In 2019, the GSMA Mobile for Humanitarian Innovation (M4H) team worked with Ground Truth Solutions in Burundi to understand users’ experience of receiving cash assistance through mobile money. The work used human-centred design (HCD) methodologies to empathise with users and better understand, from their perspective, how programming could be improved.

To provide more information about how this work was conducted and some of the outcomes, I spoke with Max Seilern from Ground Truth Solutions.

Zoe: Thanks for joining me Max. I wanted to start the conversation by saying first how excited we were to do this piece with you. Ground Truth Solutions has a track record of producing these user journeys around cash assistance in a number of contexts. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about your past work?

Max: Thanks for having me! Our fascination with user journeys began back in 2017. At the time, the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) put out a call for applications to explore the experience of the “whole” of cash and voucher assistance (CVA). FCDO recognised that payment systems used in CVA were often built to serve the needs of agencies rather than their users and wanted us to look into the expectations, needs, and overall experience of CVA recipients. So, we partnered with Ledia Andrawes from Sonder Design and with the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and set off to Iraq and Kenya to improve the user experiences of different payment systems.

Since then, we’ve adapted our user journey approach to understanding experiences of CVA and have made it a key component of our Cash Barometer initiative, funded by the German Federal Foreign Office, in the Central African Republic, Nigeria, and Somalia. We also used a similar approach to look into how to mitigate risks to CVA recipients in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and are now finalising user journeys of Syrian refugees receiving cash assistance from WFP in Lebanon.

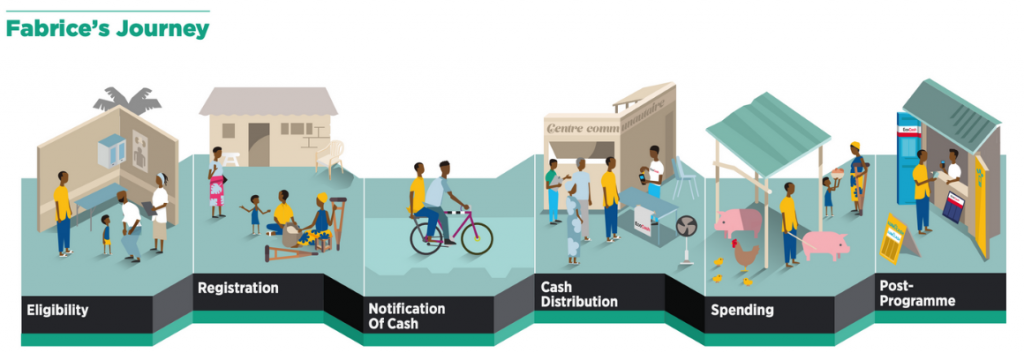

I think this approach resonates with CVA providers because it speaks to individuals’ entire experience of the assistance they receive. It allows us to understand their actions, feelings, perspectives, and frame-of-mind across different stages of receiving CVA, so that they can be individually evaluated. By building a shared understanding of these experiences, we bring together different actors involved along users’ journeys to explore how their experiences can be improved upon.

We also know that GSMA M4H has been using human-centred design beyond this project. What was unique about this piece of work for you?

Zoe: Yeah it’s interesting, we also have done some work recently using human-centred design methodologies in Kenya. Unlike this project, we worked with Butterfly Works to use the participative HCD tools with end users themselves. So, while in this work we used semi-structured interviews and a variety of visual tools to understand users’ experiences, which we later visualised in the user journeys, in the Kenya research we had users themselves, for example, visualise their journeys as we, the facilitators asked probing questions. Traditionally, this methodology has been used in product and service design, but we found it really useful to understand user experiences and needs from a research and insights perspective. We think the broader sector could benefit from this methodology as well, starting with understanding users’ perspectives can help to ensure that programmes are designed effectively, with various user needs taken into account, but even on a more basic level it can help us understand what users prioritise and what challenges they’re facing.

Max: Absolutely. The analytical power of this methodology lies in its ability to shift our understanding of programmes from an operational or system-centred view to one that is sensitive to the complex and very unique pathways recipients take through programmes. It allows us to document their first-hand accounts, to understand what enhances or frustrates them, and to develop recommendations.

Ideally, this isn’t just a one-off exercise but something that is integrated into on-going monitoring efforts. User journeys are a great way to explore some of the “why” questions you might be left with after collecting and analysing survey data. They work well when trying to understand the experiences of certain types of recipients that may not be well understood.

Zoe: Agreed! So let’s talk a little bit about the work specifically that we did together in Burundi. I don’t know if you agree, but this was one of the lowest digital literacy settings our team had ever worked in, which presented some challenges. What did you think?

Max: What struck me in Burundi was that recipients’ experiences and the resulting user journeys were fairly similar. As a result, it was difficult to pin down demographic or situational characteristics that resulted in more or less positive experiences. I think much of that was due to the specific targeting approach of Concern’s mobile money programme coupled with low digital literacy.

The programme provides mobile money to households with acutely malnourished children to ease the stress of the lean season in Kirundo province. As such, targeted recipients were in the same area, affected by the same lean season and all cared for acutely malnourished children. In addition, most had little to no experience using mobile phones and mobile money. Given these similarities across recipients, the first-person accounts provided by our 18 interviewees ended up being quite similar, despite having been purposively sampled to explore different experiences. Ultimately, their experiences were all frustrated by their lack of familiarity with mobile money and by not having access to mobile phones, making it difficult to pick up on other frustrating and enhancing aspects of their experiences.

Zoe: Yes and I think that highlighted a key recommendation for us. This goes back to your comment on shifting from an operational standpoint to one that’s sensitive to recipients’ lived experience of the programme. So often humanitarian organisations use mobile technology because it improves efficiency and makes life easier for them, which is great. But there are so many benefits that end users could also reap through digital programming if they had access to mobile devices and were trained in how to use them. If that’s baked into programming, which it is in some of Concern’s other programming, then users can use those phones beyond the direct programme — taking full advantage of the social and economic benefits that can come with owning and using a mobile phone, ensuring people receive more than just the value of cash they receive.

Max: Fabrice’s user journey really speaks to that potential. Like some of the other personas, he has been told not to use the SIM card for anything but receiving and withdrawing mobile money from Concern. Across our quantitative survey we found that 70 percent had never used a mobile phone and only 9 percent reported owning one. In that context and faced with constraints that prevented them from providing mobile phones to recipients, Concern had to prioritise access to transfers over long-term digital inclusion. However, doing so meant missing out on certain knock-on effects that come with receiving a SIM card. As Fabrice tells us:

“I know how to use a phone but I was afraid to use the project SIM because I was afraid of disturbing something. There was someone who was not given money because he changed something on the SIM card. I was afraid to risk losing money for my family. But I plan to use Ecocash if I can and to call friends if it doesn’t damage the SIM card.”

Fabrice

His fear of doing something wrong, of losing out on assistance, prevents some of the positive knock-on effects that he could benefit from.

Zoe: One of the benefits of this type of visualisation is it allows us to see the programming from the users’ perspective to see really clearly what works and doesn’t work for them. It allows us to pick up on these really intuitive ways to improve programming and experiences for the user. We found things like having people they can trust by their side, transparent and accessible assistance, and building in cash to longer-term financial support were all things that improved users’ experiences.

Max: An important step in this process is to have everyone involved in the CVA programme come together to review the user journeys and develop recommendations. Most of the learning usually occurs at this stage – when different actors involved build a shared understanding of recipients’ experiences. In Burundi, our co-creation workshop brought together staff from Concern and Cassava Fintech Burundi, the mobile money provider. Their expertise was vital in making sense of the user journeys and how they could be improved upon going forward. The personas developed as part of this project can also be a useful tool toward that end. They can guide decision-making going forward to ensure that recommendations and programme adaptions made in the future work for different types of recipients.

Zoe: Another thing I know we’ve spoken about in the past is how we both hope others will use this type of methodology as well. Whether working as a researcher or creating programming to serve marginalised populations, working from a user perspective can help to gather insights that can improve the experiences for all user types. By including marginalised communities and understanding their perspectives, we can make programming that works for them.