When someone is born with or develops an impairing condition, they often face barriers impeding their participation in society which results in their disability. Assistive technologies (ATs) are products, services and systems that can help persons with disabilities to live independently and with dignity, such as wheelchairs, hearing aids and eye glasses. ATs help tackle some of the social and physical barriers that persons with disabilities encounter but, according to the World Health Organization, more than 90 per cent of persons who need assistive technologies do not have access to one.

From the one billion people in the world that are estimated to have some form of disability, the majority live in a low- or middle-income country with limited access to high-quality and affordable ATs. This is because most ATs have been designed to serve high-income markets, and technologies prove to be dysfunctional when reaching a lower-income setting.

Mobile has the potential to serve as an AT in underserved markets

The affordability, portability and versatility of a mobile’s functions have led to their ubiquity in many contexts where other technologies have hardly reached. In places where access to ATs is limited, some of the functions of mobiles can bridge the gap in access to supporting products and services for persons with disabilities.

Due to the lack of data and research, it is difficult to know to what extent are mobiles acting as ATs and what their enabling capabilities are for the inclusion of persons with disabilities. For this reason, we decided to conduct research on the characteristics of mobile ownership, access and use amongst persons with disabilities in Kenya and Bangladesh. Here are some of our key insights:

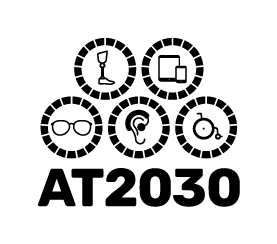

Persons with disabilities are less likely than non-disabled persons to own a phone

The surveys found that 82 per cent of persons with disabilities in Kenya and 62 per cent of them in Bangladesh own a mobile phone. Although these proportions are relatively high, they are lower than those for non-disabled persons in each country. Our research found a mobile disability gap in ownership of over 12 per cent in both countries.

Some non-owners borrow mobiles from relatives, friends or family members. This includes 14 per cent of persons with disabilities in Kenya and 25 per cent in Bangladesh. While this allows them to gain access to a communication tool and connectivity, they are often restricted on how they can use the phone.

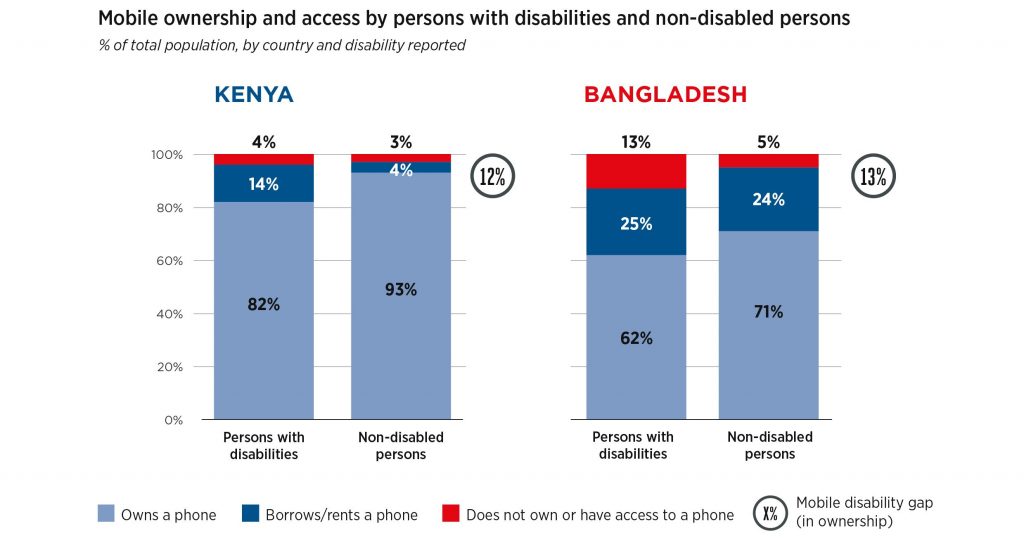

Smartphone ownership remains limited for persons with disabilities

The type of mobile owned can be important for some persons with disabilities. In each country, more than 70 per cent of persons with disabilities own either a basic or a feature phone. While in Kenya there is only a four per cent difference in smartphone ownership between non-disabled persons and persons with disabilities, more persons with disabilities own a basic phone than non-disabled owners. In contrast, in Bangladesh a similar proportion of non-disabled owners and owners with disabilities have a basic phone, but many more non-disabled persons own a smartphone compared to persons with disabilities.

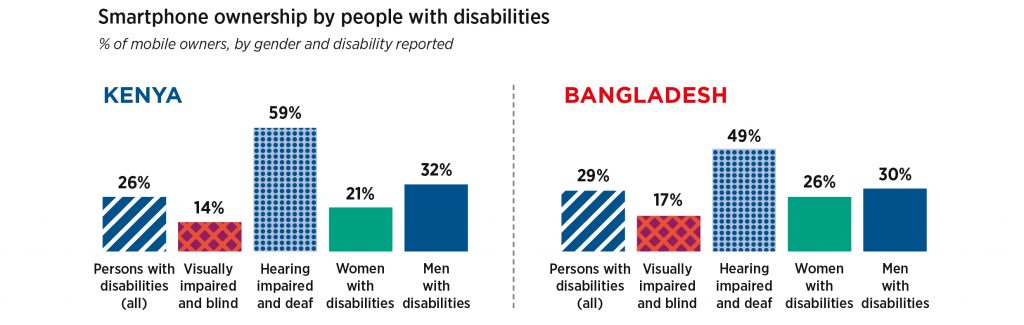

There are also differences in the type of mobile owned when disaggregating the group of mobile owners by type of disability. Representing less than a third of persons with disabilities in each country, around 50 per cent of customers with hearing impairment or deaf have a smartphone. This is a high proportion in comparison to the 14 per cent of visually impaired owners in Kenya and 17 per cent in Bangladesh.

Just as the type of disability, gender seems to be a relevant factor for smartphone ownership amongst persons with disabilities. Women with disabilities are less likely to own a smartphone than men with disabilities. In Kenya 21 per cent of women with disabilities own a smartphone and the gender gap in ownership by persons with disabilities is 34 per cent. This gap is smaller in Bangladesh, 13 per cent, where the proportion of women with disabilities that own a smartphone is similar to men with disabilities.

We need to talk about accessibility

One of the advantages of smartphone ownership for persons with disabilities is the possibility to access and use accessibility features. Accessibility features are functions that facilitate the use of mobile and improve user experience. Accessibility features include functions such as digital text magnifiers, speech-to-text and text-to-speech technology, voice command and adjustments for hearing aids.

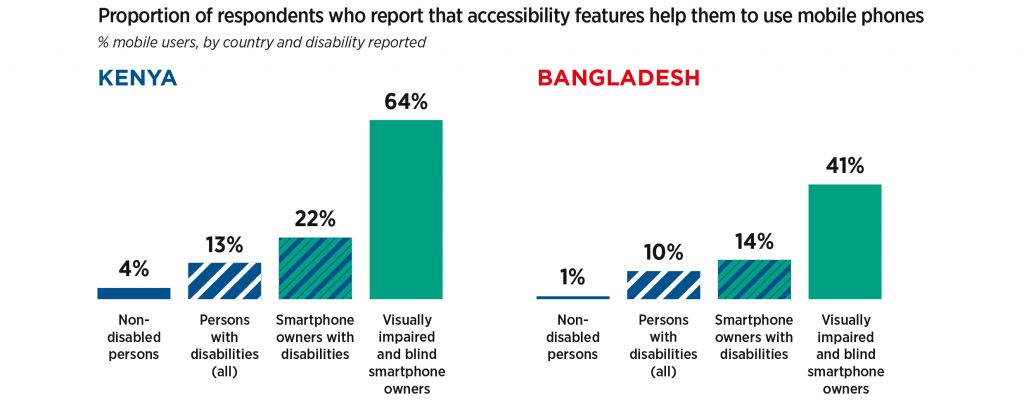

Although the use of accessibility features can totally change the experience of the users, our research found that only around 10 per cent of persons with disabilities use them. In fact, even when looking at the proportion of smartphone owners with disabilities, only 22 per cent in Kenya and 14 per cent in Bangladesh reported to use accessibility features. While visually impaired users are the least likely to own a smartphone, they are highly benefiting from the functions provided by this type of phone and have a much higher usage of these features than other smartphone users.

Challenges across the customer journey

Even if mobile ownership is high and higher end phones have relevant accessibility functions for persons with disabilities, challenges were reported through the different stages of their use of mobile. Firstly, many persons with disabilities and their relatives do not know about relevant accessible products. Secondly, the most accessible handsets are unaffordable to most persons with disabilities and, often, the cost of services can be restrictive, limiting the potential that mobile could have in supporting their daily tasks. Finally, many persons with disabilities report not owning a phone or using services due to a lack of knowledge on how to use them.

Closing the mobile disability gap

This report is a first step to building our knowledge of the existing digital inclusion gap for persons with disabilities in emerging markets. To address this gap, the GSMA Assistive Tech programme will engage with mobile operators to find ways in which mobile products and services can improve digital inclusion. By sharing the individual stories of persons with disabilities in their daily mobile user experience, we hope to raise awareness about the impact mobile can have as assistive solutions and why the mobile industry has an important role to play.