According to the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, an estimated 10.6 million persons with disabilities are forcibly displaced globally. These populations are at greater risk of violence, stigma and exclusion. Mobile technology and the digitisation of services can bring wide-ranging benefits to people with disabilities, but can also present barriers if not designed appropriately. As digital solutions become more central to life in general and the humanitarian sector, it is more important than ever to take these populations into account when considering the role of mobile technology.

To better understand the lived experiences of these populations, the GSMA Mobile for Humanitarian Innovation (M4H) team initiated a research project with UNHCR and Safaricom along with the GSMA Assistive Tech team. M4H wanted to work with Kenyans and refugees with hearing and visual impairments in Nairobi, to better understand the opportunities mobile-enabled solutions could provide.

The digital lives of refugees and Kenyans with disabilities in Nairobi is a new publication that sheds light on the mobile-enabled opportunities for displaced peoples with disabilities in Nairobi. By exploring both the ways these populations are currently using mobile technology and the opportunities for mobile technology to ease access to services – the report makes recommendations for both humanitarians and mobile network operators (MNOs) to create inclusive services around several themes.

Human-Centred Design methodologies

An accompanying report Human-Centred Design in humanitarian settings: Methodologies for inclusivity shares the methodology used in this research so evidence gaps around the lived experiences, barriers and mobile-technology based opportunities can be filled in other settings.

Figure 1: A group of hearing impaired research participants engage in an activity.

We used human-centred design methodologies as they are particularly suited to work with marginalised communities helping researchers better understand the user’s perspective. These populations tend to have fewer opportunities to voice their experiences and influence decision-making processes. At the same time, they face complex systemic challenges. To shape solutions that will effectively address these challenges, their perspective is absolutely critical. Human-centred design research methodologies are well suited to the challenge because they bring the perspective of this end user to the forefront.

The report includes research tools that can be used in other contexts, as well as the adaptations that were made to research tools to ensure they were inclusive. A forthcoming blog will delve deeper into these tools.

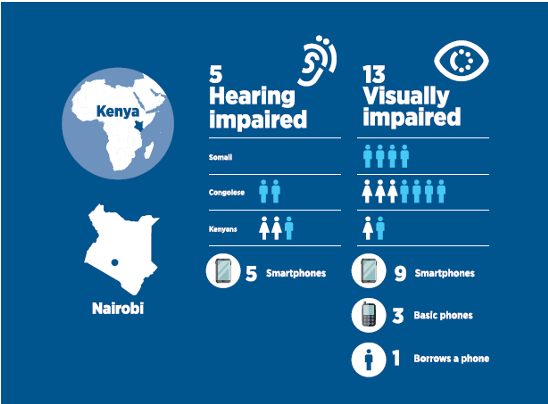

Figure 2: our research participants.

Five key insights

The research started with several open ended questions that allowed participants to shape the direction of the research. Four service areas were identified as both being relevant to research participants and having opportunities for mobile-based interventions. These areas were: (1) mobile phones and mobile services (2) health (3) financial and (4) refugee or disability support services.

The report includes insights and opportunities related to each theme – first as it related to participants with hearing impairments and then to participants with visual impairments.

Across these service areas, five key considerations for creating mobile-enabled opportunities emerged:

1. The importance of community

When working with marginalised communities, including both people with disabilities and refugees, it is imperative to reinforce existing ties and create additional ties to the wider community. Participants said that they often felt isolated but cited religious communities as key sources of support. Digital interventions should be integrated into these on-the-ground communities in order to ensure support is available at multiple levels.

2. Increased livelihood and entrepreneurship opportunities

Generally, these groups expressed feelings of dependence and a desire for greater autonomy. This included a desire for financial independence, especially through entrepreneurship, increased financial literacy and opportunities to give back to their communities. Increased trainings and opportunities for these groups, for example through Village Savings and Loans groups, would be welcomed.

3. Digital skills are key

Mobile technology can play a transformative role for people with disabilities. It can help people to be more independent, to feel safer and to access services with more ease. However, many research participants had low digital literacy skills and were unaware of assistive technology tools, like screen readers. Greater training and support could help people with disabilities access the full range of benefits digital inclusion can bring.

4. Access to consistent information and appropriate services

Users reported that they didn’t have a clear understanding of what support services were available to them. This included support as a refugee or asylum seeker, as a resident of Kenya in terms of access to mobile and health services or employment, or as a disabled person. Information and services should be clearly signposted and efforts should be made to ensure that services are fully accessible to prevent people from falling through the cracks in accessing services. Mobile technology can fill this gap by providing both clear information on services, follow up mechanisms and communication assistance. For example, applications for information and follow ups, along with sign language translation services could be immensely useful.

5. Communication challenges

Research participants, especially the hearing impaired, faced challenges in communicating, especially with service providers like health professionals or mobile money agents. As not everyone can use sign language and many services are voice-based, like call centres or hotlines, participants sometimes felt marginalised. Creating accessible alternatives and welcoming environments, including both non-voice based services and trainings on the needs of people with disabilities, can help people to access the information and services they need.

How to take this forward?

While the findings of this research are contextualised to the experiences of refugees and Kenyans with hearing and seeing impairments in Nairobi, these overarching insights may be relevant to other contexts. Organisations working in humanitarian response, can take these considerations into account when considering how to ensure people with disabilities are included in digital services. UNHCR, for example, has launched a call for proposals for their country offices who want to develop solutions related to the barriers identified in this research.

More detailed information on these findings can be found in the Digital lives of refugees and Kenyans with disabilities report.