A question we get asked a lot at the Digital Utilities programme is: When are we going to see the Uber for water? This question points to two things. First, that in many peoples’ minds digitalisation has become synonymous with the deployment of digital platforms. Second, that the general perception is that utility services have yet to receive the ‘Uber’ treatment.

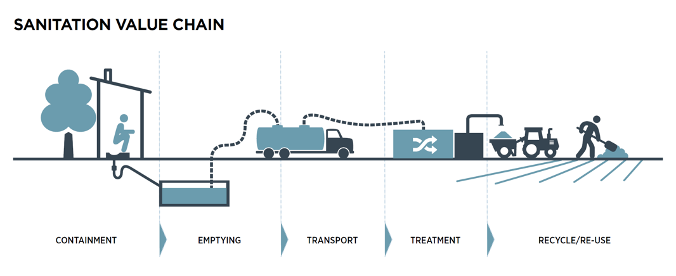

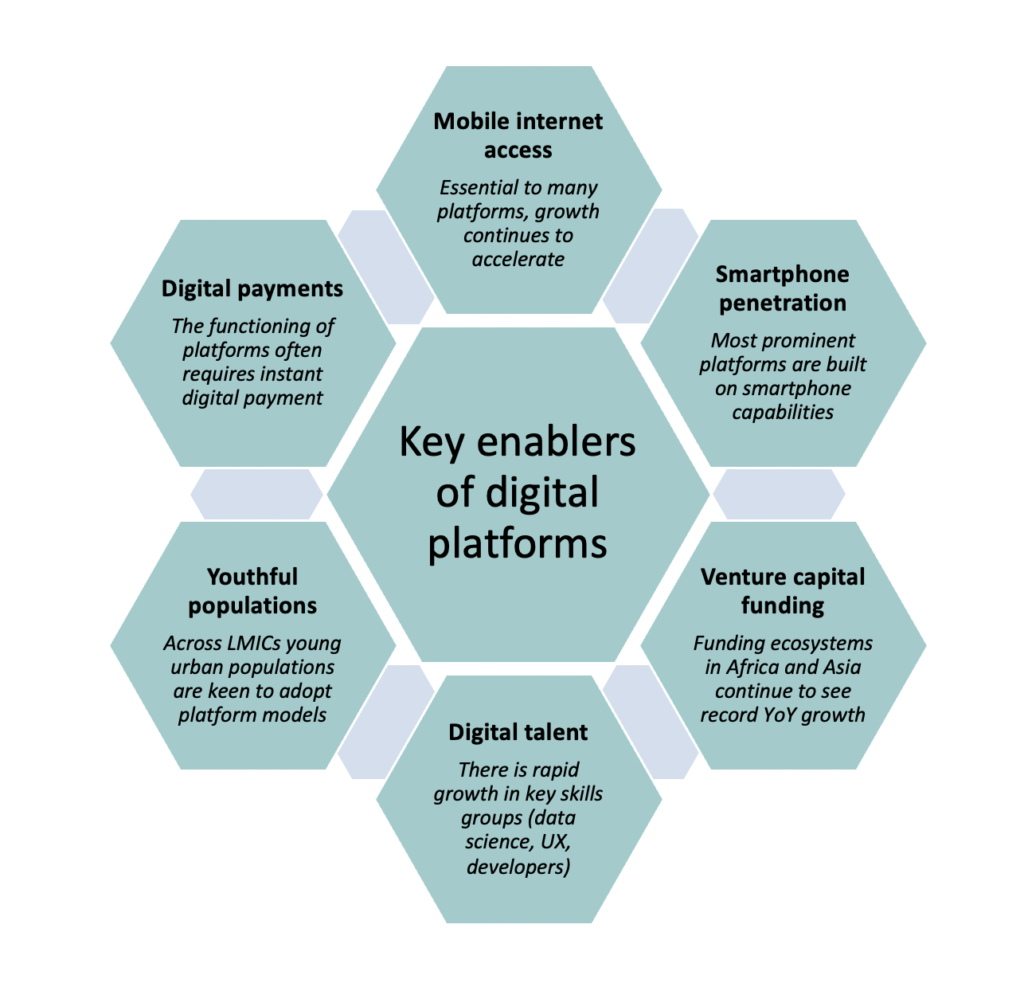

Platform models are gaining traction, and attracting significant funding, across many low- and middle-income country (LMIC) markets, and there’s increasing attention on their applicability for essential utility services. The figure below highlights some of the key enablers of this identified in our past research. The market dynamics in the utility sectors – energy, water, sanitation, and waste management – shape how these platforms can be deployed, and where value can be generated. There are also some questions surrounding the desirability of the ‘platformisation’ of services that are a human right.

Source: GSMA (2021), Scaling digital platforms through partnerships: The value of collaboration between mobile operators and digital platforms in emerging economies

This blog provides a general overview of the market dynamics in key utility sectors, reflects on what this implies for the use of digital platforms, looks at some of the emerging examples of platform models we have seen deployed in the utilities sector, and considers how we might see these scale in the coming years.

What do we mean by a platform?

Understanding of what a platform is varies, and on the whole there isn’t a widely agreed upon definition for what can be quite different solutions. For the purposes of this blog, we follow the definition used in our recent report on scaling digital platforms, that is:

“technology-enabled business models that create value by facilitating exchanges between two or more interdependent groups”

This is a broad definition, but importantly excludes certain types of platforms. For example, in this blog we are explicitly not considering platforms that focus only on aggregating and presenting data (e.g. dashboards or data management systems). These are widely used in the utilities sectors, and are valuable, but are not the focus of this blog.

Instead, the definition draws attention to platforms that generate value by facilitating exchange, and focuses us towards market-creating innovations. Some examples of these types of platforms are below.

- e-commerce marketplaces – e.g. Jumia; Daraz, Alibaba, Amazon

- Marketplaces with sector-specific value-add features – e.g. Twiga, mPharma, Kobo360, Halodoc, Ninjavan, Uber

- Payment platforms – e.g. Mobile Money (such as MTN MoMo, M-Pesa), Paga, Paystack

- Customer relationship management platforms – e.g. Angaza, Salesforce

- Super apps’, single platforms that offer a wide range of different goods and services, often with financial service offerings – e.g. Grab, Gojek, Gozem

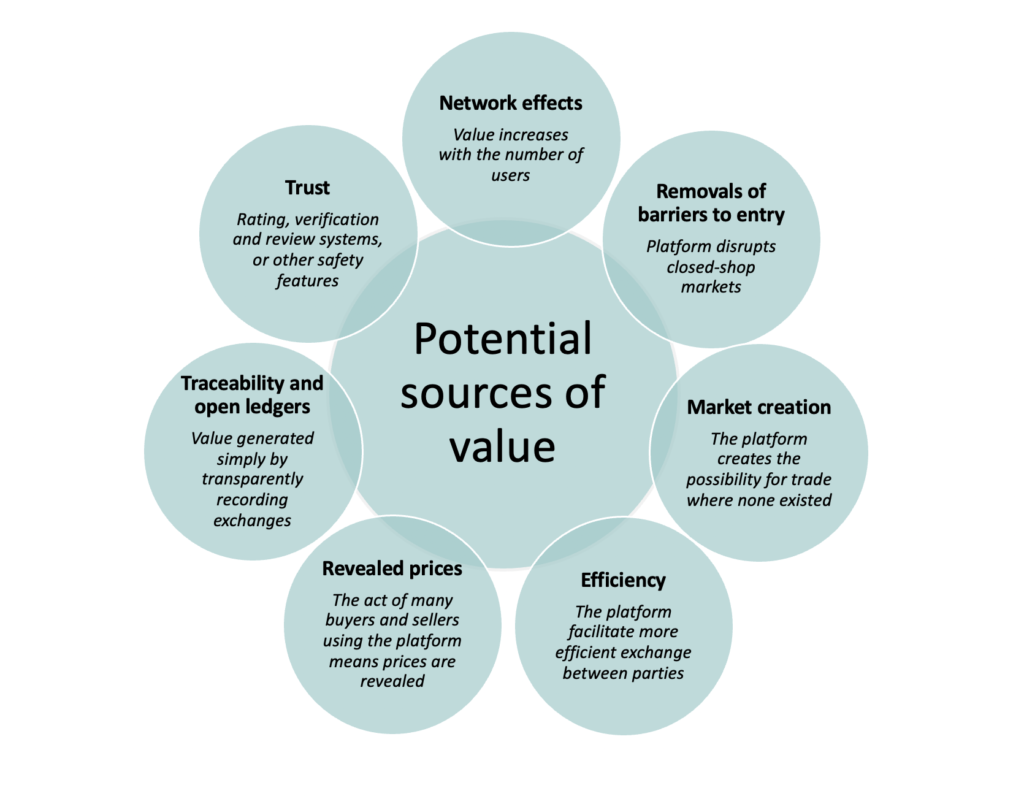

The figure below outlines some of the potential sources of value for different digital platforms in the utility sectors. While we don’t discuss them in this blog, we also recognise that platforms can have some downsides, particularly in cases where a player has excessive market power, and some of the risks associated with the casualization of work and the proliferation of the gig economy. Considering these sources of value, as well as the risks, is essential to conceptualising how and where platforms might fit across the different utility services.

Source: Author’s own design

Deploying platforms, the impacts of differing market characteristics

The extent to which a platform can deliver value, in line with the definition used above, is highly dependent on the market characteristics in which they operate. Most significantly for platform models, the number of buyers and sellers.

In some of the utilities sectors, services can be dependent on large and highly centralised infrastructure networks. For example, large urban water networks, or a national electricity grids, are textbook cases of ‘natural monopolies’. That is, where the extent of the need for large integrated networks means that monopoly provision, with effective price controls, can in some circumstances be the most efficient way to deploy and run services.

While this is the case for centralised water and energy services, this thinking does not apply to all service models in those sectors, or mean that within those sectors there isn’t scope for digital platforms. Off-grid services across all the utility sectors, as well as along different parts in fragmented value-chains can be where platforms find their niche.

For example, while piped water provision suits a centralised service model, the distribution part of the water value chain can be a very competitive market. With many private, informal, or community based vendors focusing the final stage. Additionally, in many low- and middle-income countries, waste management and sanitation services are markets characterised by many independent, and often informal, workers. In these markets there is huge potential for digital platforms to generate value in connecting buyers and sellers, improving working conditions for those waste collectors, and ensuring this is done safely through tracing the waste.

Source: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

The figure below provides a very broad characterisation of how some utility services can be organised, based just on the dynamics of the number of buyers and sellers. This figure just seeks to highlight the potential differences between services. In reality this figure will look very different in different markets and cities depending on how services are organised and regulated.

Source: Author’s own design

What we are seeing in the different utilities sectors

Energy

Sector context

Generic sector value chain

Generation – Transmission – Distribution

Parts of the energy value chain suit centralised provision, most notably in transmission through a national grid. For large-scale power generation – e.g. large hydro project or nuclear – the barriers to entry can be very high as these are very capital intensive projects, and often rely on public sector co-financing.

What we are however seeing is that in off-grid energy there is scope for platforms to enable energy transfer between decentralised producers/consumers, and blur the line between on-grid and off-grid energy production and consumption. This, in part, is built on proliferation of solar systems and micro-grids, which themselves often have their service models built off of digital payment platforms.

Examples of emerging platforms

- Solshare is an example of an energy-specific trading platform. Solshare have created the first peer-to-peer energy trading network, having received a seed grant from the GSMA to pilot in 2015.

- Angaza is a great example of a CRM platform that has emerged with features designed specifically to meet the needs of companies working in challenging distribution settings.

- CaVEx is a platform currently in development that intends to disrupt the voluntary carbon market through opening it to smaller projects and players. The platform intends to enable businesses buying carbon credits to connect directly to smaller, verified, carbon reducing projects.

- Built on the back of success in PAYG solar we have seen some PAYG solar companies evolve their business model from focusing only on solar to becoming asset financing platforms, M-KOPA exemplify this evolution.

Water

Sector context

Generic sector value chain

Source extraction – Bulk supply & storage – Treatment – Distribution – Treatment & Disposal

As with energy many water service models are suited to centralised service delivery. However, value chain disaggregation, especially at the distribution stage is comparatively easier. While piped water services tend towards monopoly provision, there are more competitive markets for different services (tanker truck delivery, bottled water), and within the distribution part of the value chain.

In the case of utility provision, prices/tariffs are often highly regulated (and highly political). Prices outside utility provision are often the opposite and are unchecked. With price gouging at times of scarcity in less competitive market conditions well-documented (e.g. the ‘tanker-truck mafia’).The platforms that have emerged tend to focus on just the water treatment and distribution parts of the value chain, as this is where value can be generated from certifying the quality of water, and connecting vendors and customers and managing delivery.

Examples of emerging platforms

- Powwater is a platform for accrediting trusted vendors and arranging deliveries. The service includes verifying the quality of water. Powwater have recently launched in Kenya.

- JanaJal in India started by providing water through fixed water ATMs. Recently they have been developing their Water on Wheels (WOW) service. Customers can order water to their homes via an app or USSD menus, which is then delivered to their door by a modified auto rickshaw.

Sanitation

Sector context

Generic sector value chain

Faecal waste containment – Emptying – Transport – Treatment – Disposal or Reuse

In this sector there is often a big difference between sewered services (which rely on centralised infrastructure) and decentralised non-sewered services (which can contain more competitive markets). In many countries sewer coverage is relatively low, and the majority of people rely on onsite solutions or pit/septic tank emptying.

Pit-emptying and the transporting of faecal waste to treatment is, in many cases, a market characterised by many informal players. A key area where digital platforms can add value in sanitation is ensuring that waste is not illegally dumped, something that is extremely common in many markets, and creates public health risks and environmental degradation.

Examples of emerging platforms

- In 2015 the GSMA gave a grant to the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) to develop and deploy a platform that can be used to organise and track waste emptying services in the city; and

- iCesspool, launched in Ghana, is a platform for arranging and monitoring septic tank emptying services. Customers can order via the app from independent providers, iCesspool then monitors the providers to ensure the waste is safely disposed of and not indiscriminately dumped.

Waste management

Sector context

Generic sector value chain

Collection – Transportation – Processing/Recycling – Disposal or Reuse

In waste management there are often many buyers and sellers in the collection part of the value chain, these can be highly competitive and informal markets. Whereas the processing and disposal stages are less competitive parts of the value chain with fewer, and more centralised, facilities. As with sanitation, it is within specific parts of the value chain that platforms can really add value in waste management.

Additionally, for waste management there is huge value in ensuring that the movement and disposal of waste is accurately and openly tracked. Not least as this can help ensure that, as part of extended producer responsibility (ERP) policies, companies can be certain their waste is being responsibly disposed of. Many companies also put effort into ensuring that their services ensure that the workers (waste pickers) can work in improved conditions.

Examples of emerging platforms

- Octopus in Indonesia is a is a circular economy platform that help producers to track & collect post-consumer products, verifying waste providers to support EPR strategies.

- Coliba in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire is the first African Mobile app designed to manage plastic waste. Through a franchise model, waste pickers are integrated into a digital platform that enables homes, institutions and communities start and request recycling services.

- ReCircle are a similar platform in India. Their platform tracks the collection and recycling of plastics, minting credits for the waste recycled. Business partners participating can then be sure they are complying with ERP responsibilities.

What we might see in the future

Digital platforms undoubtedly have a place in utility services, the question is where they fit within each sector, and being clear about the value they can generate. That all of the utility services are essential to the functioning of cities mean, of course, there is a huge potential market. And at present many people – particularly those in informal settlements – are simply not being served with safe, affordable, and reliable services. There is a real need for disruptive innovations.

On the face of it some of the market conditions within some utility sectors (esp. water and energy) aren’t particularly ripe for the ‘Uber’ treatment. There also a natural limit to how far these platforms can scale as utility services are so often tied to infrastructure and fixed geographical areas. Yet, niche platforms with a clear sector-specific value add may be able to branch out across similar service areas or markets, or find their place within super-app offerings.

In the service models discussed above there is often a dichotomy between centralised and de-centralised service delivery. Digital platforms have the potential to blur this line through bringing informal and formal providers close together. Particularly in cases where platforms generate value through:

- Guaranteeing the standards of a service for customers (e.g. water quality),

- Ensuring that regulation is complied with (e.g. safe waste disposal and ERP policies),

- Where network effects and crowd sourcing open the door to new production models (e.g. many small systems selling to broader networks), and

- In connecting customers to accredited providers (e.g. verified sanitation providers).

We’re excited to see what will come next for the emerging platforms discussed, and for those in the next cohort of GSMA Innovation Fund start-ups that have been announced.

The Digital Utilities programme is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and supported by the GSMA and its members.