accelerator programme, identifies 618 active tech hubs. This figure is based on the GSMA’s 2016 – 2018’s definition – an active tech hub being an organisation currently active with a physical local address, offering facilities and support for tech and digital entrepreneurs. The 2019 figure represents a 40 per cent leap since last year’s study, which counted 442.

The hubs categories have been predominantly based on the type of support or facility offered to entrepreneurs, and include incubators, accelerators, university-based innovation hubs, maker spaces, technology parks, and co-working spaces. It is, however, worth noting that 25 per cent of the active total hubs only offer co-working facilities instead of specifically tech-focused support programmes or funding. However, we considered it appropriate to include such organisations in light of the broader social role they play in the tech community, as safe spaces for the youth and catalysts of digital professionals.

Key findings from the 2019 mapping

The innovation quadrangle: Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt and Kenya

Nigeria and South Africa remain the most advanced ecosystems, boasting 85 and 80 active tech hubs respectively, offering well-established collaborations and investment networks. Lagos is now the top innovative city by number of hubs (40+), while Western Cape, Gauteng and, increasingly, Durban, are the core of South Africa’s tech hubs scene.

Kenya, already established as the heart of East Africa’s technology ecosystem, with almost 50 tech hubs, represents the Eastern point of this innovation quadrangle, and new investors and corporates are flocking to Nairobi every week, looking to seize the fast-growing pool of tech talents in the country.

Egypt, with 56 active hubs, is positioned as the de facto node between the African and Middle Eastern ecosystems. Cairo, among the top urbanising cities globally, has now grown to become one of the top three cities by number of hubs across the continent, competing only with Lagos and Cape Town. In addition, Cairo is home to one of the largest pools of leading venture funds, including Algebra Ventures, A15, and Sawari Ventures and several large start-ups that have recently shaken the headlines, such as Swvl, due to their massive funding rounds.

From Cairo to Casablanca: The rise of North Africa’s tech scene

Besides Egypt, Morocco (31) and Tunisia (29) have been fuelling the rise of North Africa’s entrepreneurship, with Casablanca and Tunis boasting circa 20 hubs each and gradually positioning themselves as fertile ground for start-ups – especially after the 2018 ‘Startup Act’ was put forward by the Tunisian government to encourage start-up creation and growth in the country. Tunisia, which in 2016 was called out as MENA’s next start-up hub, has benefitted from a vibrant ecosystem and the work of organisations such as Entrepreneurs of Tunisia, who contributed to building mapping tools of the country’s ecosystem.

Francophone West Africa’s promise starts becoming reality

The GSMA Ecosystem Accelerator team, Gregory Omondi and Maxime Bayen at Jokkolabs Dakar

Francophone West African countries have recently been put under the spotlight, recognised as some of the fastest-growing ecosystems on the continent. The governments of France and Senegal in particular, as well as international institutions such as the African Development Bank, have committed large sums of money to boost SMEs and the digital ecosystem in the region. Additionally, some of the major venture funds now active in Africa have set up offices in Dakar, such as Orange Digital Ventures and Partech Partners. Our research shows that Côte d’Ivoire continues its race to becoming Francophone West Africa’s leading innovative ecosystem, with over 20 hubs, Seedspace and four different Jokkolabs locations, followed by Senegal (15), home to major VCs in the region and to the newly founded Dakar Network Angels. The mapping also reveals that, besides Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, Mali (14) and Togo (13) have shown rapid signs of awakening in the region, while elements of nascent and growing ecosystems are present in Benin and Burkina Faso.

The rise of new tech cities: Established and emerging players in perspective

Though the top 10 cities account for more than 40 per cent of total active hubs, with 250 organisations, this mapping highlights that several non-capital cities are emerging as new, sophisticated cradles of innovation.

This study categorised different tiers of cities according to the number of active start-ups headquartered there and their location. Following this methodology, each country is likely to have one ‘main’ city where the tech ecosystem has developed and ‘secondary’, fast-growing satellite ones.

Here is a break-down of the 15 main tech cities:

- Lagos, Cairo, Cape Town, Nairobi, and Johannesburg belong to Tier 1, with 20 to 40 hubs each;

- Casablanca, Accra, Abidjan, Tunis, and Abuja follow suit as Tier 2 cities, with 15+ hubs each; and

- Dakar, Bamako, Kampala, Dar Es Salaam, and Lomé with 10+ hubs are the latest emerging cities.

It is worth noting that many of the above-mentioned emerging cities have recently launched angel networks and have joined regional or international tech alliances.

Yet as previously mentioned, nascent technology scenes are being registered beyond the core cities and sprouts of ecosystems are now taking shape in places such as Kumasi (Ghana), Bulawayo (Zimbabwe), Lubumbashi (DRC), and Mombasa (Kenya), where rapid urbanisation and improving education systems are creating the fabric needed to support the growth of technology ecosystems. Some of the notable hubs in these cities include Kumasi Hive and Hapaspace, the Centre for Innovation of Lubumbashi, and Bulawayo’s Tech Village.

Liquid Telecom partners with several hubs across Africa. The image shows The Innovation Village in Kampala.

Innovation flourishing in unstable contexts

A large part of this study is the product of months of conversations with local players from Dakar to Maputo. This has allowed us to broaden the research beyond the usual few countries who champion innovation on the continent and to investigate the work being done by ecosystem players in geographies. These include Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique – which are rarely under the spotlight for tech innovation due to their exposure to civil unrest, environmental disasters, or biohazards. However, these countries are now home to several hubs scattered across their territory and have witnessed the rise of tech initiatives such as the Mogadishu Tech Summit in Somalia and Kinshasa Digital Week in DRC. Although sporadic programmes and hubs also launched in South Sudan and Central African Republic, a few such as Centrafrique Tech Hub in Bangui and, with the upcoming involvement of the UNDP through its Accelerator Labs, minor ecosystems are likely to see increased coverage in the future.

Corporate partners and venture capital

A large number of hubs across the continent have been supported by mobile operators and internet providers, due to their close involvement in the digital space. Orange has been setting up Orange Fab labs across Francophone Africa, while MTN and ICT infrastructure providers such as Liquid Telecom have also launched in-house tech hubs initiatives (like MTN Y’ello Startup in Abidjan) in several markets on the continent. While mobile operators have been among the frontrunners in corporate partnerships, not only playing a role in enabling the ICT infrastructure upon which digital services have been implemented, but also investing in tailored programmes over the last couple of years, large tech companies are also supporting the ecosystem by establishing a physical presence. Among these are the Google Launchpad Accelerator, Facebook NG_Hub in Lagos, the Microsoft Development Centres in Nairobi and Lagos, and IBM and WITS’ Tshimologong District in South Africa. Notably, more traditional corporations such as Standard Bank have entered the game by setting up incubators across several geographies, including lusophone countries such as Mozambique and Angola. Similarly, Standard Chartered Bank recently set up eXellerator in Nairobi.

In 2019, Bizlab by Airbus launched an aerospace accelerator in Africa through the #Africa4Future initiative, in partnership with GIZ Make-IT in Africa, MEST and Innocircle. Last May, Nestle, in partnership with Kinaya Ventures, announced the launch of their R&D Innovation Challenge to identify and scale novel ideas (tech and non-tech) related to sustainable food packaging, distribution, and nutrition. Large pharmaceuticals such as Merck and Sanofi have been running entrepreneurial contests for years in Accra and across the continent. Recently, Shenzhen’s handset giant, Transsion, has also made its first move into Africa’s tech scene by setting up its own Future Hubs in Lagos and Nairobi.

As African start-ups are becoming increasingly appealing to an international audience, several global brands such as Y Combinator, Startup Bootcamp, and Founders Factory have established a greater presence on the continent.

Although this study specifically decided to exclude them from the count, training programmes and bootcamps are increasingly becoming part of the tech scene all across the continent. Google Developer GroupsFacebook Developer Circles, Forloop Africa, and Andela Learning Community are but a few of the dozens of techie communities across the continent. Several hubs are also providing targeted, internal mentoring programs to students and women and, finally, startups themselves are launching intrapreneurial labs such as Africa’s Talking, who is setting up its own labs to train local developers and founders. Finally, among the actors playing a cohesive role, there is enterprise builder Village Capital, who, in August 2018, was supported by DFID to launch its Communities programme, aimed at strengthening 15 hubs across the continent.

Joining forces: Increasing efforts to build alliances and networks

Although most of the major trends encountered in the 2018’s study continue along the same trajectory this year, ecosystem actors across several countries seem to agree on the need for more consolidation and collaboration. This is reflected in the increased number of hub alliances, shared programmes, and deeper conversations among stakeholders from all across the continent.

Not all that glitters is gold- this study reiterates a high churn rate as over 150 hubs seem to have shut down operations since 2016. This denotes the lack of maturity and diversity of certain business models adopted across the continent – a volatility which lies at the foundation of a growing debate around the sustainability of such hubs and their actual role in the tech ecosystem. This, and the need to create a collaborative agenda built on common interests, have been the key rationales behind the major efforts towards hub consolidation across the continent, with ecosystem builders from Cape Town to Nairobi calling for better cooperation and dialogue within and across countries.

This increased commitment to coordinate efforts across ecosystems has led to the establishment of several local and international networks of hubs. While Afrilabs, with over 150 members across more than 45 countries, remains the single largest network, several local alliances have emerged in the past year, such as Nigeria’s Innovation Support Network, which gathers 75 members, and Kenya’s ASSEK with over a dozen members and currently onboarding more. Other more established networks are the Southern Africa Innovation Support organisation, which is headquartered in Windhoek, or Flat6Labs, the largest network of technology hubs in the MENA region and spanning from Tunis to Lebanon.

In practice, fragmentation means that each of the 54 African countries face their own regulatory hurdles when it comes to doing business, and tech hubs and their stakeholders have played a cohesive role in facilitating engagement and a productive discourse between the public and private sectors.

Bottom-up policy-related initiatives are also becoming prevalent as they contribute to improving the regulatory framework around small enterprises and innovation. Perhaps the most notable is i4Policy from 2018, which has consisted of a collaborative effort involving over 100 hub managers and aimed at putting forward protocols enabling better business climates. These, and similar ‘Startup Acts’ have now been carried out in Tunisia, Senegal, and Mali.

Moving forward

A major step forward will be likely to derive from the progressive alignment of interests and agendas of the different stakeholders but this requires further understanding of each organisation’s role within the ecosystem. To begin with, there is a need to build a more accurate and comprehensive taxonomy of the various players, starting from hubs. Then, investors and donors will be likely to create more impact by intensifying the dialogue with existing players instead of investing in re-creating the wheel.

Overall, what this research has observed is the growth of many ecosystems across the continent to a degree of maturity which is translating into a better coordination between entrepreneurs, hubs, angel networks and the donor space. Additionally, corporate ventures and donors from UK Department for International Development (DFID) to the AfDB are now increasingly looking at startups and innovative SMEs as targets for funding and support, and we are witnessing several tech giants establishing a physical presence on the continent. All indicators, from venture capital funding to the number of tech hubs and growth rates across tech ecosystems all across the continent, are showing no signs of slowing down as more players enter the race and funding is made available. This study aims to contribute to creating a more transparent body of information and indicate the key actors working to drive the ecosystem forward.

Briter Bridges collects, analyses and visualises data on technology ecosystems across emerging markets. To learn more about Briter’s mapping work please visit briterbridges.com

The Ecosystem Accelerator programme is supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Australian Government, the GSMA and its members.