Plastic, the quiet polluter

Last week, over 25,000 representatives from 200 countries arrived in Madrid for the COP25 Climate Change Conference, where they hope to reach agreements on how to fight against the effects of climate change. According to the UN’s Emissions Gap Report, released ahead of the COP25, greenhouse gas emissions surged to a record level in 2018 and the global mean temperature will probably pass the 1.5°C point of no return established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Currently researching plastic challenges and recycling initiatives in developing countries, I came across some disturbing plastic facts and figures. While scientists, NGOs and the civil society urge governments and businesses to cut global emissions by more than 7 per cent every year until 2030 to stay below the 1.5°C threshold – plastic production is growing almost anonymously, as does its carbon footprint.

Currently researching plastic challenges and recycling initiatives in developing countries, I came across some disturbing plastic facts and figures. While scientists, NGOs and the civil society urge governments and businesses to cut global emissions by more than 7 per cent every year until 2030 to stay below the 1.5°C threshold – plastic production is growing almost anonymously, as does its carbon footprint.

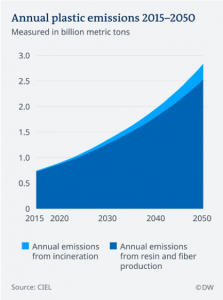

According to the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), the 2019 production and incineration of plastic will have produced more than 8.5 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases. The plastic production also consumes about 4 per cent of annual total use of oil and gas worldwide.

It is estimated that 8.3 billion metric tons of plastics have been produced since the malleable and light material made its appearance in our everyday lives several decades ago. Half of the plastic we produce is for single-use items. We enjoy it for less than one hour but it remains on the planet for several hundred years. Around 12 per cent of all plastic waste has been incinerated, releasing in its wake carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. In addition to the accumulation of yesterday and today’s plastic waste, the global plastic production is expected to double over the next 10 to 15 years with growth fastest in countries with a lack of reliable waste-management system.

Whether we like it or not: plastic is here to stay.

The vast majority of plastic waste is discarded – but where does it go? It ends up either in landfills affecting people’s health and livelihoods and the natural environment, including the oceans. Healthy oceans play a vital role in the climate system, they generate oxygen and act as a sponge for carbon dioxide, absorbing it from the atmosphere. Plastic litter that kills marine species and micro plastics that contaminate the food chain reduce the oceans’ ability to act as efficient carbon sinks.

In the GSMA’s CleanTech Programme, we see digital technology as an enabler for developing countries’ transition towards low-carbon, climate-resilient economies. We are currently conducting landscape research on the global plastics challenge, in order to identify and highlight best practices and innovation in plastic waste management, particularly in the countries that are least able to deal with it.

Incentive-based initiatives using smartphone technology to build attractive recycling systems have flourished in many developing countries. If plastic litter harms our planet, plastic waste – smartly collected and recycled – can become highly valuable for the poorest and contribute directly to most of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Plastic in the bank

The Plastic Bank is a “chain of stores for the ultra-poor, where everything in the store is available to be purchased using plastic garbage.” said The Plastic Bank’s founder, David Katz. The blockchain-based app is free to download and offers a way for locals to get paid outside of traditional currency. Beyond food and goods, the stores launched by a Canadian start-up also offer mobile services such as Wi-Fi and solar power phone charging. The plastic waste collected is recycled and sold to global brands for packaging use under the name of Social Plastic – as an ethical alternative to virgin plastics. The Plastic Bank has stores in the Philippines, Haiti and Indonesia and plans to expand in Ethiopia and India.

The Plastic Bank is a “chain of stores for the ultra-poor, where everything in the store is available to be purchased using plastic garbage.” said The Plastic Bank’s founder, David Katz. The blockchain-based app is free to download and offers a way for locals to get paid outside of traditional currency. Beyond food and goods, the stores launched by a Canadian start-up also offer mobile services such as Wi-Fi and solar power phone charging. The plastic waste collected is recycled and sold to global brands for packaging use under the name of Social Plastic – as an ethical alternative to virgin plastics. The Plastic Bank has stores in the Philippines, Haiti and Indonesia and plans to expand in Ethiopia and India.

From marginalised waste pickers to ethical traders

The strategy of the platform Plastic for Change is similar to fair trade agriculture. It’s designed to provide urban waste workers with access to fair market prices through mobile devices – as well as improved social and environmental standards. It creates transparency and accountability from the base of the supply chain to the manufacturer. Operating in Bangalore and now expanding to coastal communities across south East India to reduce ocean plastic, the platform enables global corporate clients to improve their social and environmental impacts by purchasing ethically sourced recycled plastic. Plastic for Change is the first recycler to be verified by The World Fair Trade Organization.

The strategy of the platform Plastic for Change is similar to fair trade agriculture. It’s designed to provide urban waste workers with access to fair market prices through mobile devices – as well as improved social and environmental standards. It creates transparency and accountability from the base of the supply chain to the manufacturer. Operating in Bangalore and now expanding to coastal communities across south East India to reduce ocean plastic, the platform enables global corporate clients to improve their social and environmental impacts by purchasing ethically sourced recycled plastic. Plastic for Change is the first recycler to be verified by The World Fair Trade Organization.

Turning trash into cash

Packa-Ching are local mobile recycling units travelling across low income communities and schools in South Africa to buy recyclable waste from residents on specific days. The initiative addresses logistical and security-related challenges by taking the recycling facility to the doorstep of remote communities and using a cashless e-wallet payment system that eliminates the risk of dealing with hard cash. Community members bring their bags of recyclable packaging material, including plastic, paper, metal cans and glass, to the truck to be checked, weighed and exchanged for a monetary value. The money earned is paid in real time into a cashless e-wallet payment system called eVoucher.Mobi. The funds are immediately available to spend at participating merchants to purchase airtime or to transfer to anyone in South Africa, all via a mobile phone. There are no transaction or transfer costs, the only fee charged to the user is 20c for dialling the USSD platform.

Packa-Ching are local mobile recycling units travelling across low income communities and schools in South Africa to buy recyclable waste from residents on specific days. The initiative addresses logistical and security-related challenges by taking the recycling facility to the doorstep of remote communities and using a cashless e-wallet payment system that eliminates the risk of dealing with hard cash. Community members bring their bags of recyclable packaging material, including plastic, paper, metal cans and glass, to the truck to be checked, weighed and exchanged for a monetary value. The money earned is paid in real time into a cashless e-wallet payment system called eVoucher.Mobi. The funds are immediately available to spend at participating merchants to purchase airtime or to transfer to anyone in South Africa, all via a mobile phone. There are no transaction or transfer costs, the only fee charged to the user is 20c for dialling the USSD platform.

Over the next few months, the CleanTech programme will continue to deliver research on the global plastics challenge in order to showcase current tech innovations and identify potential research and market engagement opportunities. If you would like to partner with us in this effort, or if you know of innovative plastic waste initiatives between mobile network operators, tech innovators, non-profit organisations and the public sector, please comment below or reach out to me at [email protected].