Money is changing form, and how we make payments is also changing. The use of cash is slowly falling in most countries, according to recent research by the IMF. The rapid innovation in the payments space has accelerated the demand for digital money.

Though licensed commercial banks have been issuing digital money, more recently, there has been an influx of private entities authorised by the central banks to issue electronic money (e-money) to e-wallet holders. Mobile money, for instance, which is a regulated e-money offering, has become a global payment mechanism, with 316 operators providing digital financial services to 1.35 billion account holders that transacted over a trillion dollars across 98 countries last year, based on the GSMA’s latest State of the Industry report. Digital money products are becoming more sophisticated to cater to the diverse needs of users.

The interest in digital money has moved beyond private issuers to governments. Many countries are considering issuing a digital form of fiat currency. In fact, some countries have already launched what is being called a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), which is digital money produced and issued by a central bank.

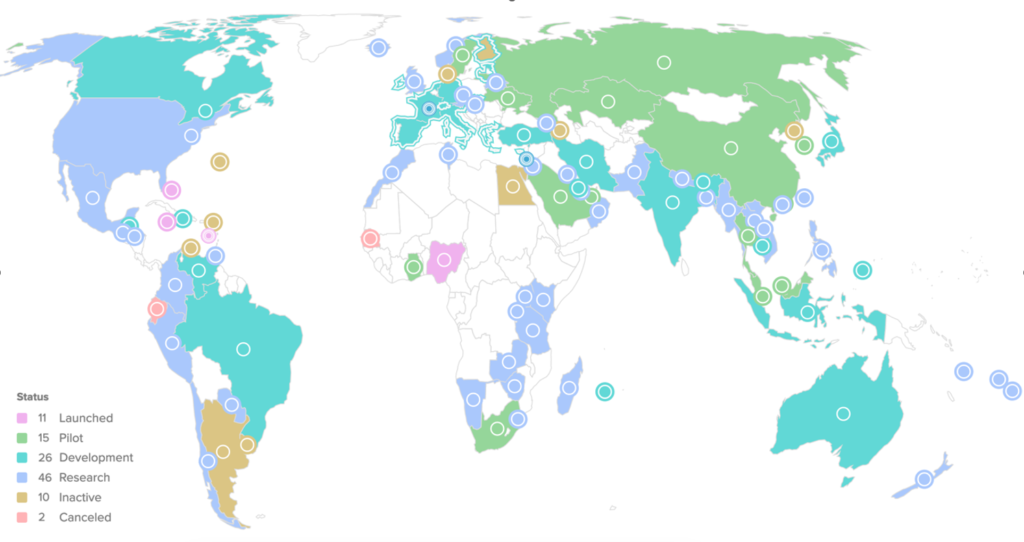

According to the Atlantic Council’s CBDC tracker, 11 countries have issued a CBDC for widespread retail or wholesale use, 15 have initiated small-scale testing of a CBDC in the real world with a limited number of participants, 26 have initiated technical build, and early testing in controlled environments, and 46 have established working groups to explore the use cases, impact, and feasibility of a CBDC.

A CBDC is not the same as a cryptocurrency or cryptoassets. Cryptocurrencies have gained greater prominence mainly due to unrealistically high bitcoin valuations and significant past gains made through altcoin trades. However, the valuations of these high-risk, high-return coins remain speculative and have caused many cryptocurrency holders to lose large sums of money in recent times. Unlike cryptocurrencies, a CBDC issued by a central bank is reliable, stable, not volatile, and could act as both a liquid and safe settlement asset.

The question is why central banks need to issue digital currency when they have licensed private entities to issue e-money. Prima facie central banks want to keep pace with the changing dynamics in the modern financial world, improve payment systems and be ready for the digital future. However, the reasons could vary based on the economic situation of different countries. For instance, some countries see CBDCs as a means to increase financial inclusion; for others, it is a path to increase competition and efficiencies in digital payment infrastructure. Policymakers argue that while CBDC may seem like e-money, there are subtle differences in liability and user trust. (Technical capabilities are out of the scope of this blog).

- A CBDC is issued directly by a central bank, while e-money is issued by a private entity (an e-money issuer) licensed by the central bank.

- Whereas the central bank is directly liable for the CBDC, the liability of the e-money is on the issuer.

- The issuer of the e-money is required to safeguard the funds, whereas the issuer of CBDC (the central bank) is not.

- As a CBDC is the digital form of notes and coins, it is denominated in the national unit of account, while this does not apply to e-money.

Alike e-money, CBDCs also have real-life use cases. For instance, CBDCs could be used to make person-to-person payments, merchant payments, international remittances, and government payments etc. However, the following policy considerations are crucial to the success of CBDCs and to ensure they co-exist fairly with other payment instruments.

National financial inclusion policy objectives

CBDCs could increase financial inclusion through network effects. However, in countries with limited or no official ID documents for KYC, central banks may need to cap CBDC transaction values and account balances, similar to e-money. CBDCs will likely face many of the same barriers to adoption and usage as mobile money, therefore, it is unclear how CBDCs would add value above and beyond mobile money’s contributions to financial inclusion.

The trade-off between the cost of national risk assessment and financial inclusion

Central banks will need to monitor the CBDC transactions for fraud, money laundering, terrorism and proliferation financing. Some central banks may partner with an independent CBDC wallet provider, in which case that provider could be responsible for transaction monitoring. In either case, there will be costs to monitor transactions and where a partnership with an independent wallet provider is involved, there will be additional revenue margins that the provider will charge on top. The situation could be complicated where balance and transaction caps are implemented to manage risks. CBDC transactions could become more expensive for users. To avoid these additional costs being passed on to the end users and achieve national financial inclusion policies, it is yet to be seen whether governments will subsidise or otherwise incentivise the use of CBCDs. Such a subsidy could lead to unfair competition unless given to all digital money providers.

Managing systemic risks and ensuring resilience

Central banks need to ensure the safety and resilience of payment systems. There is currently no evidence to suggest that mobile money poses a systemic risk to the financial system. However, considering the potential widespread adoption of CBDCs as a national digital currency, safeguards would need to be built to mitigate the risks of CBDCs leading to systemic failure. The G7 Central Banks are exploring the opportunities, challenges, and monetary and financial stability implications of CBDCs and are committed to working together to overcome such risks.

Fair treatment of consumers

Mobile money providers and electronic money issuers manage customer service aspects of the business when offering digital money services. A concern arises whether the central banks have the resources to handle this function and provide recourse and redress mechanisms to the public on a large scale. Even if this function is outsourced, for instance, when partnering with an independent wallet provider, fair treatment of consumers should remain a top priority, and the central bank will still need to develop clear consumer protection guidelines, including recourse mechanisms.

Data privacy

Rigorous data privacy standards and accountability for data protection will be essential to build consumer trust and confidence in CBDCs. Central banks can build solid safeguards for domestic CBDC payments. Still, there are concerns about how this would work in practice when data is required to be shared across jurisdictions, for instance, when making international CBDC payments. Central banks may use the G7 roadmap for cooperation on data-free flow with trust as they develop safeguards for cross-border CBDC data flows.

Interoperability policy

Interoperability with domestic and international payment systems remains crucial in the successful rollout of CBDCs. While many central banks favour interoperability as a building block for sustainable CBDCs, it must be recognised that interoperability has associated costs. How central banks will implement and regulate this effectively in markets where digital money, such as e-money and payment cards, already exist, is yet to be seen.

Independence and Impartiality

Concerns about the central bank’s independence and impartiality as a financial services regulator and an issuer of CBDC while competing with other digital money issuers would need to be addressed. Issuing digital money must not impede the central bank’s ability to fulfil its primary mandate. It is unclear how central banks would perform the dual role under the current organisational structure.

In conclusion, CBDCs present opportunities for responsible innovation in the digital finance ecosystem, albeit as a competitor to other forms of digital money. As issuers of CBDCs, the central banks are in an enviably powerful position. Despite this, they must ensure a level playing field and promote enabling regulations and policies for the market to thrive. The central banks should promote collaboration, openness and trust among public and private players and encourage innovation in the digital money ecosystem. By doing this, they will build a resilient financial system where CBDCs, mobile money, e-money and other forms of digital money can co-exist and thrive.

Coming up: The GSMA plans to publish further insights on CBDCs and recommendations for mobile money providers in 2023.