Mobile phones and harassment of women

The first of a featured series, this opening post attempts to provide an overview of how mobile and the wider telecommunications industry can be leveraged, not only to tackle mobile-based harassment, but also more broadly gender-based discrimination in emerging markets today.

For women, mobile access is the key to an informational space previously dominated by men. Sadly though, women continue to face security and harassment issues, the topic of a recent Connected Women blog, giving perpetrators yet another platform for discrimination and intimidation. Harassment via mobiles, along with security concerns around carrying mobiles, were listed as two of the biggest barriers to female ownership and usage (3rd largest), after handset/ credit cost and network quality and coverage, in Connected Women’s 2015 report on “Bridging the Gender Gap: Mobile access and usage in low and middle-income countries”. The latest post on the topic, “Kenya and the Rise of the Call-blocking App”, discusses the recent surge in mobile apps designed to reclaim a secure and private space for female Mobile for Development (M4D) users. Apps highlighted include Trucaller, a programme that reveals the identity and location of unknown callers, returning a measure of control to women on the receiving end of mobile-based harassment in the form of anonymous phone calls.

Products and services targeting gender-based violence and harassment

But why stop at mobile-based anti-harassment tools, when technology is so often most creatively implemented through a marriage of the digital and the actual? It’s worth highlighting that the success of M4D tools does largely hinge upon public awareness and willingness of the given community to tackle the issue at hand. A lack of successfully scaled mobile campaigns in this field suggest that in the absence of public action, mobile tech becomes ineffective and actually risks causing more damage than good. To clarify, if there is no one at the other end of the line to take the problem seriously, then why bother reporting it at all? Expecting too much from tech in this way can be harmful to those already vulnerable to these crimes, creating a façade of progress when behind the smoke and mirrors, the structural problems still remain. However, when local demands, digital skills, and support services are considered, and the many clusters of the mobile industry come together to support this innovation, M4D services demonstrate capacity to bridge the real-world/digital world divide for social good.

My overall impression gleaned from research and interviews leads me to believe that the current range of products and services (mobile & non-mobile) targeting gender- based violence (GBV) and harassment can be delineated into 3 overarching camps: preventative, emergency response, and reporting and evidence building. However very few have so far managed to successfully integrate all 3 areas into 1 programme. These can be represented via a cyclical format, as some facets no doubt feed into other impact areas, i.e. prevention through advocacy created by evidence building, or harassment reports filed as a result of police alerts via emergency response features.

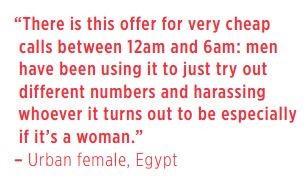

Via a diverse digital toolkit, M4D could equip social sector actors with all manner of applications and services that would extend the overall reach of their projects. One such facet of Egyptian NGO, Harassmap’s campaign is an SMS-to-web reporting platform, encouraging users to flag up incidences of sexual harassment against women on the streets. Users text in reports of harassment that they have witnessed or experienced to a shortcode SMS number, following which the report is stored in an online database and illustrated via a Ushahidi platform in the form of a hotspot map. This data then forms the basis for diverse community outreach campaigns targeting harassment hotspots (a model that’s been replicated in a smattering of other emerging markets such as Yemen, Bangladesh, Palestine, and India). In combination with these tech-centric efforts, they try to tackle mobile-based harassment with a nation-wide media campaign highlighting the reality that this, too, constitutes a form of crime under the newly established anti-sexual harassment law. In a country where both men and women reported practice of men randomly dialling numbers in hope of reaching women, such initiatives are key in providing a safe space within which female users can operate, whilst confronting the root source of the discrimination itself: a perfect example of how mobile can be harnessed for social impact.

Via a diverse digital toolkit, M4D could equip social sector actors with all manner of applications and services that would extend the overall reach of their projects. One such facet of Egyptian NGO, Harassmap’s campaign is an SMS-to-web reporting platform, encouraging users to flag up incidences of sexual harassment against women on the streets. Users text in reports of harassment that they have witnessed or experienced to a shortcode SMS number, following which the report is stored in an online database and illustrated via a Ushahidi platform in the form of a hotspot map. This data then forms the basis for diverse community outreach campaigns targeting harassment hotspots (a model that’s been replicated in a smattering of other emerging markets such as Yemen, Bangladesh, Palestine, and India). In combination with these tech-centric efforts, they try to tackle mobile-based harassment with a nation-wide media campaign highlighting the reality that this, too, constitutes a form of crime under the newly established anti-sexual harassment law. In a country where both men and women reported practice of men randomly dialling numbers in hope of reaching women, such initiatives are key in providing a safe space within which female users can operate, whilst confronting the root source of the discrimination itself: a perfect example of how mobile can be harnessed for social impact.

India and Nepal-based Safecity is another example of a sexual harassment reporting platform that makes use of mobile tools. This particular NGO has adopted a more preventative stance towards Violence Against Women (VAW) through mobile by advertising apps that map out security threat hotspots and women-only taxi pick-ups. Their Missed Dial facility also provides a free call-back service for females with no access to internet to file a harassment report (contributing more to a body of evidence than providing security at the time of the incident).

Supplementing this, the world’s first “Domestic Violence Hackathon” took place in Washington DC last year, organised in the name of designing services for both basic and smartphones to tackle GBV in Central America. Winning entries included an SMS service to alert friends and family to attempts to traffic girls abroad for arranged marriage, and SMS domestic violence information and job finding services (http://buff.ly/1O8xIL7). This flurry of innovative activity highlights efforts to increase inclusivity of M4D services, extending these necessary tools to the less digitally equipped communities that arguably lack them the most. Criticism has naturally arisen around lack of intuitive design for women in high-pressure or violent situations. Ronda Zelezny-Green (GSMA Connected Living), for one, has highlighted the need for simplicity and stripped back features in this instance. She shows how a feature as simple as allowing victims to record soundbites of the crimes can have a powerful impact on the prosecution outcome at a later date. It just goes to show: innovative doesn’t have to be overly intricate; sometimes basic is best!

Smartphones= not always so smart?

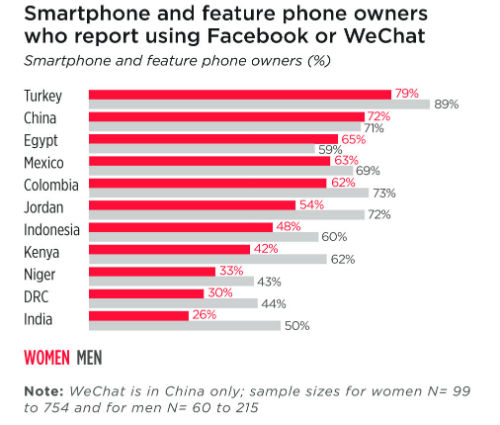

Another sizeable chunk of the Women and Mobile portfolio is made up by emergency response services, i.e. the SOS alert smartphone app. This vein of services typically provides quick access to pre-programmed contact numbers in case of an emergency, allowing users to report incidents of harassment and receive speedier assistance. Applications can be pre-configured to dial or text personal contacts or in some cases, police and medical services. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent they will succeed in protecting female users in underserved mobile markets. Take Egypt, for instance: high rates (pp. 30) of feature phone social media use indicate the existence of a mobile ecosystem conducive to app uptake, when conversely, female users in India typically have access to more basic models, rendering them less digitally literate and therefore less likely to benefit from high-brow smartphone services. Can we speculate then, that Delhi Police’s emergency response safety app for Android, Himmat, actually segregates security, favouring the more affluent segments of user communities? Or simply just falls short in terms of user needs and intuitive design? All in all, and albeit perhaps an obvious point, we need to look into the unique user environment of each country before designing these tools, to ensure they’re even needed and what’s more, inclusive. In the same vein then, local content creation deserves a nod to here, highlighted by the Local world — content for the next wave of growth report. This is a key point to ensure the inclusion of the next billion mobile internet users, of which a growing number are women.

Data for justice

In addition to mobile reporting frameworks, it appears that more targeted data collection tools are quickly becoming front-runners in the wider scheme of GBV prevention/prosecution services. One such example is an application brandished in the battle to track down and prosecute perpetrators of rape in the Democratic Republic of Congo, namely the Physicians for Human Rights’ (PHR) MediCapt programme. This smartphone-enabled service aims to provide a digital solution to collating and documenting medical evidence of sexual violence in conflict zones, complete with forensic photographic capabilities. After receiving the USAID Humanity United Tech Challenge award for Atrocity Prevention in 2013, it’s set for release in the coming year, and aims to provide a secure, encrypted framework through cloud data storage and “tamper-proof metadata”, in addition to functionality in low-connectivity areas and a variety of user languages.

In the same category of justice-driven data collection, reports have surfaced about the pilot testing of an M4D programme being used to track anti-witchcraft violence in Papua New Guinea. Research conducted by the Australian National University indicates that accusations of sorcery often occur in the emotional aftermath of funerals, and typically fall upon female shoulders. This initiative seeks to stockpile evidence in the hope of spurring forth a wave of public action condemning the femicides. Volunteers use coded SMS messages to document & monitor deaths and any cases of ensuing violence: a key exercise in collating a body of evidence for future reconciliatory efforts.

Yet despite the need for empirical evidence, the risk here is that endless one-dimensional platforms are constructed, filling countless digital filing cabinets with data that serves no other purpose than to illustrate the prevalence of an issue. What’s more, by giving voice to victims of gender-based crime through mobile, an expectation is often created (and not unreasonably so) that organisations are able to provide solutions in return. Yet, in many cases, rudimentary harassment reporting platforms via mobile unknowingly provide false hope, with no support network in place to cope with the mounting calls and texts for help. The next obvious step then appears to be the creation of a mobile response mechanism that could convert M4D tools from data storage units to platforms of exchange. Khaled Hijab of Jordan-based Tech Tribes initiative, 7arkashat, told of his frustration in the challenge of constructing the next supportive phase of their anti-harassment project: “By asking people to report, you are instilling hope that you are able to provide a solution”.

However, actually creating an effective and transparent support network via mobile is not always a walk in the park (This topic will be explored in more depth in the following post of this Security and Harassment blog series).

We stand witness to an exciting moment for women and mobile, with services catering to all number of female security demands. Yet, while it is tempting to pat ourselves on the back, it’s crucial to avoid treating technology in absolutist terms, and necessary to use a critical eye. Ultimately, the tools are only as ready as the environment in which they are deployed. Meaning,

1) M4D services for harassment and VAW prevention and support must be tailored to the demands and the capabilities of the users they’re designed for (male/female, digitally literate/ illiterate, cost appropriate), and

2) Albeit with great potential, mobile is an auxiliary tool: anti-harassment M4D programmes will only be effective in an environment where the wheels of change are already in motion.

It’s about time we took a closer, more critical look at the capabilities and shortcomings of mobile services in combatting gender-based harassment and violence through tech. Ultimately, until these divisive aspects of technology are reframed, M4D risks perpetuating and exacerbating gender-based hierarchies instead of serving as a weapon to eliminate them. The more we can incorporate these concepts into M4D design and implementation, the bigger the benefits we will reap, and the faster we will narrow the gap, making sure that mobile is a stepping stone to gender equality, and not a roadblock along the way.