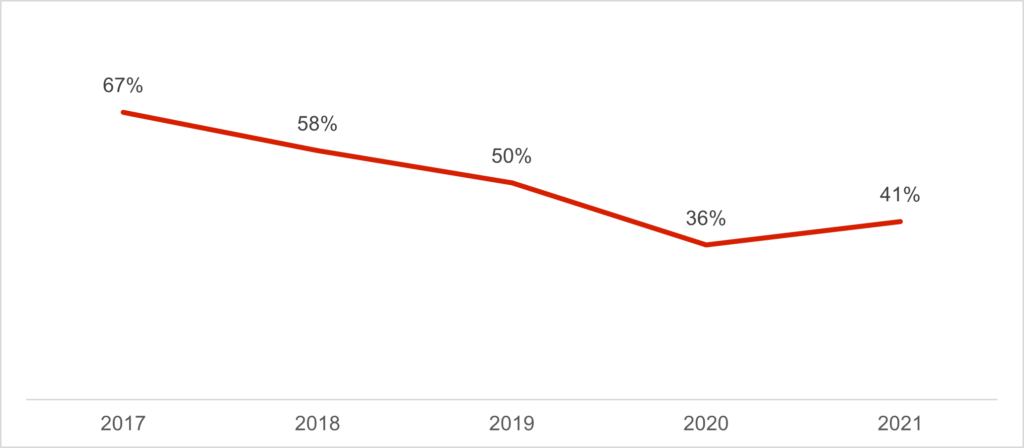

Mobile internet can be a life-enhancing tool that makes people feel more autonomous, safe and connected, especially women. Yet, women in South Asia are substantially less likely than men to access mobile internet. Across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), South Asia has consistently had one of the widest gender gaps in mobile internet since Connected Women began tracking it in 2017. Currently, women in South Asia are 41% less likely than men to use mobile internet, compared with 16% across all LMICs. Having said this, significant progress was being made and the gender gap in South Asia was decisively narrowing, but in 2021 this trend changed. Data from the Mobile Gender Gap Report 2022 showed that, while men continued to adopt mobile internet, there was no notable increase among women. As a result, the gender gap in the region widened to 41% in 2021, reversing the positive progress that had been made between 2017 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Gender gap in mobile internet use across South Asia, 2017-2021

N.B. The gender gap in mobile internet use describes how less likely women are to use mobile internet than men.

It is, of course, important to note that these regional figures for South Asia mask country-level disparities. For example, in Pakistan the gender gap in mobile internet use continued to narrow from 43% in 2020 to 39% in 2021. However, in Bangladesh and India it widened for the first time in 2021 to 48% and 41%, respectively. The overall South Asia gender gap was particularly affected by the change in India where the underlying penetration of mobile internet use among men increased from 45% to 51% while it remained flat for women at 30%.

In 2021, women in India, like most across the world, were disproportionately impacted by the lasting effects of the pandemic and this extended to mobile internet uptake. GSMA qualitative research conducted at the end of 2021 found that these negative effects were felt most by poor and less educated women, and as such further limited their ability to pay for a handset or data. In fact, our quantitative survey data revealed that 14% of female mobile users (compared to 7% of male users) in India who were already aware of mobile internet said that the cost of data was the biggest reason why they did not yet use it – a relatively high percentage for a country that objectively has the some of the most affordable data packages in the world.

On top of the effects of the pandemic, women’s underlying lower levels of employment and the gender pay gap mean that they have always felt the affordability barrier more acutely than men. The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity Report 2022 highlighted that in South Asia, despite entry-level handsets becoming more affordable in 2021 they are still three times less affordable for women compared to men.

Yet, access and use of mobile is inhibited by more than just affordability – a lack of basic literacy, limited digital skills and, safety and security concerns to name a few examples. Women’s mobile use, and particularly that of women in South Asia, is also limited by social norms, including gatekeepers denying access, for instance due to their concerns that women are vulnerable to threats from the negative side of the internet that may bring the family reputation into question.

Our research has revealed that women in Pakistan and Bangladesh reported that family disapproval was one of the top three barriers stopping them from owning a mobile phone. Furthermore, in Pakistan, a woman’s mobile ownership is often preceded by sharing a device and even once she owns one it is still common for her to share her passwords with male gatekeepers so they can maintain access to the handset.

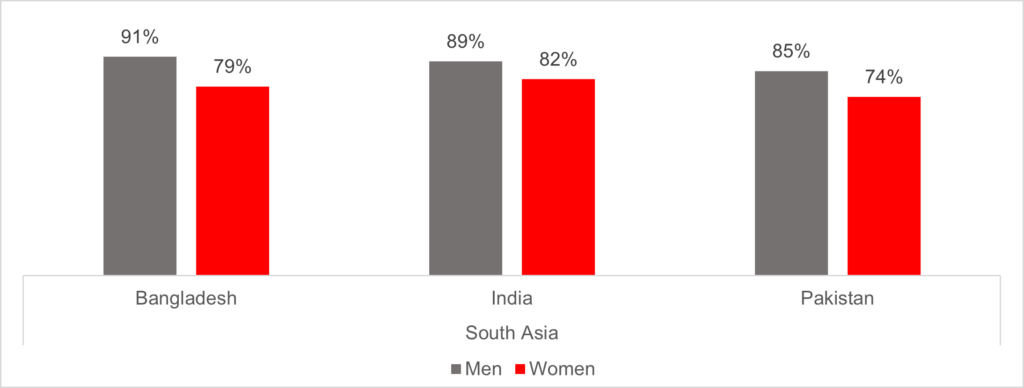

These are just a few examples of how social norms can inhibit women not only from having diverse, regular and safe mobile internet use but even in their ability pay for, choose, or own a mobile phone. Across the survey countries in South Asia, we found that women have less autonomy in paying for and choosing the model of their device. Even when women paid for their handset themselves, they are still less likely than men to select the type of model (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mobile owners who chose the model of their mobile themselves – among those who obtained a new device in the past year and paid for it themselves

A concerted effort is required to ensure the digital inclusion of women in South Asia

Promisingly, much of the progress in digital inclusion that women in South Asia experienced at the start of the pandemic was not lost, but continued efforts are needed to prevent gender gaps from widening further. This will require multi-stakeholder collaborations to comprehensively address the barriers women face, all the while keeping in mind the structural inequalities and social norms that women face in the region. We also need to continue generating quality gender-disaggregated data to inform targeted actions to reach women in South Asia.

Connected Women estimates that closing the gender gap in mobile ownership and use could generate a 14% to 44% increase in revenue for the mobile industry in the South Asian countries surveyed. On top of this commercial opportunity, closing the mobile gender gap will bring considerable social benefits to women in South Asia, their families, communities and beyond.

See more insights from our recent webinar on tackling social norms to reduce the digital gender divide in India in partnership with BBC Media Action.

The Connected Women programme is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), and is supported by the GSMA and its members.