According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, more than 3 billion people – almost half of the world’s population – live in rural areas, and roughly 2.5 billion people depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. Supporting smallholder farmers is therefore seen as critical to achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and reducing poverty, hunger, malnutrition and inequality. The GSMA mAgri programme has also collected a wide body of evidence which shows that advancing the productivity and profitability of farmers – and the agricultural industry at large – presents a significant opportunity for mobile network operators (MNOs) across much of the developing world.

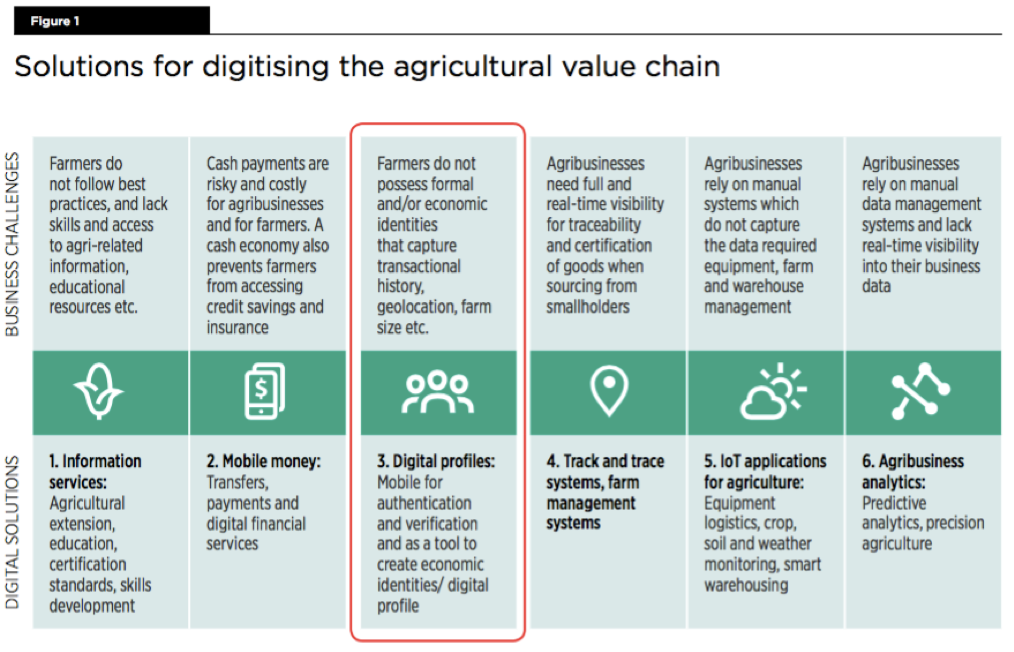

The rural poor are one of the least likely demographics to have access to an official proof of identity, which is increasingly essential to securing access to mobile connectivity, financial services and social protections. Even where identity coverage is widespread, a tension exists between a farmer’s ‘fixed identity’ (i.e. the demographic and biometric details recorded on their identity document), and their more fluid ‘economic identity’, which accounts for their shifting, dynamic social and economic circumstances. Farmers who are unable to prove their creditworthiness or validate other vital credentials (for example, income and transaction histories, ownership of land, crop types, geo- location or farm size) are more likely to face barriers accessing formal services or connecting to the global economy. For this reason, the GSMA has identified ‘digital profiles’ as one of the key bottlenecks, and opportunities, for digitising the agricultural value chain.

In our newest report, the Digital Identity programme highlights key findings from our qualitative research in Sri Lanka, which was designed to improve the mobile industry’s understanding of farmers’ identity-related needs and pain points, as well as their attitudes and perceptions towards digital identity. The research also allowed us to explore how agribusinesses and other service providers (e.g. MNOs, financial service providers) could gather and/or authenticate digital information for farmers in order to help them build robust and recognised ‘economic identities’. The research builds on our programme’s end user research from early 2017, and the mAgri team’s recent analysis of Dialog Sri Lanka’s Govi Muthuru service.

After spending a couple of weeks in Sri Lanka, it was easy for us to understand why the country has earned nicknames like ‘Resplendent Isle’ and ‘Pearl of the Orient’. It is a beautiful and pleasant place to live, and most of the farmers participating in our research were very happy with their profession and the local lives they lead. In recent years Sri Lanka has made great strides in reducing poverty, gender disparities and income inequality, and despite facing various challenges in their profession, our research found that farmers enjoyed good access to local government services, good local provision of agricultural support, and good rural infrastructure. Sri Lanka is also a market in which formal identity documents are robust, widely-accepted, and valued by users; official proof of identification is ubiquitous and easy to acquire, even in rural areas.

Even so, changing contexts are creating new needs and pain points for farmers. Most farmers’ access to information and support is deficient, and there is also significant scope to improve financial access and inclusion for farmers by enabling greater access to a broader range of affordable and relevant financial services such as mobile money, digital payments, credit and insurance. Our report highlights a number of important cross-cutting themes that are likely to shape the opportunity for identity solutions in Sri Lanka, as well as other emerging markets.

These can be summarised as:

1) Identity needs vary by farmer type: A farmer’s identity-related needs and priorities can be influenced by a wide range of factors, including the types of crops they grow, their age and the social capital they possess. It will be important for service providers to take a targeted approach when designing digital identity solutions for this diverse population.

2) Identity documents have both practical and emotional value: Farmers overwhelmingly agreed that there would be value in possessing a proof of identity that enabled others to recognise their status as successful ‘cultivators’ and ‘producers’ – this could facilitate easier access to formal services and also build pride in their profession.

3) Face-to-face relationships are vital: In the close-knit rural communities where farmers live, informal networks and social forms of identity such as reputation are vitally important. Service providers seeking to implement digital identity solutions will need to provide personal, accessible touchpoints in order to build trusted relationships with farmers and help them navigate services and support.

4) The agricultural landscape is changing: New influences such as climate change and the globalisation of agricultural markets are creating new challenges and opportunities for farmers. Traditional, inherited knowledge is losing some of its practical value, and digital identity solutions that help farmers establish new forms of connection and access relevant information will be meaningful.

From our research, it is clear that digital identities have the potential to help farmers build pride in their profession, feel more informed, connect to new markets or buyers, access digital financial service and reduce their financial risk. In the long-term, this will help lead to improved farming practices, increased digital and financial inclusion, and higher productivity. For MNOs, digital identities could act as a key enabler for digitising the agricultural value chain and extending a wide range of services to rural users and enterprise customers. In 2018 the Digital Identity team hopes to build on our understanding of farmers’ identity needs and opportunities, and we are starting to explore how to leverage these new learnings to help partners in Ghana create better services for farmers. Be sure to check back with us throughout the year to see what we’re learning.

This initiative is currently funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), and supported by the GSMA and its members.