According to the GSMA 2017 State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money, Sub-Saharan Africa alone has 135 live mobile money services processing $19.9 billion transactions in value per year. The growth and increased sophistication of mobile money ecosystems across the globe has progressively allowed for the adoption of pay-as-you-go mobile utility bill payments in the energy, water, and sanitation sectors. Mobile utility bill payments benefit utility service providers and end-users by increasing payment transparency, reducing leakage, curbing operational cost, and providing avenues for financial inclusion. They also benefit mobile operators by helping to drive mobile money-adoption, average transaction value, and transaction frequency. For instance, in May 2015, Wonderkid received a grant from the GSMA Mobile for Development (M4D) Utilities Innovation Fund to deploy mobile tools including mobile payment solutions for four water utilities in Kenya. Between August, 2015 and December, 2016, the Kisumu Water and Sewerage Company, one of the water utilities supported by the project increased revenue collection by 28 per cent. Meanwhile, operators benefitted from an increased number of mobile money transactions to pay bills (71 per cent increase), and a 50 per cent increase in the value of these transactions over the same period.

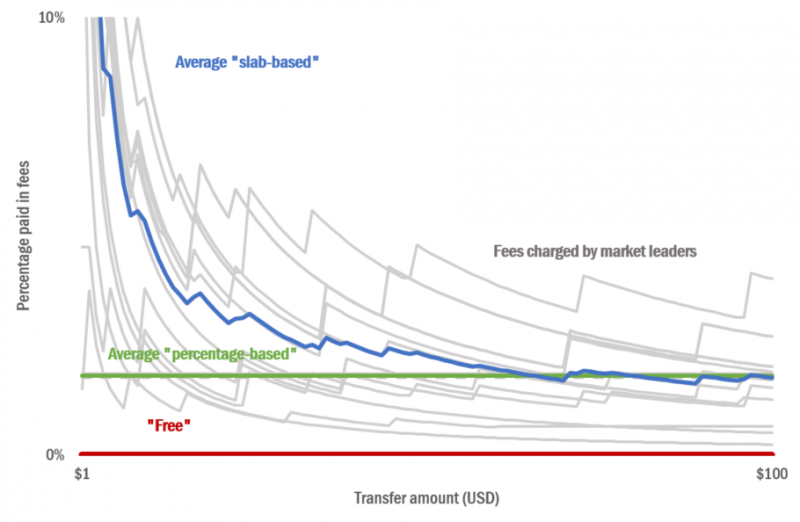

However, when mobile money transaction fees account for a significant proportion of the average end-user utility bill payment, it can be a significant barrier to widespread adoption. Generally, mobile money transaction fee pricing models can be broken down into three categories: “(1) slab-based pricing, where transactions within a predefined range are charged a flat fee; (2) percentage-based pricing, whereby the user pays a flat percentage of the amount sent, regardless of amount; and (3) free, with no transaction cost incurred by the user.” Slab-based pricing, the most wide-spread mobile money pricing model, is the most expensive one (on a percentage basis) for the smallest transactions.”

Though a slab-based pricing model is more user-friendly than a percentage-based model, especially among users with low levels of numeracy, it can also weaken the economic case for mobile money adoption in the context of pay-as-you-go utility payments, which are often characterised by small, but frequent transactions. This is particularly true in the context of first-time mobile money users and in nascent mobile money ecosystems, where fees are often interpreted as an insurmountable entry cost.

This has important implications for both utility service providers, and potentially, mobile operators. Rather than passing-on the entire cost of the transaction fee to the end-user, utility service providers could for instance consider whether there is a business case to absorb part of the transaction fee. For example, mobile operators might test if losses from a reduced transaction fee could be offset by higher mobile money penetration (especially in the long-run). Three of our GSMA M4D Utilities Innovation Fund grantees (and their mobile operator partners) addressed this through different innovative partnership models:

i) Introduction of a new tariff: CityTaps, in partnership with Société d’Exploitation des Eaux, a water utility in Niger, deployed smart meters that let subscribers pay for household water on a pay-as-you-go basis using mobile money. Given that CityTaps’ customers base is largely made up of low-income households, the company quickly realised that the lowest transaction fee charged by their mobile operator partner, Orange Niger (CFA 100 CFA, approximately $0.20) for payments between CFA 1001 to CFA 2000) was too high since the average value of individual household water payments was significantly below Orange Niger’s 1001 to 2000 CFA tariff. To address this, CityTaps successfully negotiated with Orange the introduction of a new tariff for transactions between CFA 500 and CFA 1,000 with a significantly lower transaction charge of CFA 50. Customers are now able to make smaller but more frequent payments without facing a disproportionally high transaction fee.

In certain contexts, mobile operators have already established special transaction fee categories to facilitate mobile money adoption for small merchants, utility bill payments, or businesses displaying a high social impact potential. For instance, in Kenya, Safaricom introduced M-Pesa Kadogo, a permanent tariff that scraps all transaction fees for both P2P and merchant transactions below Ksh 100 (approximately $1). Safaricom also reduced the lowest transaction value possible from Ksh 10 to Ksh 1 (the lowest monetary denomination in Kenya) to facilitate frequent micro-payments.

ii) Fee-absorption by the utility service provider: Safe Water Network (SWN) is improving access to water services by deploying mobile money services for pay-as-you-go household meters and water ATMs in rural Ghana. Similar to CityTaps, the majority of the SWN customer base are low-income users who pay for water in frequent micro payments. Given the immense revenue gains from introducing mobile payments, SWN decided to absorb the transaction fee in order to ensure widespread adoption.

iii) Fee-reduction by the mobile operator: Fenix International designs, manufactures and distributes ReadyPay Solar, a mobile payment-enabled solar panel, which empowers off-grid residents with affordable access to clean electricity. In this case, MTN Uganda’s decision to reduce transaction fees for ReadyPay Solar services not only facilitated the expansion of off-grid solar solutions, but also positively impacted MTN Uganda’s revenues. In 2014 alone, Fenix’s 13,000 customers conducted over 100,000 mobile money transactions, which made Fenix the third largest bill pay account by transactions for MTN Uganda. MTN Uganda also increased its customer base, as 13 per cent of ReadyPay Solar customers were previously not MTN Mobile Money customers.

As these cases exemplify, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all approach’. Crucial factors such as average utility bill payment value, mobile money penetration, and mobile operator pricing power are highly context-contingent. Despite this contextual diversity, the M4D Utilities programme recently held a mobile operator workshop in Kigali, Rwanda, to identify best practices for transaction charges in the context of utility bill payments through mobile money. Some take-aways included:

i) Operators identified the need to scrutinise transaction costs for utility bill payments given that they are a regularly occurring essential service; and

ii) Utility service providers are expected to clearly highlight the operator-business case for lowering mobile money transaction fees. Beyond obvious indicators such as a utility service’s ability to drive mobile money transaction frequency and value, this could also include a given service’s potential to scale, or its alignment with alternative mobile operator KPIs. (For more, please consult our Mobile Money Payment Toolkit).

In the public sector, several cities and municipalities are launching utility service payment platforms. In 2017, OR Tambo District Municipality in South Africa introduced the Thetha Nathi and Link platforms in partnership with Vodacom, which allow citizens to request, provide feedback, or pay for municipal utility services using a mobile application. Similarly, in Bangladesh, Practical Action received a grant from our M4D Utilities Innovation Fund to launch a mobile based water and sanitation related utility services platform, ‘1Service’, in partnership with Robi Axiata Ltd.

More wide-spread mobile utility bill payment adoption could also play an important role in achieving the mobile money industry’s stated aim of transitioning from a transaction-fee driven business model to a platform-based business model. WeChat’s successful app-within-app platform business model, which allows third parties to embed their content or their own functionalities through a mobile money platform, shows where the future of the platform payment industry could be headed. Given that utility use cases necessitate the collaboration of different actors across different ecosystems, they have to be recognised as a key enabler of moving to such a platform-based business model. Though utility bill payments already generate some revenue for MNOs, the growth of pay-as-you-go utility service provision (the pay-as-you-go solar industry is projected to reach over $6 -7 billion in annual revenues in 2022) , and smart meter applications (the global smart meter market is estimated to grow by 9.3 per cent annually from 2017 to 2022), highlight that utility bill payments can be even more substantial drivers of mobile operator revenue growth in the future.

For this potential to be realised, utility service providers and mobile operators have to continue to collaborate to find practical context-specific solutions.

This initiative is currently funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID), the Scaling Off-Grid Energy Grand Challenge for Development and

supported by the GSMA and its members.

By

By