We would like to thank Susan Smith, VP Finance Solution, Public Sector at Odyssey, for her input on this blog.

Results-based financing (RBF) is a development financing and public policy approach that seeks to link payments to the achievement of specific results or outcomes. The approach has been applied to promoting outcomes in a range of sectors including education, health, water, sanitation and energy.

After providing a brief overview of RBF, this blog focuses on the role that Internet of Things (IoT) solutions and digital payments have in overcoming common design and operational challenges associated with RBF, and how they can enable RBF programmes to operate at greater scale across use cases. It also highlights what digitally enabled RBF programmes mean in practice by illustrating Odyssey’s collaboration with Nigeria’s Rural Electrification agency under the Nigeria Electrification Project.

An introduction to RBF

RBF approaches generally have some common core elements:

- Payments are made based on a set of pre-agreed results

- Implementing partners have flexibility on how results are achieved

- Independent verification of pre-agreed results

- Suppliers take on a greater portion of the risk as they are accountable for the results

While RBF approaches have been used as public policy-making tools across multiple countries for several decades (performance-based incentives for education or mechanisms to overcome the high per connection costs associated with rural electrification), RBF as a term in the global development context emerged in the early 2010s, promoted notably by the Centre for Global Development under the name ‘Cash on Delivery Aid’, and DFID under the name ‘Payment by Results’. The Global Partnership for Results-Based Approaches (GPRBA) have a useful summary of some of the different financing instruments that fit under the RBF umbrella.

Figure 1: RBF mechanisms

On paper, these RBF approaches have multiple advantages and can help drive development financing transparently and deliberately. They include:

- Focus on outcomes: RBF programmes focus on achieving specific outcomes, rather than inputs or activities. This can lead to better performance, as the programs incentivise individuals and organisations to prioritise achieving these outcomes.

- Flexibility: By design, RBF programmes allow delivery partners to determine the way they achieve the outcomes/results. This can lead to innovation and creativity in problem-solving, as individuals and organisations are not constrained by rigid input- or activity-based targets.

- Accountability: RBF programmes have a clear link between funding and results, making it easier to hold stakeholders accountable for their performance.

- Improving resource allocation: RBF programmes can improve resource allocation by ensuring that funding is directed towards programmes that are achieving results.

- Incentivising collaboration: RBF programmes can incentivise collaboration between different stakeholders, as organisations are often required to work together to achieve the desired outcomes.

Despite these advantages, many argue that RBF as a development financing instrument has failed to live up to its potential. Implementation and design challenges have limited the amount of funding committed and deployed through RBF. The roll-out of RBF programmes is often hampered by lengthy design processes linked to difficulties in developing measurable indicators, establishing a reliable baseline, ensuring stakeholder participation, addressing logistical and pre-financing needs of potential suppliers, and adapting programme specifications to the local context. During implementation, common challenges include measuring results/verification, manging incentives, and ensuring accountability and transparency. Manual, time-intensive verification processes are one of the key reasons RBF programmes struggle to operate at scale and deliver payments rapidly. In many RBF programmes for energy access, funders have to hire Independent Verification Agencies to call and visit end users to verify connection claims (a process which can often delay payments to selected suppliers to up to a year). Finally, RBF programmes – which in many sectors essentially provide a price subsidy – often lack plans for continued funding after a programme closes. This can create uncertainty for participating suppliers and investors, limiting participation, and investment by the private sector.

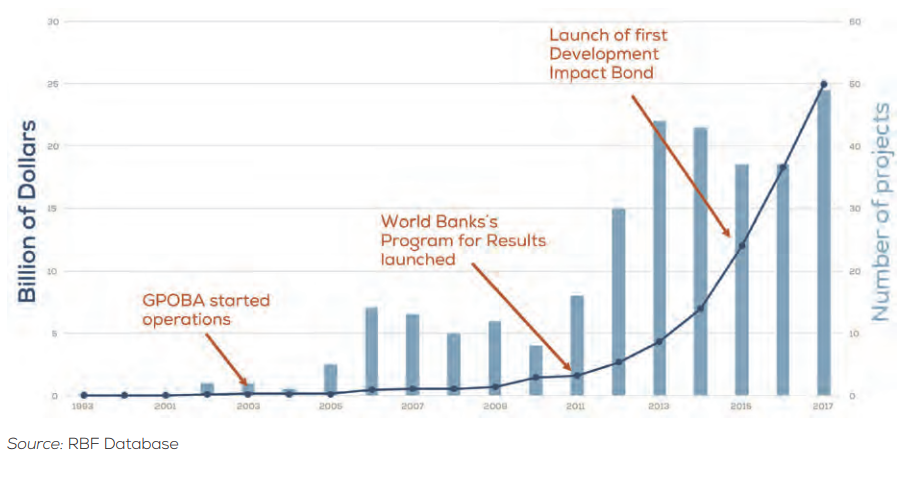

While RBF spending has risen substantially in recent years (see Figure 2), it still falls short of the funding gap for essential service delivery across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Overcoming the challenges associated with RBF could allow for programmes to deploy faster, operate at greater scale, provide more benefits to participating suppliers, and be applied to more use cases.

Figure 2: Cumulative Total of Spending Tied to Results through RBF, 1993-2017

At present, the use of RBF has been largely limited to a few sectors – predominantly health and education. Both health and education are sectors where monitoring is central to operations. Both sectors have also needed to distinguish between the quality of, and access to, services, and in both sectors employee behaviour (health worker/doctor or teacher) is a key determinant for outcomes. Other use cases such as extending energy/water/sanitation access also face large funding gaps that will not be addressed by private investment alone. Would these use cases also be able to benefit from RBF approaches? It depends – while some similarities do exist (access to energy does not mean access to reliable, affordable, sustainable energy), there are also important sector differences to consider (see this great review of the effectiveness of payment by results approaches in WASH).

In energy access in particular, there has been a realisation by donors, local governments, as well as the off-grid solar industry, that extending energy access in rural areas in LMICs requires subsidies (as has been the case in the broader global history of rural electrification). Therefore, RBF has become more central to rural electrification efforts and has become a core focus of rural electrification agencies across Africa and a wide range of donor-funded programmes such as Energising Development (EnDev), the Beyond the Grid Fund for Africa, the Universal Energy Facility, or the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme (ESMAP). Despite a broad coalition supporting the implementation of RBFs in energy access, the design and implementation challenges highlighted above prevent RBFs from being implemented at the speed and scale necessary to achieve SDG 7. For example, the African Mini-Grid Association highlights that the average time from announcement of RBF programmes to first deployment is often over three years in the sector.

The role of data and IoT in addressing common RBF programme challenges

The rise of mobile connectivity and digital innovation in LMICs – particularly digital payment ecosystems and cheaper and more reliable IoT systems and devices – has enabled the emergence of technological solutions that can help address some of the key challenges faced in RBF programmes (check out our recent report on IoT ecosystems in LMICs below).

These trends mean new possibilities for transparent, real-time remote verification at scale. In Figure 3, we highlight how IoT devices and digital payment records can address some of the key challenges associated with RBF:

Figure 3: How IoT helps address challenges faced by RBF programmes

Spotlight on Odyssey’s collaboration with Nigeria’s Rural Electrification Agency under the Nigeria Electrification Project

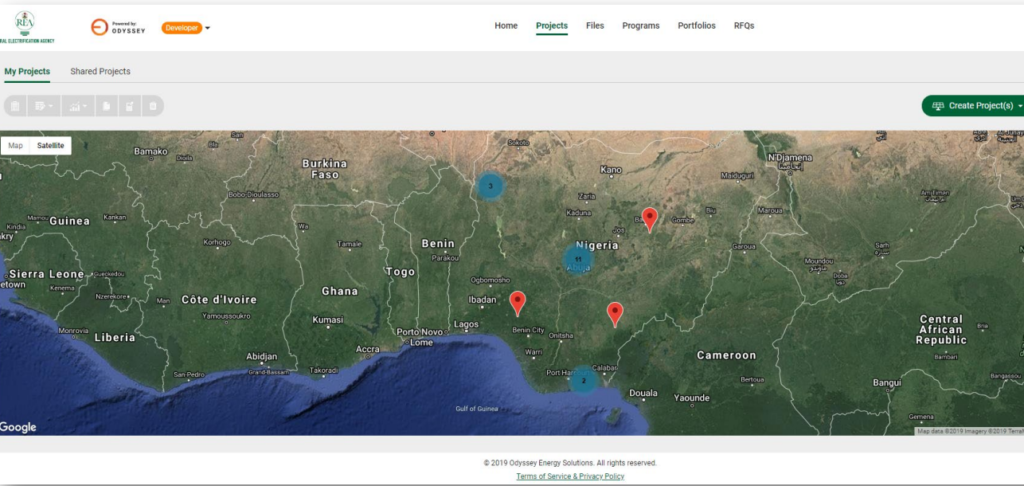

Odyssey’s end-to-end investment and asset management platform enables funders, governments, regulators and project developers to partner on mini-grid projects. Odyssey has worked on several electrification programmes across Africa and in Haiti.

In Nigeria, the country with the largest unelectrified population globally according to the International Energy Agency, Odyssey has been collaborating with the Rural Electrification Agency of Nigeria (REA) to deliver the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP).The NEP includes three results-based funding components: A mini-grid Minimum Subsidy Tender, a mini-grid Performance Based Grants facility, and a Solar Home System (SHS) Output Based Fund. Odyssey’s involvement in the programme centred on two major challenges: Baseline assessments and measuring results. Ahead of contracting, the REA needed to find a way to rapidly evaluate thousands of settlements for mini-grid development ahead of multiple large-scale tendering rounds. REA also needed an efficient way to develop robust baseline metrics to attract interest in the tender and assess complex technical and financial plans for project development by bidding service providers. The second challenge REA faced was on measuring results. Given the scale of the programme, traveling to thousands of mini-grid and SHS sites to verify connections in person would be logistically infeasible and prohibitively costly. It would also be challenging for various verification agents to process information and documentation across numerous different on-site technologies to evaluate the service level of different households.

Odyssey’s collaboration with REA and the World Bank helped address both problems. Odyssey’s data platform acted as an integrator and enabled REA to analyse data coming from a range of different sources including mobile applications, live feeds from smart meters, SHS platforms, and more across varied organisations, technologies, and geographies.

For effective targeting and programme design, Odyssey’s platform was able to integrate a series of geo-tagged REA surveys, and a range of other datasets such as open-source geo-spatial data, to create a large dataset with insights on willingness to pay, availability of power, energy usage patterns, opportunities for productive use, and other key indicators. This data was directly integrated into Odyssey’s feasibility analytics platform, which generated relevant settlement-level demand forecasts, system design and financial modelling to determine the viability of different electrification pathways for each site. For verification, Odyssey remotely verifies connections for mini-grid and SHS customers by integrating with smart meter and SHS application programming interfaces (APIs) to collect customer payment and consumption data. This enables Odyssey to verify if energy access is provided to a customer and whether access is provided at specified reliability levels. Instead of having to verify these connections through individual visits, verification visits are now reduced to a small number of rapid audits allowing REA to rapidly disburse funds based on digitally verified results.

Figure 4: A snapshot of the data-management platform and dashboard hosted by Odyssey for REA

As Lande Abudu from REA stated for a recent piece for Odyssey: “Remote verification is providing a pivotal function for us at REA. It has significantly reduced the turnaround time for processing claims, speeding up the rate of disbursements. As a result, nearly seven million Nigerians have been impacted through the Output-Based Fund.”

As of March 2023, NEP provided new or improved electricity services to over 7.1 million people – well above the initial 2.5 million project target. The programme’s success is one of the key reasons the World Bank recently announced an additional $750 million in funding for NEP. The speed and scale of NEP highlights the potential for governments across LMICs to implement digitally enabled RBF programmes to make more rapid progress towards achieving inclusive energy access. For instance, the rural electrification agency in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is currently exploring opportunities for a digitally enabled RBF programme supported by the World Bank, which seeks to draw on lessons from previous programmes in Nigeria and Togo (read more about the role of data to support mini-grid site selection for the DRC programme in our recent piece).

NEP also highlights that digitally enabled RBF programmes can be a catalyst for broader market development and investment. The transparency and clarity provided through NEP and Odyssey’s data platform stimulated market entry and investment in Nigeria’s off-grid solar sector. It also opened up pathways for other innovative solutions such as Odyssey’s aggregated procurement platform. As Odyssey’s CEO, Emily McAteer highlights, demand aggregation and centralisation of procurement and logistics services can dramatically drive down prices for renewables equipment and accelerate deployment. Finally, Odyssey’s role in Nigeria also highlighted that clear alignment between technology provider (Odyssey), local government (REA) and funders (World Bank and AfDB) are critical to ensure the success of digitally enabled RBF approaches. As we highlighted previously, high-level alignment with government and political will is critical for the successful adoption of innovative data-driven processes in policymaking. Odyssey has just closed a $15 million Series A just seven months after raising a $5.3 million seed round last summer, highlighting tremendous market demand and need for effective data management platforms to launch, build, manage, and fund distributed renewable energy projects in LMICs.

Looking ahead

There is considerable potential for digital innovation to facilitate more effective design and implementation of RBF programmes across use cases beyond energy access. With the uptake of digital technologies such as digital payments to pay for rural water tariffs and sensors to monitor rural water pumps, there could be considerable potential for digitally enabled RBF programmes for rural water service provision. A pioneer in this is the Uptime Catalyst Facility, who issues non-repayable funding to rural water maintenance providers after results are confirmed. The Uptime Catalyst Facility recently announced a global expansion as it welcomes seven new service providers to results-based contracts aiming to serve four million people in 12 different countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America. It will be interesting to learn more about the role of digital technologies in the programme, and whether it will serve as a pioneering example for other RBF programmes in the sector.

Increased uptake of digital payment technologies mean that revenue records can progressively be verified remotely. Use of digital payments also has the added benefit of reducing collection costs for service providers (Uptime Catalyst 2021, Delivering Global Rural Water Services through Results-Based Contracts). Handpump monitoring technologies are still developing, and the costs for systems which are integrated sensing and data transmission capabilities still need to come down further for water service providers to be able to implement them and track infrastructure use at scale. As we’ve highlighted in our recent report, many IoT ecosystems in LMICs are growing rapidly but from a very nascent stage, and a lot of markets still do not have any deployed specialised networks.

As digital payment and IoT ecosystems continue to mature, the uptake of smart metering and PAYG solutions continues to grow, and the costs of key hardware and software inputs such as sensors and data management platforms continue to decrease, digitally enabled RBF programmes will become even more attractive across markets and use cases. To reap the benefits of these possibilities, donors and local governments must be open to innovate on processes and embrace digitalisation. Technology alone cannot build the coalition that makes the multi-stakeholder collaborations underpinning RBF programmes feasible, but it can help facilitate it. Ultimately, it is up to governments, donors, service providers and funders to understand that it is only through innovation that funding can be mobilised at the speed and scale necessary to meet the immense needs for essential service provision in LMICs.

We look forward to sharing further insights on digitally enabled RBF programmes in our upcoming report on digitally enabled innovative financing, which will be launched at MWC Africa. We hope to see you there!

The Digital Utilities programme is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), and supported by the GSMA and its members.