The GSMA AgriTech programme, in partnership with a consortium of local partners, supported the launch of a loan service – Rural loan – for vanilla farmers in Papua New Guinea (PNG) with the support from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

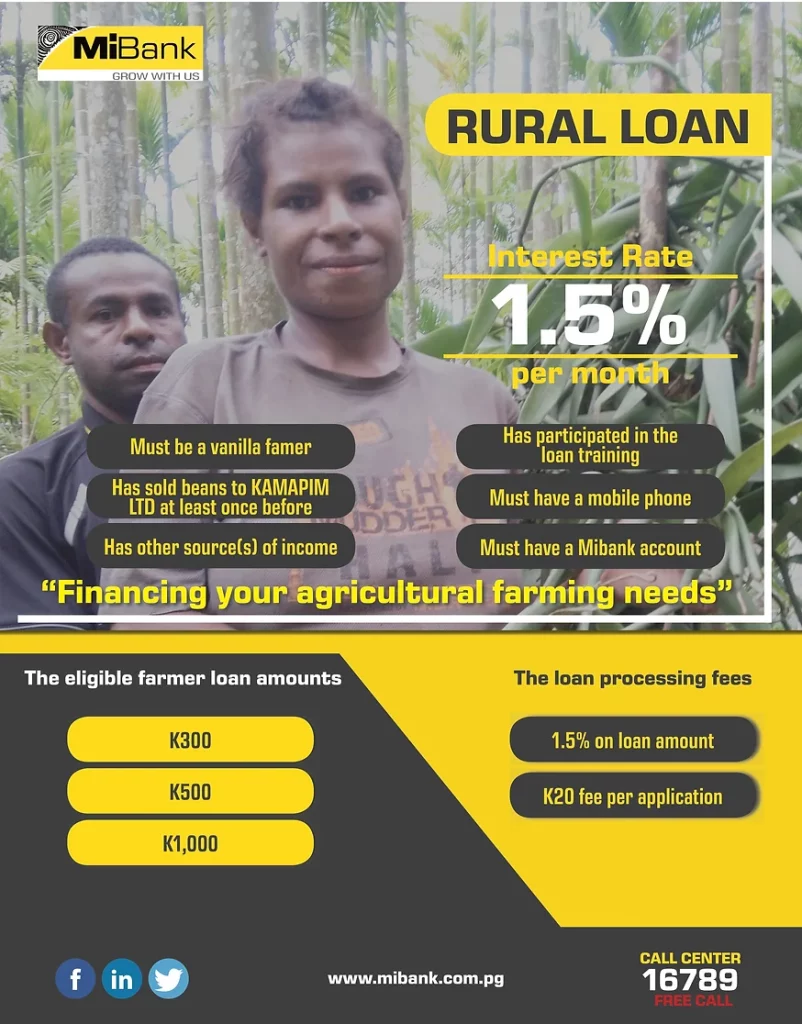

Promotional material from Mibank, 2021

Based on User Experience research on farmer credit needs, the loans were designed around three ticket sizes: PGK 300, PGK 500, and PGK 1,000 (approximatively GBP 69 to GBP 230). Service delivery relied on a partnership between MiBank, the largest microfinance bank in PNG and Kamapim, a vanilla-buying agribusiness that had existing procurement relationships with vanilla farmers. The pilot disbursed 355 loans to 330 farmers over 2.5 years, of which 35% were women.

We conducted in-person interviews with 23 farmers from the Sumkar District and Middle Ramu in Madang Province to gain first-hand farmer feedback on the Rural loan service and explore whether the pilot had a positive contribution on smallholders’ financial inclusion and financial literacy.

Leveraging established trust within formal relationships between farmers and procurement agents is key to achieve farmer trust and buy-in

Farmers expressed very positive feedback on loans, including on the bank account opening and loan application processes, which heavily relied on trusted agents from the agribusiness Kamapim.

“The process of opening an account was very easy, Kamapim employees were very helpful to us. They understand that some of us don’t have that modern knowledge to do it, they did everything for us.”

They valued time savings from being able to apply for loans in their village, instead of having to travel several hours to Madang City due to poor road infrastructure and travel times often worsened by weather events, in addition to the instant loan approval feature.

All interviewed farmers said they would recommend this loan service to other farmers.

“Kamapim brought the bank workers and simplified the processes for us, this loan scheme is a great service for our people. It is like they brought money into our community. Rather than going to town to access financial services, we could do this right where we are.”

Introducing loans in small farming communities requires clear, consistent loan terms and alignment with crop cycles.

Knowledge about differential treatment will circulate among farmers and can lead to frustrations. For example, farmers indicated that they would prefer to have consistent repayment periods for all farmers such as a specific number of months, starting from the moment they take up a loan, rather than a fixed due date regardless of when the loan was taken. Reasons behind lower ticket sizes or loan repayment timelines should be clearly communicated with farmers to provide transparency and buy-in.

Launching agricultural loans that aim to improve farmer productivity requires carefully planned roll-out that is aligned with sowing and harvesting times during which farmers have financing needs for tools, inputs or labour. Repayment times should also match crop harvest and selling cycles. Otherwise, farmers might struggle to repay loans until they receive payments for their harvest.

“The period of repayment is not long enough for some of us. Vanilla is a seasonal crop therefore we have to look for other alternative ways to repay the loan on time.”

Piloting loans in value chains with continuous or multiple harvests is a key opportunity to explore for financial service providers, as farmers will have more frequent agriculture-related financing needs and more regular income with which to repay loans.

Almost all (99%) of farmers gained first-time access to loans and used them to purchase farming tools, hire labour or start complementary revenue-generating activities

Among farmers interviewed, only two had a bank account previous to the project and one had obtained a formal loan. This project helped farmers get first-time access to bank accounts and loan services and saw an appetite among farmers to apply for further loans, which indicates a clear contribution to financial inclusion. Overall, the loans met their intended purpose, with farmers using them to purchase grass knives and hire labour to pick, clean and pollinate vanilla pods.

“In the past I would not actively work in the farm and since I got a loan, I am now actively growing, harvesting, and selling in the markets so that I could earn more money to repay my loan on time. By repaying on time, I will have a good record with the bank, and this will allow me to apply for more loans in the future.”

“It [the loan] helped me buy my new tools and expand my vanilla farm from 300 plants to 1,000 plants.”

Many farmers also used the loans to engage in complementary income-generating activities to supplement farm income, such as buying store goods in town to resell in the community. Finally, remaining loan amounts were used for other household needs, such as paying for children school fees or purchasing medicine or food, indicating that loans helped farmers with low cash flows before the harvest season and benefited the wider household well-being.

Farmers, many of whom had never had a bank account, improved their awareness of loans and showed positive attitudes towards financial services.

User Experience research conducted during the initial product design stages confirmed that the target user segment showed low levels of financial literacy, therefore farmers who applied for loans were required to join trainings designed to build their knowledge on loans. As a result, the project led to improvements in the different dimensions of financial literacy[1], including awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours. Farmers demonstrated a clear understanding of loan terms and associated risks for defaulting. Farmers showed a clear willingness to repay the loans and timely repayments were perceived as key to building a good record with the bank. These improvements are particularly significant since the vast majority of farmers were opening a bank account for the first time.

“It’s a new experience for me. I want to maintain a good record with the bank so when I return for more loan, I already have a good history with them.”

Farmers showed a positive attitude toward the loan service, mentioning trust and a clear understanding of its value proposition. All farmers demonstrated that they knew how to repay their loans. However, we found that most farmers lacked the confidence to apply for loans by themselves without the help of Kamapim agents or bank staff. While agent-led loan applications made the process convenient for farmers, teaching them how to replicate the process independently will be critical to further build their financial literacy and scale the service at low cost. Trainings on financial literacy are very much in demand by farmers, and introducing easy to understand step-by-step guides on how to apply for loans will be key to empower first-time loan users to apply to future loans.

“For individual farmers, having a cash flow plan for each one of them is necessary. Financial literacy is a key priority for our people because money is not part of our culture. It is a ‘white man’ (foreign) concept and therefore education regarding its management would help us greatly.”

Conclusion

This promising loan pilot showed positive farmer feedback and confirmed the high demand for loans among smallholders. Farmers with first-time access to bank accounts and loans can develop trust in financial services, show a clear understanding of loan repayment terms and see the service’s value proposition. Farmers used loans to improve their farming, start complementary revenue-generating activities or make purchases while their cash flow is low between harvest seasons. For replicability, we recommend that future loan-related projects be launched in partnership with an agribusiness or cooperative, involve substantial financial literacy trainings and align loan repayments with crop cycles.

Download The GSMA AgriTech Toolkit for the digitisation of agricultural value chains for a comprehensive guide on launching digital agricultural services.

To gain a deeper understanding of GSMA’s activities in Papua New Guinea aimed at enabling access to credit for farmers, please contact the GSMA AgriTech team at [email protected] to join the discussion.

[1] For more details on the dimensions of financial literacy, see OECD. (2021). PISA 2021 Financial Literacy Analytical and Assessment Framework.